Training for surgery? Get (more) real

The field of general surgery has been transformed over the past few decades with the rise of minimal access surgery (MAS), making it possible to perform major surgeries via small incisions. But as with any rapidly developing technology, there are often challenges related to training and implementation. Through his PhD research, Sandeep Ganni set out to explore the key elements required for designing safer and more effective training methods related to MAS.

Looking at how surgeons learn

It’s no surprise that Ganni chose to pursue studies in a field related to medicine. His father, a surgeon, founded GSL Medical College in India about 20 years ago to train people for various medical careers. It was there that he met his future promoter, TU Delft Professor Jack Jakimowicz, whom they had invited to give a lecture on virtual reality-based education for surgeons. At the time, Ganni was in charge of setting up a new skills lab at the college. “We got to talking and thought we should do a project together to see where this technology is going and how it’s affecting surgeons,” he said. “That’s what brought me to the Netherlands.”

Traditional apprenticeship training methods can take upwards of three years before a surgeon actually lays hands on a patient. Initially, Ganni intended to research the efficacy of new immersive training methods like virtual reality to see if such technologies reduce learning time and improve patient safety. But he soon realised that in this rapidly emerging field there are more technologies than surgeons can cope with and they are constantly changing. So, what he thought would be purely technical and qualitative research evolved to into a stronger focus on design.

Make it personal

Through his evaluation of simulation-based training, Ganni proposed taking a more tailored, personal approach. “Where human-centred design comes in is designing for the surgeon rather than designing something else and asking the surgeon to cope with it,” he said. Through the course of his research, he worked with over 300 surgeons, including his own father, in different countries.

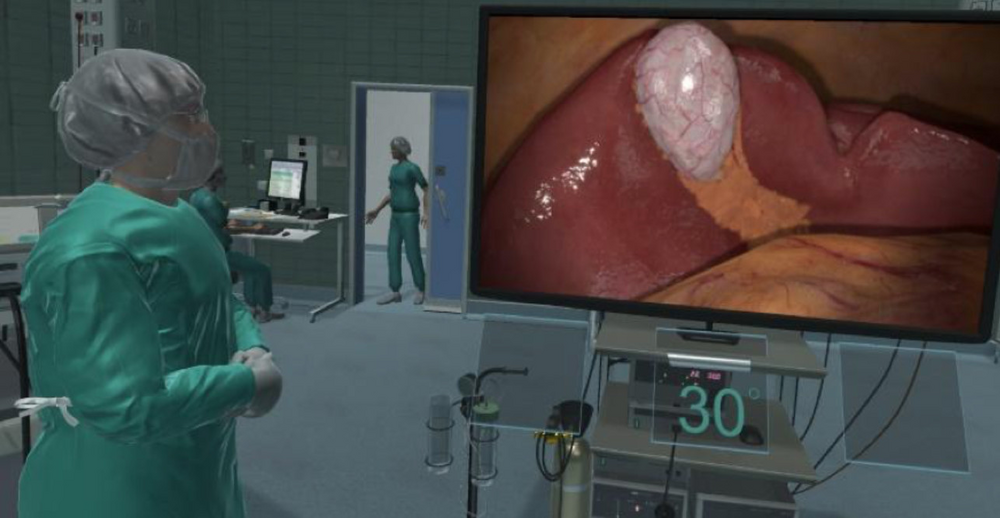

That helped Ganni to develop different tools like automatic software-based tracking for surgical skills evaluation and designing virtual reality (VR) environments that are both personal and relevant to surgeons practicing in different countries. “There are different cultural aspects when designing VR,” he said. “A surgeon in India interacts with his team differently than a surgeon in the Netherlands. There are different languages and cultural dynamics, it’s all different. You need to design with that in mind so it’s very natural when surgeons train.”

It’s complicated

Laparoscopic surgery is more complex than traditional open surgery. It requires a different set of skills and presents new challenges like handling complex instruments, operating with a significant loss of haptic feedback, dealing with the counter-intuitive manipulation of the instruments, hand-eye coordination and the two-dimensional representation of the three-dimensional operating field. There are various simulation-based training methods which have proven to be effective, including box trainers, animal models, VR and augmented reality. But could they be better?

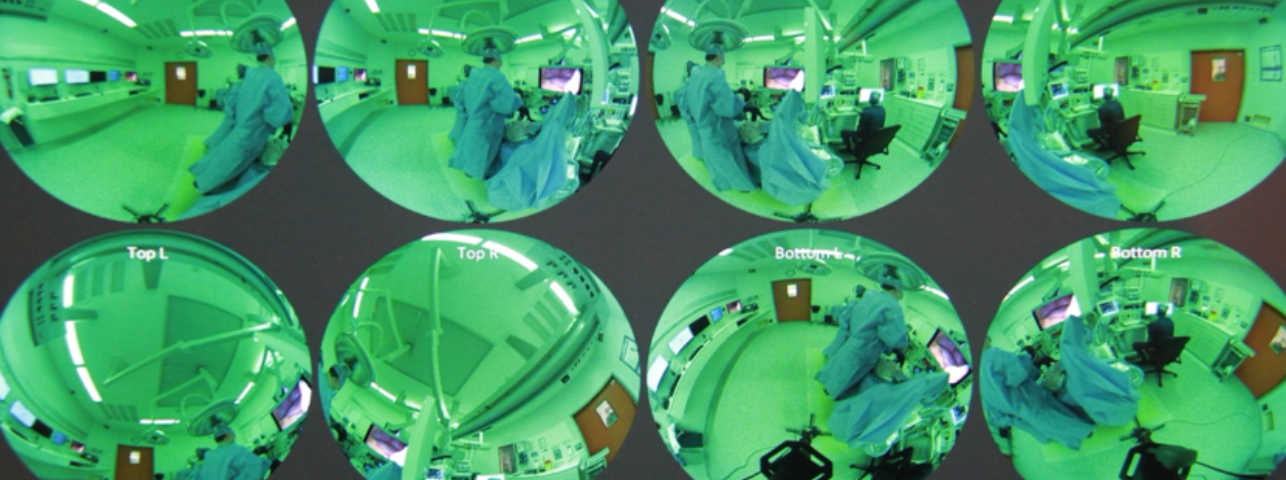

Virtual reality that’s even more real

Ganni thinks so and proposes that by building on these methods, surgeons can experience an even more realistic training environment. “In my thesis I proposed several tools, but then taking it a step forward and using projection systems onto a room,” he said. “If you have an empty room with a 3D projection then it feels like you are in whatever scenario you want to be in. Be it a critical situation or an operation theatre or a war zone where surgeons need to operate in teams. There is room for teams to operate in these bigger environments so it feels more natural.” In addition, Ganni proposes that training should include realistic distractions that surgeons might experience during surgery.

It's about more than laparoscopy

Although the focus of Ganni’s research was on laparoscopic surgical skills, he says that the implications are applicable to all medical education specialities. He plans to continue his research in India at the family run GSL Medical College. “Going forward I just want to focus on building what’s best for medical education using our skills lab,” said Ganni. “I want to keep taking forward the lessons I’ve learned and keep on advocating for newer technologies. But sticking to the basics in the end, not creating something radically different but that complements the existing framework in medical education.”