Why doesn't it work and can it be fixed?

Everyday annoyances: the hoover that suddenly stops working, the washing machine that refuses to spin. Or, a small disaster for the at-home worker, the coffee machine that refuses to give you fuel. And yes, of course you can order a new one, but if you want to contribute to a circular economy, you might also want to see if there is anything that can be repaired. PhD researcher Beatriz Pozo Arcos studied how easily defects in household appliances can be diagnosed, and how design can help users do this.

Why is there no coffee?

In the Product Evaluation Lab (PEL) at TU Delft, we see a man sitting with a coffee machine. The machine’s on/off switch shows a dangerous blinking red light. You can almost feel his frustration: there goes his nice cup of coffee. Next to the man is a tray with screwdrivers. An employee sits further down and writes. The man can get straight to work.

Broken appliances in the home reveal a lot about the personality of their owner. For some, they arouse anger and frustration, so-called 'technology-related anger', for others resignation, and for some the urge to repair the defect. How does the coffee machine man figure out why the light is blinking? Or why there is no coffee coming out of the machine? PhD student Beatriz Pozo Arcos set out to research this and more.

How design impacts device repair

Pozo Arcos conducted the first part of her research on an internet forum called iFixit. There, users help each other repair devices. It gave her interesting insight into the way the average user operates when something breaks down at home. How does a person determine what is wrong, what options are involved in the assessment, and how does the user check which of these options they need? Pozo Arcos concentrated on these questions, in addition to advice about blenders, hoovers, and refrigerators. Her observations provided her with an initial framework for the steps users follow when an appliance breaks down. And from this she saw how the design of an appliance affected those steps.

How do people identify defects?

She then had users work on household appliances in the Product Evaluation Lab, the users included both experienced handymen and people with two left hands. This way, she and her colleagues could observe how people detected, located, and isolated the defect. She also saw whether the design of a device helped them or not. She asked the test subjects to think aloud about the steps they had to take, so that she could follow along closely with the steps they considered when identifying the defect. Remarkably, our senses play a major role in detecting defects. Did the hoover make a strange humming noise? And where did that smell of fire come from?

In the lab, the test subjects were given clues by a researcher if they could not make progress. Pozo Arcos noticed that many people gave up quickly. Through the offering of advice, she also gained insights such as: What did people do with it? Did it help them? Did they manage to find out what was wrong with the device in the 40 minutes they were given? It was not a question of whether they succeeded, but how they approached it. The cautious conclusion: many devices are too complex to be able to determine what is wrong when they malfunction.

Manuals, manuals, and more manuals!

And then, of course, we come to step three of research: the user manual. For her dissertation, Pozo Arcos studied no fewer than 150 instruction manuals from 15 brands, for various household appliances. It turned out that for many defects, the instruction manual does not offer a conclusive answer. A clogged washing machine filter? The instructions explain what to do. But it says nothing about a malfunctioning motor.

Advice for manufacturers and designers

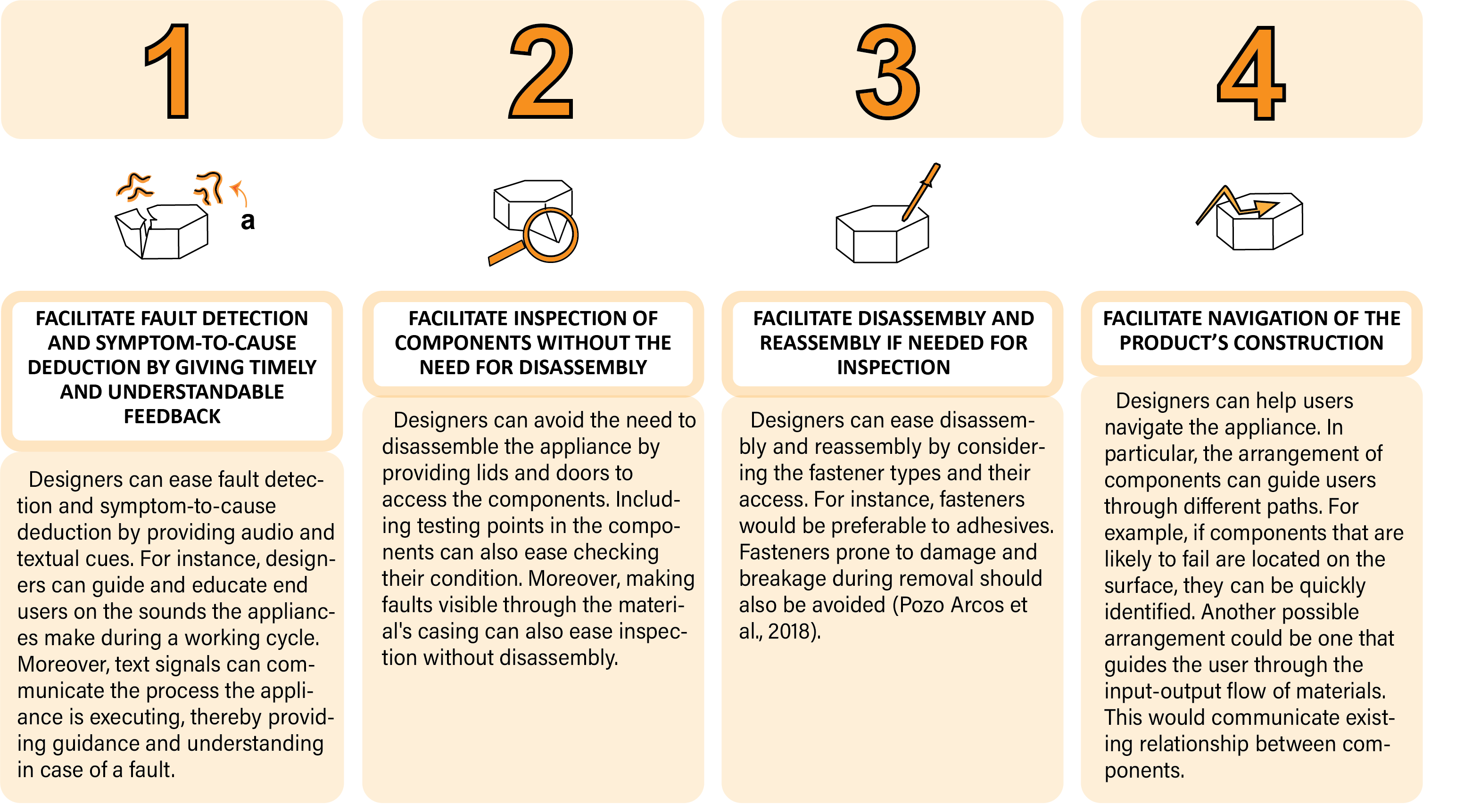

In her dissertation Pozo Arcos makes recommendations such as: it must be easier to detect what is broken. Furthermore, it is an good idea if you do not have to dismantle a device to see what is wrong or if, for example, it has doors to check the various components. And if you do have to dismantle a device, it's easiest if you can put it back together in one go.

Incidentally, Beatriz Pozo Arcos herself does not shy away from repairs. She even worked as a volunteer at the Repair Café in her former home town of Rotterdam, just for fun. Her speciality? Record players. “I always appreciate it when something can be repaired. Then I don't have to throw it away.”

Conny Bakker

- +31 (0)15 27 89822

- C.A.Bakker@tudelft.nl

-

Room B-3-330

Ruud Balkenende

- +31 15 27 81658

- a.r.balkenende@tudelft.nl

-

Room B-3-310