“Pro bono architect”, Michiel Smits wants to challenge the very model of modern-day Development Aid which he perceives as top-down and capitalistic. “We’re trying to penetrate this wall of ‘I’m the expert, I know what is right and although you can’t do this yourself, we’ll pay people from outside to do it for you’.” Much better to assess people’s existing knowledge and capacities, and then advise them how to improve, suggests Smits who is currently helping people in remote African communities build and maintain better houses for themselves.

People want “modern houses”

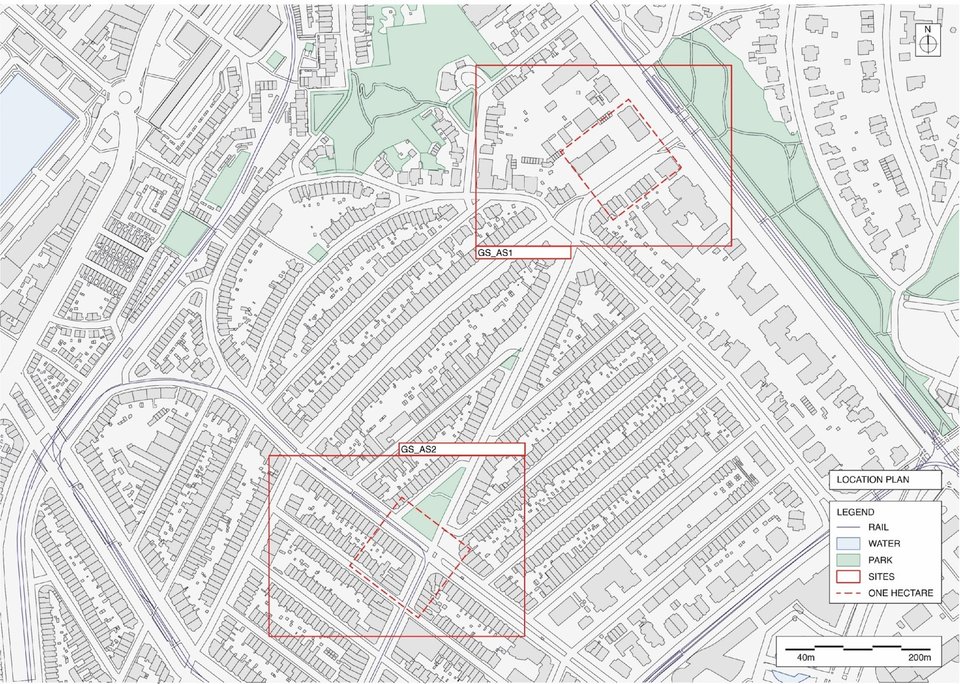

Chepchoina is a village lying high on the slopes of Mount Elgon in western Kenya, just five minutes walk from the border with Uganda, and 90 minutes drive from the nearest town. In this remote community, 75% of the inhabitants live in mud-based huts built according to traditional or ‘vernacular’ architecture, using the same materials and techniques that have been used for centuries. And the traditional design can also be unsuitable for the climate; for instance at 2000 metres altitude, the temperature in these Mt. Elgon communities drops sharply at night and people get sick because of draughts blowing through massive cracks in the walls of their current houses. “Yet these inhabitants continue using old techniques to build and repair their houses simply because they don’t know how to improve them themselves.” In a recently conducted survey of 200 households, Smits discovered that families are unhappy with their houses and want modern ones, but as these require skilled labour and non-local materials, they are just too expensive.

Improving on traditional architecture

So Smits, who works part-time as a lecturer in the Netherlands to support his PhD study, has set up a research project which involves finding out first what the local people already know about building houses and what they have, and then advising them on how they could build a better house based on those capabilities. This contrasts with the more conventional ‘top-down’ development aid approach, which prioritises building institutions instead of making direct improvements to the local inhabitants’ quality of life. “In many development aid projects, it’s often decided – without consulting the people who live there – that a community needs a hospital. So people raise funds, bring in an architect and build it.” Then later, when the aid organisation wants to pass on the running of these projects to the local communities, there are usually “kind of obvious” problems, says Smits, “bearing in mind that these people live in extreme poverty in a mud shack. And these people are supposed to run a facility to a western European level? There’s no way that these projects can just be handed on to the local community.”

New knowledge spreads

Smits believes that a better way to help is to look at what people already know and have and then come up with feasible and easily available alternatives: for instance, better ways to use traditional building materials. “We could advise communities how to make compressed adobe bricks using basic tools and local soils, and then show them how to stack the bricks rather than using the traditional technique of using mud and cow faeces.” Then once people understand how to improve their building skills and materials, they can help each so that even after the ‘building advisor’ has left, this knowledge can spread throughout community without external help.

Putting his theory to the test, Smits has set up a research project involving four carefully selected and socially similar families living in the Mt. Elgon communities. Over the next six months, each family will build their own house, advised by one of the four architects, from Greece, Kosovo, Kenya and the Netherlands, and each team will also include a third-year Bachelor student from the Avans University of Applied Science.

Children draw their ‘dream houses’

The teams use board games, drawing and model workshops to find out what sort of house the families, including the children, dream of. This helps the architects understand what’s important to the families, and also gives them an idea of their aspirations, which are also not always the best choice for the local environment. “Many people living in poverty aspire to live in a nice brick house with plastered walls, concrete floors and roofing sheets, but even this type of house, although relatively luxurious, has problems,” says Smits. “When it rains, the noise on roofing sheets is deafening, and when it’s sunny, it’s far too hot.” As the project progresses however, the building teams hope to be able to advise people on better designs and building techniques.

Advice increases self-reliance

Given that 60-70% global population lives in similar circumstances, Smits hopes to develop a general methodology within his post-doctoral research for use around the world; a methodology that builds on traditional skills and capacities, and boosts self-reliance “assessing possible alternatives solutions and offering the advice that will enable them to become more self-reliant.”

For more information

www.theruralhousingstudio.comGlobal Research Areas