NL / EN

The faculty of Industrial Design Engineering at Delft University of Technology was founded in the 1960s with modest means, a few lecturers and two students. It has since grown into an international teaching and research institution. Over the years, fierce debates took place about different approaches to design education, the staff developed all kinds of scientific research programmes and the faculty moved from a small attic, by way of various locations, to a large building of its own at the heart of the TU Delft campus. Read all about 50 years of teaching and research on design, and the people who were involved in this.

The economic disarray that prevailed after the Second World War spurred the Dutch government to formulate an industrial policy. This naturally included a new kind of education on design. For the time being, the response from the Delft Institute of Technology was a cautious one.

Industrial design

At the request of the Minister of Education, Science and the Arts, several artistic and sometimes also radical progressive designers, including Mart Stam and Andries Copier, drew up plans for a programme to train industrial designers. This plan was supported by the minister in an economic-organisational sense, although not ideologically, and was subsequently presented to the Institute of Technology in Delft.

Since the government’s first initiatives, however, the faculties of Mechanical Engineering and Architecture had had serious objections. Mechanical Engineering was concerned about artistic influence on technical education, whereas Architecture had an opponent to the new industrial future in the person of the architect M.J. Granpré Molière, who took his inspiration from religion. There were also proponents of ‘industrial design’, however, such as the traditionalist professor Frits Eschauzier, who specialised in interior design, and the modernist professor of architecture Jo van den Broek.

Joost van der Grinten

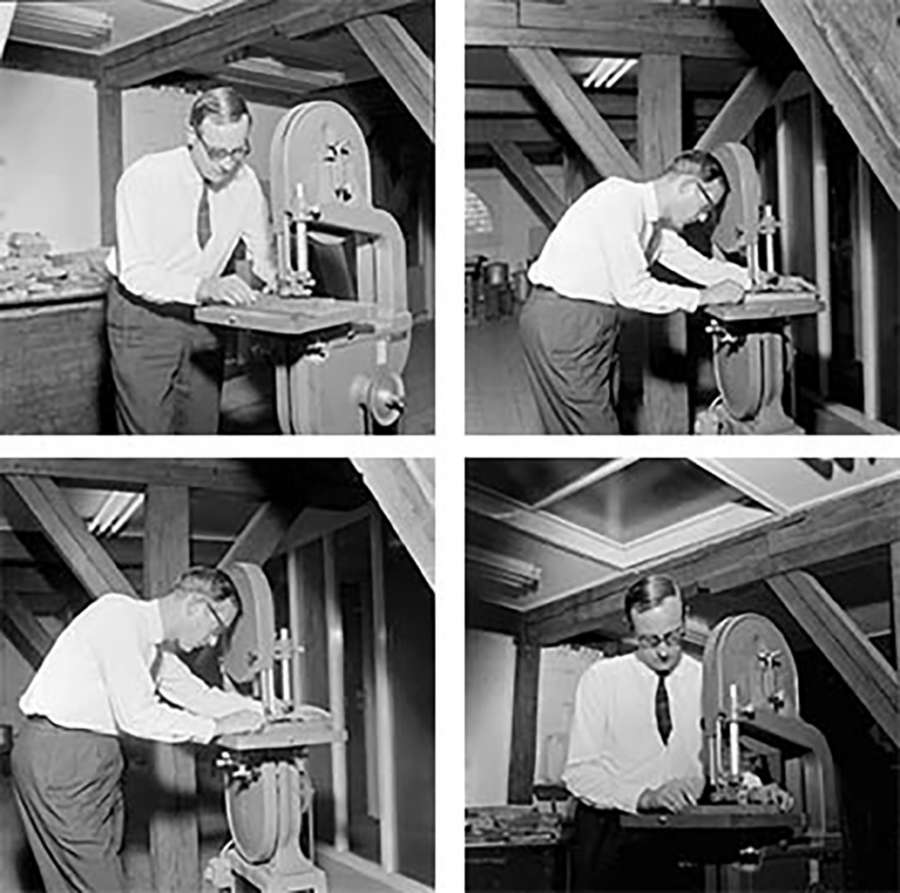

Frits Eschauzier had close ties with Philips, whose head of design, Louis Kalff, had himself trained as an architect in Delft in the 1920s. Kalff and the young Philips designer Rein Veersema had given a number of lectures on product design in Delft in the 1950s, enabling students to become acquainted with the new field. A promising architectural trainee at Philips, Joost van der Grinten, would eventually develop the new degree course in Industrial Design.

Playing catch-up

Van der Grinten was familiar with the academic world and practice, the latter not only due to his short period at Philips, but also due to the family business, Van der Grinten, which manufactured photocopiers. When working as an assistant to Eschauzier, he had made a study of the various design courses in Europe, such as those at the Royal College of Art in London and the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm. His conclusion was that the Netherlands was behind the times in training modern designers, and that the country had to make good speed to catch up. His advice was not initially heeded, but after the intervention of several professors and at the insistence of a board member of the Institute of Technology, Kees van der Leeuw (the director of the famous Van Nelle factory), the young and energetic Van der Grinten was given a new chair, followed in 1962 by his appointment as an endowed professor.

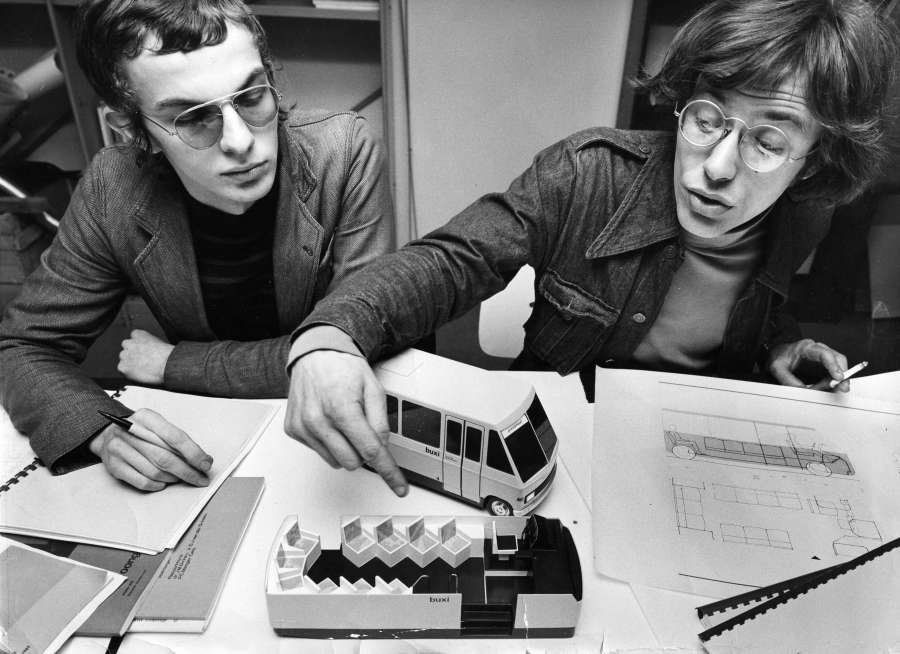

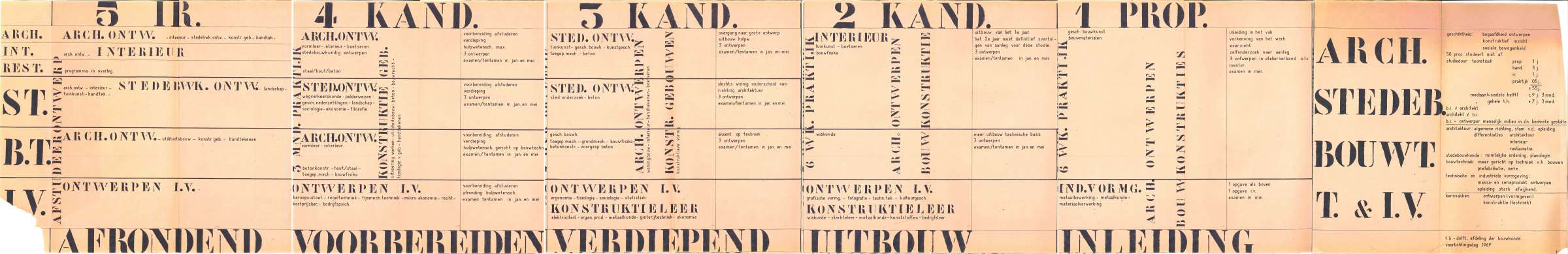

With his appointment as an endowed professor in 1962, Joost van der Grinten had in fact assumed responsibility for setting up a new degree programme in industrial design. For the time being, this took the form of a degree programme within the Architecture faculty, which was run alongside Interior Design, Construction Techniques and, of course, Architecture. The main research group was known as Technical and Industrial Design.

The Architecture faculty’s curriculum stated emphatically that the new degree programme had an entirely individual character. This characterisation may have reflected many architects’ lack of affinity with this new field, but even more so, it was consistent with the rigorously independent approach that Van der Grinten and his new staff managed to develop.

The ideas for the degree programme steered clear of debates on modern architecture and were in keeping with the analytical approach taken by technical engineers, with their knowledge of production techniques and qualities relating to product use.

Van der Grinten found design practitioners to staff the new degree programme, notably with different approaches and contrasting views. From 1964, the designer Emile Truijen played an important role in developing the teaching on design. Truijen had been introduced to commercial design practice in the United States, and in 1954 he had been one of the first to set up a design agency in the Netherlands (with Rob Parry). In 1965, Van der Grinten also invited the leading graphic designer Wim Crouwel, who had already developed his analytical approach at his design agency, Total Design. The first full-time professor was the mechanical engineer Bernd Schierbeek, who had previously been head of product development at the international manufacturer of weighing scales and cutting machines, Van Berkel.

On 7 February 1969, the Institute of Technology received ministerial approval for the new degree programme in Industrial Design. In the following years the first graduates came through, most of them having been supervised by Bernd Schierbeek.

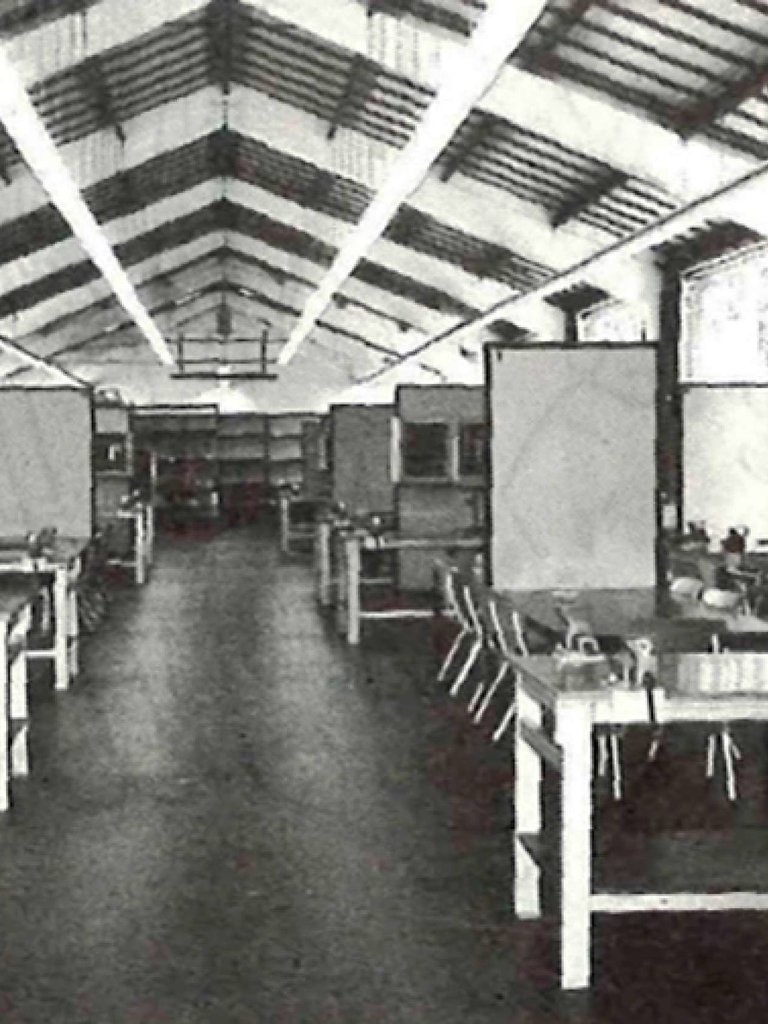

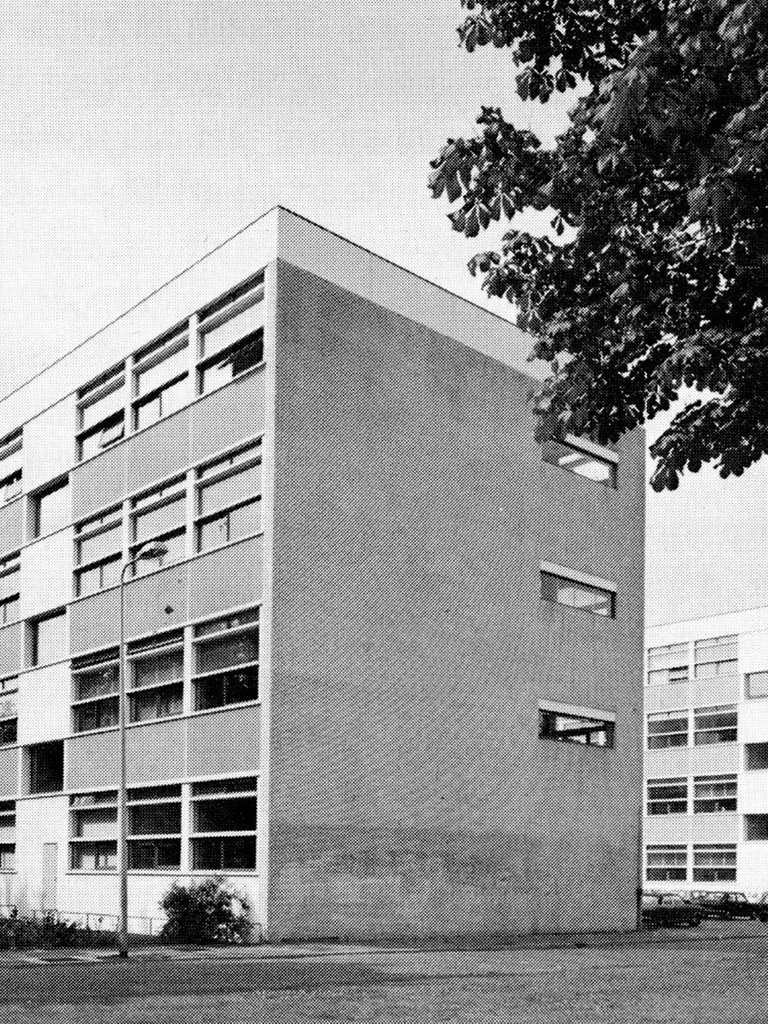

On 7 February 1969, the Institute of Technology received ministerial approval for the new degree programme in Industrial Design. Independence had immediate consequences, and the number of applications to the programme rose sharply. In 1971 the faculty acquired another building, this time on the Ezelsveldlaan. It was here that the number of first-year students taking the programme would reach fifty for the first time, and it was also here that the first engineer of Industrial Design (ID), Norbert Roozenburg, graduated.

Professor Truijen’s young staff made a self-confident start on a new plan for the degree programme, which would be put into operation in 1971 as the “Boerakkerplan”. The core of the new plan comprised design exercises, supported by problem-analytical research. This approach was derived from the book entitled ‘Structure of Design Processes’ by the celebrated British design theorist, Bruce Archer.

Although the association with Architecture was still new, the degree programme in ID quickly developed a very different character

In the same year, the programme officially became independent and continued as a Bridging Department, now on the Ezelsveldlaan. Although the association with Architecture was still new, the degree in ID programme quickly developed a very different character. After all, product design involved massive differences in scale, manufacturing methods, types of use and thereby also a different debate. At this time, the Bridging Department was recruiting practitioners such as the graphic designer Wim Crouwel (1972) and the product designers Aat Marinissen (1971), Wim Groeneboom and Wim Rietveld (1973).

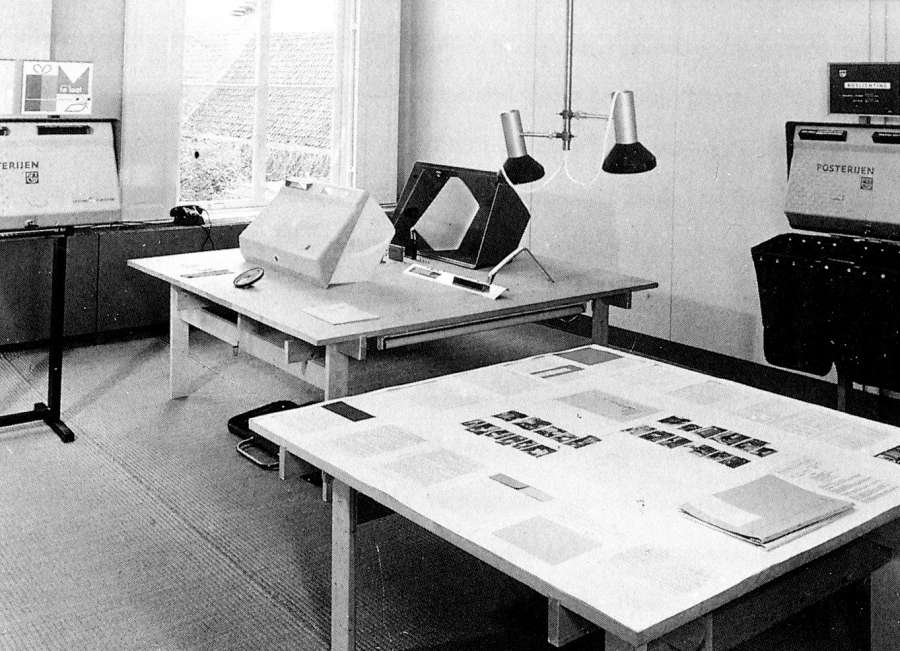

With the focus on product manufacturing and use also came a very different kind of research tradition from that which prevailed in architecture. In short, the greatest difference lay in the amount of attention paid to the relationship between products and people. With respect to this, the Leiden-based psychologist Hans Dirken was appointed to teach ergonomics (1972), and the Groningen-based historian Henri Baudet was given a lectureship that focused not so much on the cultural history of design, but on the social and economic aspects of the use of products. The first research carried out within the degree programme concerned the typological development of the telephone apparatus, a research theme that was to feature in the degree programme for a long time.

The year 1979 saw the graduation of the one-hundredth engineer in Industrial Design. During the 1970s, it had gradually become clear that the new, independent degree programme would continue to grow substantially. Great interest from students and from the private sector led to the appointment of new lecturers and professors. A socially engaged conception of design prevailed among the staff and the students. In the course of the 1980s, these ideological principles would slowly be cast off.

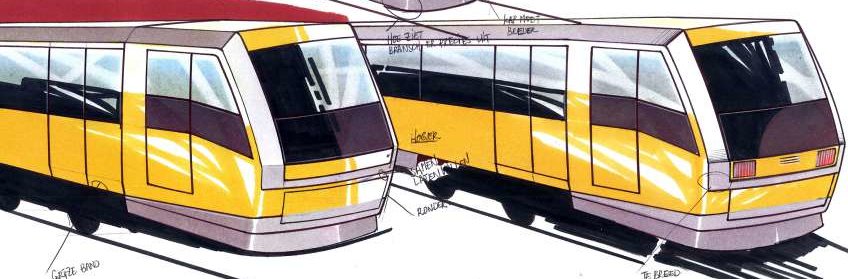

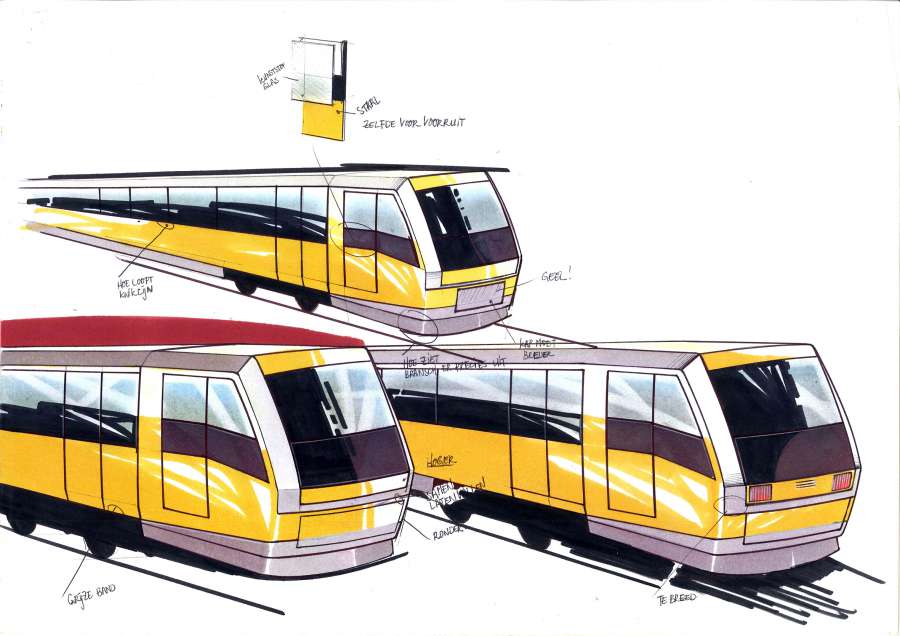

The department of Industrial Design grew rapidly at the end of the 1970s. The atmosphere among the staff members, most of whom were young, was downright dynamic, with an ideological struggle taking place on the principles of design. Many of the staff wanted a degree programme focused on commercial design practice. Others propagated the idea of the designer who would contribute to creating a better society, aided by modern technology. There were also groups of students who blatantly rejected both the high-tech route and the notion of contributing to a consumer society. Rather than doing their graduate projects at private companies, they preferred state enterprises such as PTT and Dutch Railways, although this dismissive attitude began to change in the course of the 1980s.

These different conceptions of design did not hinder the further professionalisation of the degree programme. In 1978, Industrial Design was split definitively into four. Technology (later Construction), Product Ergonomics, Design and Business Administration were already the research groups that represented the ‘specialities that are needed to produce an industrial product.” Gerard van Eijk was made the first professor of Business Administration at Industrial Design. The considerable size and growing prestige of the degree programme were reflected in the appointment of Professor Hans Dirken as rector magnificus of the Institute of Technology. The department’s growth was also reflected in its housing: in 1978, the faculty moved to a building on the Jaffalaan, while on the Drebbelweg a couple of large drawing halls at Shipbuilding were converted for design-related supervision.

With the development of different schools of thought, attention was increasingly paid to studying design in a scientifically robust way. Understandably, the dominant view of design had originated from engineering analyses, supplemented with knowledge from various fields. Scientific interest within the faculty, however, mainly developed from the social and life sciences. In design methodology, for example, there were attempts to use models to understand the specific thinking and actions of the designer. In the 1980s this school would grow considerably, and the presence of scientists such as Nigel Cross, Norbert Roozenburg and Willem Muller would ensure the international reputation of Delft’s integral scientific design programme.

Developing the science did not mean that design practice disappeared into the background. To a much greater extent than in other Delft programmes, most young engineers carried out their graduation project at a company or institution.

The faculty recruited quite a few lecturers from companies such as Philips and Van Berkel; they included Wim Groeneboom and Aat Marinissen, for example. During this period, the faculty also had a number of prominent representatives from practice in its midst. Ootje Oxenaar was known for his world-famous designs for Dutch bank notes and in 1978 became special professor for Visual Transfer and Presentation, while the graphic designer Wim Crouwel was appointed professor of Industrial Design in 1980.

The original aim of making Industrial Design a broadly oriented degree programme was finally achieved during the 1990s. More so, the aim became one of producing integral design engineers; that is to say, engineers with an understanding of the technical, commercial, ergonomic and design-related aspects of product design.

On the one hand, the various specialisations of the faculty of Industrial Design meant a deepening of research and teaching. On the other, the broad scope failed to fully achieve the old ideal of an integral approach to design. The all-rounder who, to a certain extent, matched his studies to his preferences and talents turned out to be the same ideal type that had once also been sought in design itself, but only rarely found. From 1994 onwards, students had to make two important choices during their studies: a choice between product development and innovation management in the course of the third year, followed by a choice between practice and research.

Partly due to the steadily growing student numbers, the departments were able to appoint more lecturers and professors. This resulted in specialised research programmes. From the 1980s, for example, a considerable amount of attention was paid to product sustainability, thanks to the appointment of Han Brezet and later Ab Stevels as professors in this area. Almost as a counterweight to functional thinking on engineering and the impact of mechanical engineering on the programme’s profile in the initial years, interest also developed in the working of semantics, which was investigated by the psychologist Gerda Smets and her research group.

The growth and notable success of Industrial Design led to several far-reaching reorganisations. In 1999 the old, four-part ‘clover-shaped’ model was replaced by a three-department structure. At the university level, too, the Executive Board was pushing for simplification and amalgamations. From 1997, a merger was pushed through with the cash-strapped faculty of Mechanical Engineering, creating the large faculty of Design, Construction and Production (OCP). This merger was reversed in 2004, however, as it had hardly produced any collaboration. The faculty of Industrial Design then became independent again.

This broad approach, combined with the many opportunities within the degree programme and the ambition to train all-round design engineers, attracted significant international interest during this period. What had begun in Van der Grinten’s time as a catch-up effort to prevent the Netherlands from falling behind now seemed to have been transformed into a head start, reflected in great interest from and sometimes imitation by foreign institutions. By this time, the school had existed for two decades and had built up a network of self-trained design engineers who had enjoyed careers in commercial practice and other expert institutions. In 1986, two of them would return as professors: the young professor of Management and Organisation of Product Development Jan Buijs came from TNO, and the professor of Industrial Design Jan Jacobs had been chief designer at Gispen, the office furniture manufacturer.

With its regained independence, it seemed that the faculty had to reinvent itself. A new building, a new curriculum and new perspectives on design characterised the years after 2004.

The organisation prepared for a move to what many considered to be a colossal building on the Landbergstraat. The curriculum was also revised radically, in several phases. First of all, the old Bachelor’s programme was tackled in an all-out attempt to offer a range of divergent subjects and disciplines in an integrated programme. Three new Master’s programmes were introduced in 2006, which both reflected the old disciplines and even the research groups and captured new developments. These English-taught Master’s were Design for Interaction (Dfl), Integrated Product Design (IPD) and Strategic Product Design (SPD). Healthcare remained a separate and succesful specialisation.

The faculty’s new building was a converted workplace, meaning that the faculty had an impressive and multifunctional entrance hall at its disposal. The hall was eventually equipped with comfortable workplaces, and tables and laptops took the place of the workbenches where first-year students had diligently sawed and filed away. The hall also functioned as a venue for large events. Each year, the diverse population of the Construction Faculty proved an irresistible draw for other Delft students during various celebrations.

The adaption of the hall was symbolic of the changes that had been made to education at the faculty of Industrial Design. The degree programme had once begun with a single professor and an enthusiastic staff of practitioners, mostly with technical backgrounds. From 2000, the faculty increasingly managed to carve out a clear place for itself in the international scientific world. A rapid rise in the number of theoretical insights was combined with ideas about the designer who had not so much knowledge of the design and technological aspects of a product, but more the ability to assess what should be made and how the new design would function in society.

After 2000, a new generation of professors would investigate new directions in design. With professors such as Jan Schoormans and Eric Jan Hultink, the department of Marketing and Innovation Management grew and contributed to market-oriented product development. Researchers on semantics developed ideas on design and experience and on design in a social-cultural context. These ideas were successfully applied in teaching and research by the research groups led by Paul Hekkert and later by Pieter Desmet and Pieter Jan Stappers.

The continuous growth of the faculty made both our student and our scientist population ever more international. With the shift from product to product/service-systems due to the pace of technological developments and social challenges, designers operate in an increasingly complex world. Coming technological revolutions such as the Internet of Things, biomaterial additive manufacturing and artificial intelligence also bring a renewed focus on people and organisations. A prime example of this is ethics in design: in 2017 IDE alumna Jet Gispen was elected Best Graduate of TU Delft. She developed an ethics toolkit for the design practice.