Delft Design Guide 2.0 hits international book shelves

The completely revised and extended ‘Delft Design Guide’ is now on sale internationally. This design reference manual has been created for everyone that is - or aspires to be - a designer. Written and edited by Annemiek van Boeijen, Jaap Daalhuizen and Jelle Zijlstra, with contributions from more than 70 design researchers and practitioners, it has been created to help you to understand how a designer thinks, what a designer does and how this is done, the Delft way.

To celebrate the book’s second edition, we are bringing you this extract from the chapter on “How to use the Delft Design Guide” written by Associate Professor Jaap Daalhuizen and co-author, Professor Jeroen van der Erp:

What a designer does and how this is done, the Delft way

The diversity of perspectives and methodologies presented in the ‘Delft Design Guide’ shows that design is a rich field with many applications and a network of ways of working and tools to use. The ‘Delft Design Guide’ offers you a set of perspectives, models, approaches, and methods that serve four distinct purposes.

First, to help you to diverge or converge in your design project in a structured way, identifying and selecting options to solve your design challenges. Second, to help you determine what information and knowledge to find and use to allow you to make decisions and progress the design process. Third, to document and communicate a way of working that helps others to participate and collaborate with you. Finally, to develop yourself as a designer with a strong identity and rich toolbox to tackle the challenges ahead!

Build a mindset

The domains and application areas that design contributes to are becoming increasingly complex and turbulent. For example, designing interventions that help bring about positive change in the healthcare system – a very topical issue these days - is immensely complex and require skills, creativity and thoughtful actions, and productive collaboration. The content of the new ‘Delft Design Guide’ can help you in achieving impact, yet it is not enough on its own. Much of what is needed is embedded in the culture and values of this faculty, the missions of the design challenges we collectively work on, and can be identified in the principles of our way of working. In these we can see a strong common denominator that makes up the Delft designer. For example, we believe in being human-centric and evidence-based. We also believe in iteration and co-creation. Methodology provides the building blocks, yet you and the people working with design need to build a design mindset to bring these together into effective and meaningful ways of working. This is why we have added a section on mindset to each method in this new edition. These mindsets help you understand how and why a method can contribute to achieving a certain goal. Your first priority however, should always be to succeed in solving your design challenge and to have maximum impact for your cause.

Be reflective

We see design as a goal-directed discipline aimed at creating change. This is not a new idea: Nobel Laureate Herbert Simon already wrote in 1996 in his book The Sciences of the Artificial: ‘To design is to devise courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones’. Design is inherently uncertain and this can be traced back to the core elements in Simon’s definition. Designers explore new and sometimes untrodden territories when they ask: what would be a preferred situation? They discover and define opportunities for innovation and improvement. They ask what would be meaningful and valuable for people in their context and dare to take a stance to steer innovation. Designers challenge the way tasks or problems are framed and formulated when they ask what is problematic about the existing situation? They will keep asking questions until they find root causes and core values that form the starting point for good design. Designers facilitate and drive the development of design solutions that can realise the preferred situation when they ask: what courses of action will best realise the preferred situation and who should I involve to make it happen? They make ideas and visions tangible and iteratively explore their potential in realising the desired change. They will keep asking how to realise maximum effect with minimum means for people and within the complex systems that we find ourselves in today.

‘The Delft Design Guide’ embodies a diverse and rich set of perspectives, models, approaches and methods that can help you in navigating uncertainty and realising your design goals. There is one major prerequisite: you need to take the steering wheel and always reflect on what ways of working are most likely to help you achieve your goals. In doing so, you need to reflect on both your own values and beliefs as well as the ones of the organisation and community you are working with or for. This means that there are three core questions to ask yourself continuously:

- What do I want to achieve or contribute?

- What is the best way to reach these goals?

- Am I still on the best path to get where I need and want to be?

In short: be reflective!

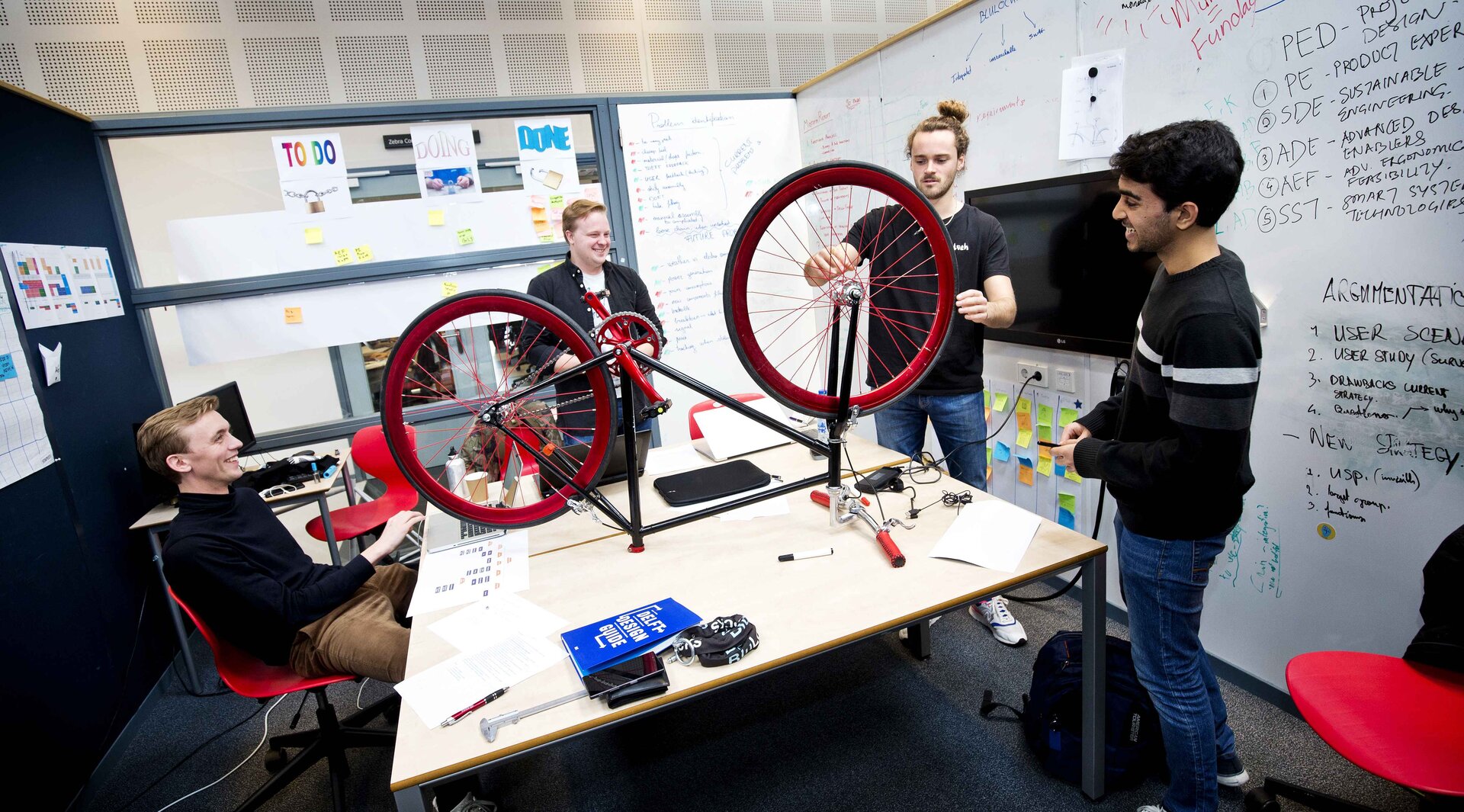

Be a co-creator and facilitator

Design is an integrative discipline. Designers work with clients, stakeholders in the organisation, external stakeholders, experts from other disciplines, users, et cetera. An important role of the perspectives, models, approaches and methods is to provide a common structure and language for innovation projects and practices that facilitate productive collaboration, trust and coordination amongst the diverse sets of people that are typically involved in design.

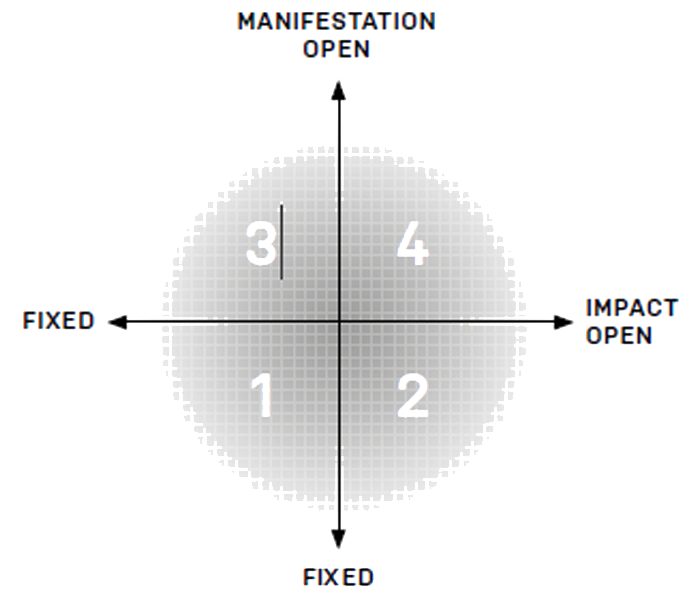

Be a navigator

A design assignment is typically framed along two dimensions: impact and manifestation. Impact refers to a desired effect of the design. Manifestation refers to the way the design manifests itself in the world, for instance, a physical product, a service, an app or a game. For both impact and manifestation, an assignment can either define what is expected, or leave it open for the designer. The position of an assignment in one of the quadrants gives direction to the kind of approach and/or methodology that is appropriate and likely to help you achieve your aims. Of course, the world is not as black and white as the matrix suggests, it should be used as a canvas. The more experienced you are as a designer, the more you know how to play with the model.

- Impact fixed, manifestation fixed. The classic design assignment: how the design should be manifested and what impact it should have is fixed. A good example is the assignment for a ticket vending machine for public transport. Both impact and manifestation are given from the start.

For this kind of assignment, you can work with a user-centred design approach to structure the overall process. Various methods like interviews or focus groups can be used to elicit and validate specific user needs. The WWWWWH method can be used to generate relevant questions for the problem analysis and a list of requirements to capture and manage all requirements to inform solution development. - Impact open, manifestation fixed. Assignments of this nature often focus on generating new business models or expanding current businesses. The manifestation in this case is often tied to the assets of the organisation, for instance, its current production facilities, technology expertise or distribution channels. A good example is TomTom, who became famous with its GPS navigation products. When smartphones were introduced, the company realised that selling hardware products to consumers would not be a sustainable business model anymore. Tom Tom successfully changed its strategy and moved from a business-to-consumer to a business-to-business approach, building on the available assets.

For this kind of assignment, you can work with the product innovation process to structure the overall process. Methods like SWOT and brand DNA can help to analyse and understand the current situation of the company. Methods like business modelling, and list of requirements to define the design brief and creative problem solving approach to develop and test solutions. - Impact fixed, manifestation open. Assignments like these often have a strong drive to realise change in a specific domain or situation. Hester Le Riche got her PhD in 2017 and developed the so-called Tovertafel (Magic Table). This is a device that creates ‘moments of happiness for people living with dementia and the people around them’. The assignment started with a clear aim to positively impact the lives of people suffering from dementia, yet the manifestation was not determined at that point.

- For this kind of assignment, you can work with a user-centred design approach, and use methods like contextmapping and observations as well as research to gain insight into the domain of interest. These insights can be synthesised using, for example, the Persona and Journey Mapping methods. Creativity methods like brainstorming or How-Tos can then be used to develop ideas, and storytelling and experience prototyping for testing and improving concepts.

- Impact open, manifestation open. An assignment in this quadrant often aims for exploring future possibilities in a domain, for instance, healthcare or mobility. There is a need to look beyond the current and to create a future vision. A good example is the Redesigning Psychiatry project. This is a consortium of companies and institutions that wanted to improve mental healthcare, with a horizon of 2030. Redesigning Psychiatry envision a future in which mental healthcare is no longer a rigid system but a dynamic network.

- For this kind of assignment, you can work with the Vision in Product Design approach to structure the work and explore and define a future direction in terms of impact and solution direction. Then, creativity methods like brainstorming or How-Tos can be used to develop ideas, alongside with storytelling and experience prototyping for testing and improving concepts.

The assignment journey

A design assignment will not stay stuck in a quadrant. As your project progresses, you move through the quadrants until you end up in quadrant one. For example, Boyan Slat started his quest with an open attitude, starting in quadrant three. As he progressed, he found out that 1000 rivers bring 80% of the plastic to the ocean. ‘Closing the tap’ - as he calls it - would heavily contribute to a more plastic free ocean. That led to the idea of the Interceptor moving his project into quadrant one. Sometimes an assignment has unclear or even conflicting aims, making it hard for you to determine where it is positioned. It is a good idea to ask questions and figure out with the relevant stakeholders what is really the aim!

Start-ups often ‘float around’ on this canvas. They often start with an insight, an idea or a hunch of how a certain technology can be brought to the market; manifestation rather clear, impact open. Yet, they might progress and find out that their initial idea for a manifestation was not the right one, flipping between quadrants two and three. They move back and forth between exploring user value and business opportunity. Once matured, they scale-up and stay in a single quadrant for a longer period.