We have to fly less. And make flying climate-neutral.

Climate change is our reality. And while aviation contributes a lot to the well-being and prosperity of people around the world, it contributes to this climate change. Flying as often and as far as we do now is simply no longer sustainable. We all need to make much more conscious choices. Is it really necessary to make this trip? What is the most environmentally friendly mode of transport for the journey?

At the same time, the real expectation is that not fewer, but many more people worldwide will fly. This is because more and more people worldwide are affluent enough to travel. For that reason, we should be fully committed to making aviation as climate-neutral as possible.

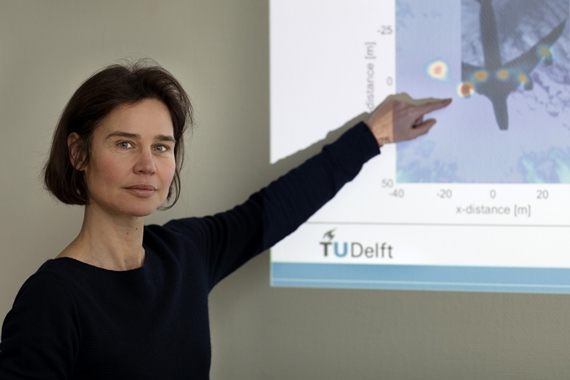

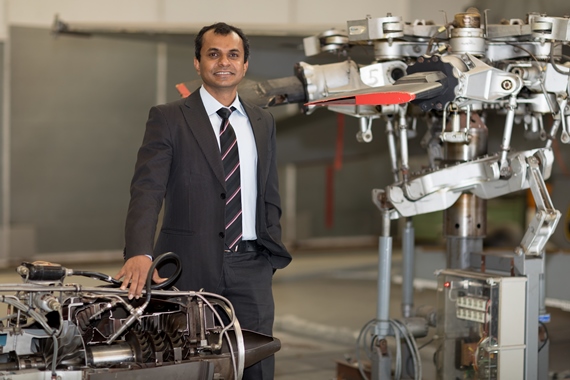

At TU Delft, we are convinced that with knowledge, technology, innovation and a new generation of aviation engineers, we can make a major contribution to climate-neutral aviation in 2050 or earlier. To develop the right innovations and also get them introduced quickly, we cooperate with other knowledge institutes and with companies from the aviation sector and the manufacturing industry, among others. In this way, we contribute to ensuring that aviation can continue to connect the world for future generations.

Henri Werij

Dean Faculty of Aerospace Engineering TU Delft

How do we work on making aviation sustainable?

Sustainable Aviation Projects

Collaborations

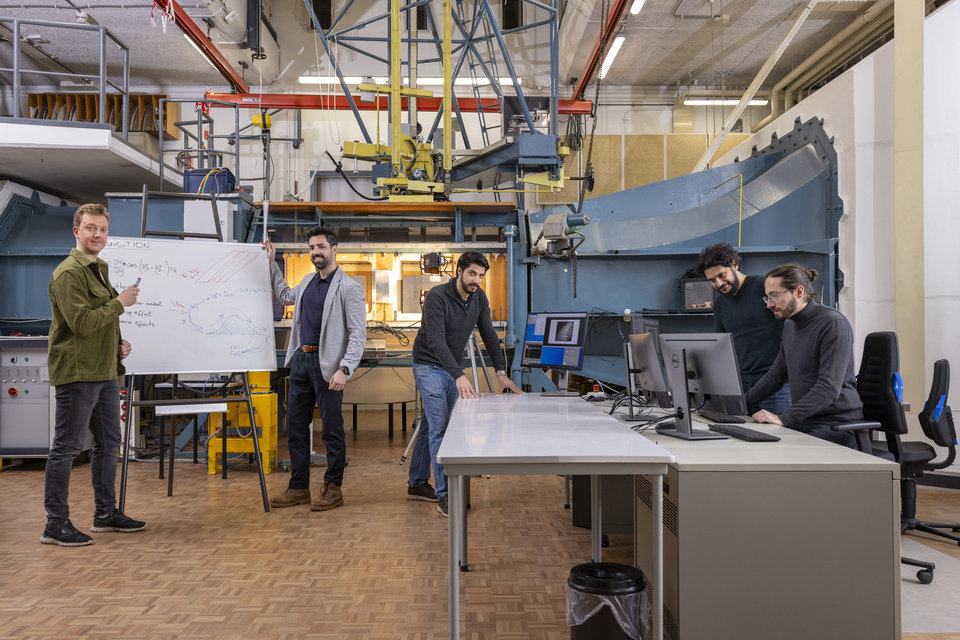

We joined forces with many parties to make a significant contribution to climate neutral aviation. Here’s an overview of some of our main collaborations.

Soaring Towards a Greener Future: The Path to Sustainable Aviation

You can build a fantastic, sustainable airplane. But if there’s no airfield where it can re-fuel, because it’s hydrogen powered, and if it can’t land, then it won’t be used. You’ve just created a museum piece. The entire system must be addressed. And there is urgency: improving efficiency is much-needed in the European aviation industry, which has to become C02-neutral by 2050.

What does it take to achieve sustainable aviation? How to accelerate innovation? And what can we do for existing aircraft? In this Pioneering Tech video, Rinze Benedictus (Professor Aerospace Materials & Structural Integrity) and Marios Kotsonis (Professor Flow Control) provide the answers.