Making a search plan

On this page

Why do you need a search plan?

What is a search plan?

Preparing for your search plan

Building your search plan

Type of information and resources to use

Trial and error

Additional ways of searching

Relevant links

References

When you start doing a research project, you should make a search plan for your information needs. A search plan makes you think about what exactly you are looking for and where you can find it. It helps you to search methodically and efficiently, and to find the best and most relevant information for your purposes. From this literature you can choose a key publication as starting point to search for additional information using the snowball method and citation searching. Bear in mind that searching for literature is an iterative process with “trial and error”.

Why do you need a search plan?

Before you start developing your innovative solution, you need useful information about, for example, types of technology, level of quality or effects on the environment. Searching for such information looks easy: just type some related terms in a search box and something will come up.

However:

- Is the information you found really relevant for your topic?

- Is the most recent information available?

- Are you sure that you haven’t missed anything important?

Making a search plan means that you will be able to answer “Yes” to all these questions.

What is a search plan?

A search plan consists of three parts:

- You first analyze your research topic.

Identify directive words that tell you what to do e.g. “discuss”, “compare”, “describe”.

Look for constraints, i.e. words that limit the scope of your assignment e.g. “during the last ten years”, “in the Netherlands”.

Determine the concepts e.g. the aspects that describe the subject of your assignment. - You then formulate your search queries.

- And finally, you determine what type of information you need (theoretical background information; state-of-the-art research results; standards and regulations; current affairs; etc.), and where you could conceivably find that type of information.

Preparing for your search plan

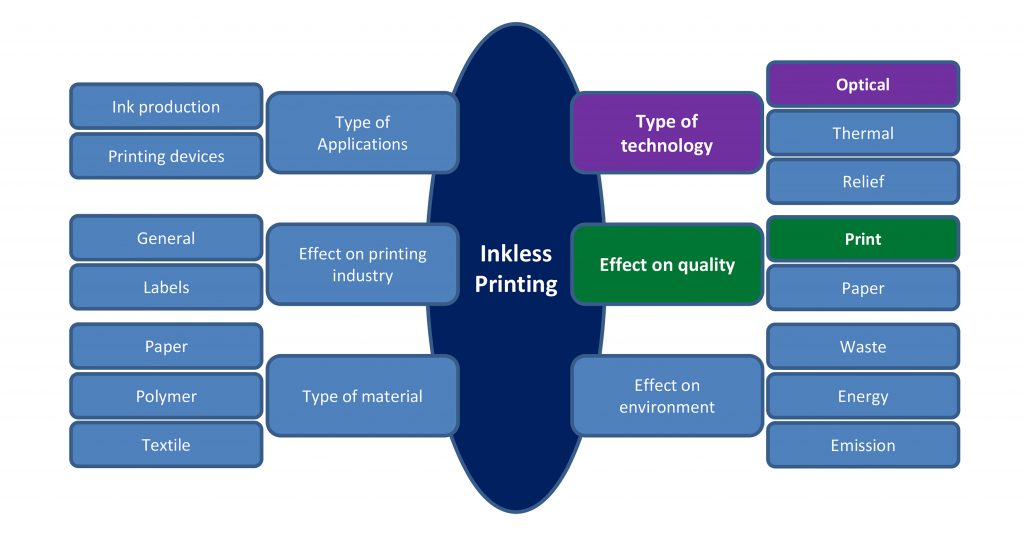

To create a search plan you will need a research topic. To determine your exact research topic, you can start with a general orientation on the subject you are interested in for instance “inkless printing”.

- Think of relevant concepts that are related to your subject and perform general searches in Google, Wikipedia or dictionary to find useful terms. If you want to search anonymously on the internet you can use alternative search engines like DuckDuckGo (data from more than 50 search engines, does not store IP addresses and search data), Startpage (does give Google results, but also serves as a proxy -wall- between you and Google) and Gibiru (search results are sourced by a modified Google algorithm).

- A next step can be to search in a multidisciplinary database like Scopus or Web of Science and in subject-specific catalogues or databases for your research field. Check the titles, abstracts and keywords of documents you find useful.

The reliability of multidisciplinary databases such as Scopus and Web of Science is guaranteed. If you don’t want to miss particular information it is also important to search in subject-specific databases. The quality of these databases may depend on the subject area.

It is important to know that when a topic is in the spotlight a lot is written about it and a search will give you a lot of results in contrast to a less popular topic. - Process any interesting terms you come across in lists or a concept map.

Research topic

A subject like inkless printing has many topics to be researched, so you need to determine which topic(s) you need to research.

A good research topic should be:

- specific: it clearly describes what you will and what you won’t be researching

- socially relevant: useful to a certain target group

In order to formulate a specific research topic, you can, for example, use a concept map.

Making a concept map from the information you have available gives you a clearer overview of your subject. You can then use the concept map to formulate various research questions. You formulate research questions by looking at the relations and dependencies of different branches of the concept map.

From this concept map we have formulated the following research question:

“How can the print quality of inkless printing be improved by using optical technology?”

Another possible research question could be:

“How does inkless printing by optical technology influence the energy consumption of the printing industry?”

View this video about concept mapping:

Sub-questions

In order to answer the research question “How can the print quality of inkless printing be improved by using optical technology?”, you should formulate a number of sub-questions. When you have answered all the sub-questions, you will also have a complete solution for your research topic.

- A research topic can consist of multiple terms. The ‘What’ and ‘How’ sub-questions can therefore be posed multiple times.

- Very often, you won’t be able to answer all five types of sub-questions. The ‘What’ and ‘How” sub-questions must always be posed, but the social relevance questions depend on how specific your research topic is.

| Question | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| What? | Definitions of terms |

|

| How? | Relations between terms |

|

Why?

Where? | Social relevance: target group geographical demarcation |

|

Building your search plan

Analyse your research topic or sub-questions

Most research topics or sub-questions can be split into separate concepts. Eventually, you want all concepts to show up in your search results, but in a search plan you should first search for the concepts one by one. Take a look at these examples of research topics and their corresponding concepts.

Research topic | Concepts |

|---|---|

| How can the print quality of inkless printing be improved by using optical technology?” | Inkless printing |

| Print quality | |

| Optical technology |

For each concept, try to think of different terms that other people might have used to describe it. Think of alternative search terms: more general terms, more specific terms, different word endings or related terms.

List your concepts and all alternative search terms for your concepts in a search table to complete the first step of your search plan.

| Combine the concepts with AND | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Combine the synonyms with OR | inkless printing | print quality | optical technology |

| inkless print* | print* quality | optic* technolog* | |

| ink?free print* | lasting print* | optic* | |

| print* without ink | permanent print* | laser* | |

| thermal print* | durability | thermal* | |

| heat-induced print* | durable | lenses | |

| permanent print | high resolution | carbonisation* | |

| high contrast | carboni* paper | ||

Explanatory note:

- Concepts and synonyms / related terms are in English, because most search systems (resources) are in English.

- An asterisk (*) replaces 0 or more characters; this is called truncation

- A question mark (?) replaces 0-1 character

Formulate your search queries

First formulate a search query for each of the columns in your search table. Combine all search terms in the column with the operator OR to find as much information as possible.

Then combine these search queries with the operator AND to limit your total number of results and make them more relevant.

| Search query 1 | “inkless print*” OR “ink?free print*” OR “print* without ink” OR “thermal print*” OR “heat-induced print*” |

|---|---|

| Search query 2 | “print quality” OR “lasting print” OR “permanent print” OR “durability” OR “durable” OR “high resolution” OR “high contrast” |

| Search query 3 | “optic*technolog*” OR “optic*” OR “laser*” OR “thermal*” OR “lenses” OR “carbonisation*” OR “carboni* paper” |

| Search query 4 | [search query 1] AND [search query 2] AND [search query 3] |

In many search systems you can combine queries without having to retype them. You can tick the queries in your search history and click on “combine”, or sometimes you can refer to the queries by their number in your search history and combine them by typing, for example: #1 AND #2 AND #3.

(“inkless print*” OR “ink?free print*” OR “print* without ink” OR “thermal

print*” OR “heat-induced print*”) AND (“print quality” OR “lasting print” OR

“durability” OR “durable” OR “high resolution” OR “high contrast”) AND

(“optic*technolog*” OR “optic*” OR “laser*” OR “thermal*” OR “lenses”

OR “carbonisation*” OR “carboni* paper”)

Tip: Depending on the source you may not be able to use all search operators or, for example, combine sets. Please refer to the help section of the source to construct a correct working search query.

See also: Search operators

Type of information and resources to use

What kind of information are you looking for? Check the table to determine which document type you need and where you can find it.

| Type of information | Type of document | Where to find it |

|---|---|---|

| Background or introductory information |

|

|

| Scientific information and current research results |

|

|

| Technical information |

|

|

| Public opinion |

|

|

| Factual information |

|

|

See also: Resources

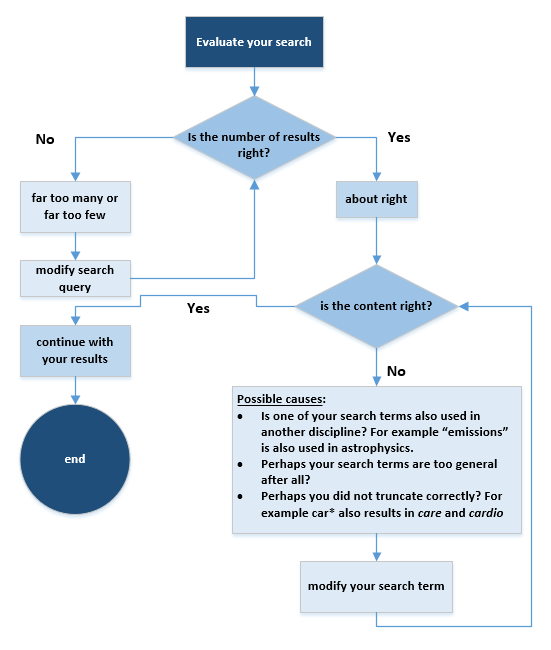

Trial and error

Searching is a matter of trial and error, and you do not create a perfect search plan all at once. You create a search plan, try it out, evaluate your search results, edit your search plan, and keep repeating these steps until your search plan is the best you can make it.

If you have found far too many results, you can sort your results by relevance (Scopus). Relevance means that the results of your search are of significance for your research topic. Look at the title and abstracts of the documents you found and if less than 50% of the documents is relevant, adjust your search terms. For relevant search terms you can also use keywords assigned by the database itself.

In a proper literature search about 80% of your search results should be relevant. If all the documents you found are relevant then you should ask yourself if you don’t miss important literature and therefore should broaden your search.

Tip: If you need to be complete don’t forget that databases do not always contain the most recently published articles, because there can be a delay of up to 6 months between the publication of an article in a journal and its inclusion in a database. Therefore it is advised to check the table of contents of the most important journals in your field.

For more information about the relevance of your search results, go to: Evaluating search results.

Tip: If you are really satisfied with your search query, save it and create an alert in order to receive a message when a new article is available. For more information, go to: Setting up alerts.

Additional ways of searching

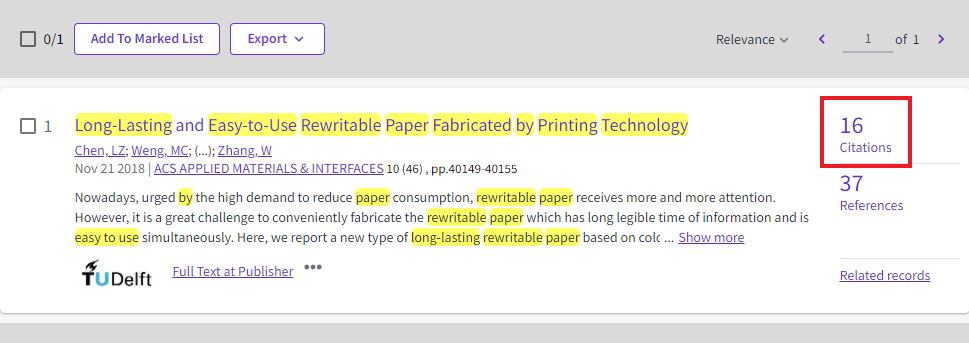

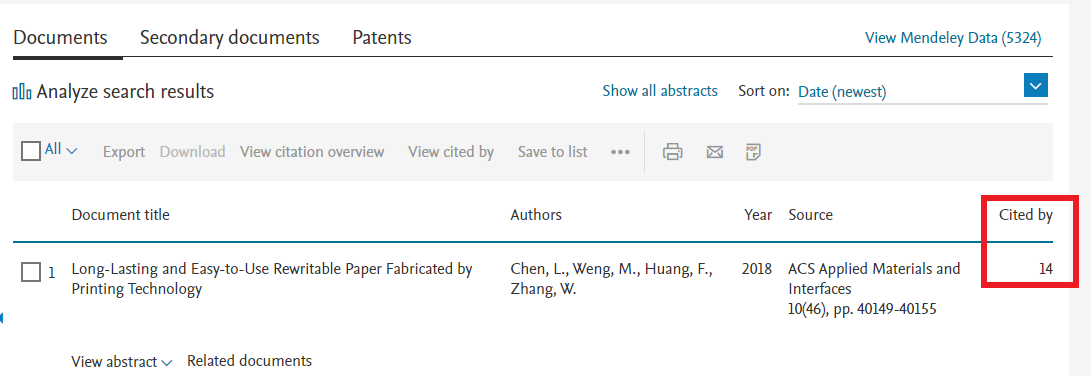

When you have found relevant literature by using your search plan, it can often be useful to look for more sources. Check out two additional ways of searching by taking a key publication (some subject areas have access to a “reference or source publication” or your teacher draws your attention to an important publication) as starting point: snowball method and citation searching. In some cases it is possible to start with a “review article”, which might give you an extensive reference list.

Snowball method

Take a key publication and search for additional information or related topics. You can, for example, look for publications by the same author or search by keywords found in that publication. By looking up the references of that publication you can also find new relevant information for your topic.

Citation searching

Take a key publication and look up the papers that are citing this publication. That way you can find out how other authors have used or built upon the information from the key publication.

Two examples where to look for information about citations:

Relevant links

A-Z list of journals titles

Sources by faculty discipline

Concept mapping for Developing your Research

Choosing a Manageable Research Topic

References

Stewart, C. (2018, February 8). The best private search engines: alternatives to Google. https://hackernoon.com/untraceable-search-engines-alternatives-to-google-811b09d5a873