How can we improve healthcare access through affordable and accessible medical devices that are designed for low-resource settings in Africa and beyond? That is the question Karlheinz Samenjo, TU Delft | Global Initiative Research Fellow, has been answering over the last 3 years. Samenjo’s story started in Cameroon where he was born, continued in Kenya where he ran his first business and studied mechanical engineering at the University of Nairobi, and has now taken him to the Netherlands, where he is close to finishing his PhD thesis about circular medical devices at TU Delft. “When I started my PhD in 2019, my life changed”, says Samenjo. “I found a new me that enjoys science like crazy. Yes, even writing papers. I never realised it before, but I am an academic. I might be an entrepreneur in mind, but I am a scientist by heart.”

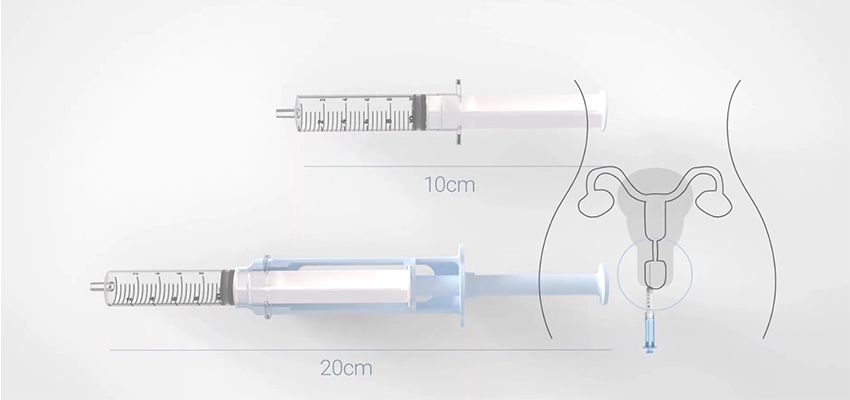

During his research, Samenjo designed a simple, durable device that can be used during gynaecological procedures. It is an extension piece that makes readily available syringes long enough to administer pain medication into the cervix. Long syringes are usually unavailable in low resource settings, making the much needed pain relief impossible to get to the people that need it.

The test results have been great so far and Samenjo is ready to bring his device to the Kenyan market so that hospitals can start using it outside of research settings. This is where Samenjo’s current startup, Chloe Innovations, comes in. Samenjo explains: “In most cases, a startup means business. For us, Chloe Innovations is first and foremost a vehicle to implement what we’ve been researching into society, to get the device to the people that need it. The company helps us navigate through approvals, clinical trials, certifications, and so on.”

Science and impact

Chloe Innovations shows how science and practice go together by rule for Samenjo. “I think scientific outcomes should benefit people, organisations or the planet. Research should not end with a published paper but should transition into society. In my publications I’ve always aimed to outline the steps to go from design all the way to the market. For example ways to implement the results, what pathways are available to do so and what else is needed.” Samenjo has noticed that his way of doing research is not yet the norm in, what he calls, the hardcore scientific research. “Most scientific research stops at key findings and discussions and rarely looks into societal implications or impact real life. I think academia should promote furthering scientific outcomes into societal impact more.”

Over the last decade TU Delft has aimed to change this with the Global Initiative program. Scientists use their expertise to find concrete solutions for worldwide problems, in close cooperation with local partners. Samenjo got in touch with the university for the first time in Kenya in 2017. “I had a job in business, but I kept thinking back to my time as an undergraduate student, when I worked on making medical devices. They were still on my mind, but I did not have the skill set to dive into the scientific part of designing.”

Samenjo decided to dive into academia again, but he declined opportunities to go to reputable universities in the United States. “I wanted to go to Europe and was drawn to the Netherlands specifically.” Samenjo met with people from TU Delft after he bumped into a Dutch student that was in Kenya to work on a malaria based medical device. From there, everything clicked. “The researchers from Delft did work I relate to so closely and they showed true interest in African education and scholars.”

Before Samenjo could start the PhD he wanted to do, he came to Delft to do a master’s degree in Industrial Design Engineering. “That felt a bit weird sometimes. I was older than the other students and had already been working on my career for a while. I viewed that second master’s as my sabbatical. I got to learn new things and grow as a person. It turned out to be the perfect choice.”

Hub

Over the years, the researcher found that students at TU Delft are very interested in his work. “I get emails every week”, Samenjo explains. “They want to know how to design for the Global South and go there. The other day, students asked for help to develop an AI algorithm that will help improve water drainage in Kenya.” Questions like these have made Samenjo wonder: can we create a collaborative master’s program in biomedical engineering and design? There will be courses in Delft and Nairobi, possibly connected via an online platform, where both Dutch and Kenyan students can study in both places. Samenjo: “They can exchange skills and ideas and learn a great deal from each other. It will result in a continental transfer of knowledge. I collaborate closely with TU Delft | Global Initiative and partners in Nairobi to implement this idea.”

To achieve this, Samenjo’s goal is to set up a TU Delft hub in Nairobi. “A hub will spark interaction. I know many Kenyans who want to remain in Africa, as well as Dutch students who want to stay in Kenya and keep working on their projects. As of now though, there is a lack of high-tech tools for rapid prototyping and small scale trial manufacturing. The hub can provide the necessary services which locals and people from TU Delft can make use of when in Kenya. Everyone can act on their own ideas, create prototypes, manufacture designs, and test them directly in the field.” Samenjo envisions how students find jobs at local companies to help them figure out high-tech design in collaboration with locals. “Those students that were developing an AI algorithm? They can go to the hub, work with locals, start companies, and reach their goals all in one place.” The researcher emphasises how the hub will make TU Delft more visible in Nairobi, Kenya, the so called Africa’s tech hub or Sillicon Savannah, too. “I wish we had more African students and researchers in Delft. The hub will help attract them, as well as local collaborators.”

Future

However ambitious his plans are, it doesn’t stop there for Samenjo. The engineer wants to continue working on Chloe Innovations and shift more of his focus to Central-Africa, specifically French-speaking Cameroon where he was born. “Francophone communities have been neglected as research has stifled because of language differences. We want to bring our research and devices to those countries, to help improve the healthcare system in areas that are even more limited in resources.”

Now that his PhD is coming to an end, Samenjo has started wondering about his future. He clearly knows what he wants, but how will he achieve his goals? “I want to stay in academia and in Delft, and I wish to continue building collaborations with other African universities, but I keep asking myself: can I make it? I don’t have examples of other African professors in Delft who have taken a similar path as me and who I can learn from. This scares me. It makes me wonder if I should even try. What if I fail? Have I then set a wrong connotation for those who will come after me and perhaps do better? And if I end up representing the people who succeeded, can I handle the pressure of being the first one? It feels like I need to succeed for the people coming behind me and be their example.” Samenjo explains how this pressure is not actively put on him, but arises due to circumstances. “This is a problem bigger than TU Delft, the university did not cause this. Perhaps it is also a human thing, being scared of being the first. I have faith I will figure it out. I might just jump into the deep end and swim.”

Whichever road he chooses, Samenjo hopes to inspire people with a similar mindset to him. “We need more Karls! We need more people designing for less privileged communities. This goes well beyond Africa too.” Samenjo wants to develop his research so that academics can apply it in low resource settings globally, including Europe. “Low resource environments are everywhere, from big cities to regions that suddenly change because of a natural disaster or war. It is not about poverty, it is about resources. If you truly want to create impact, you have to think differently and creatively. I think the students are ready to go for it.”

Want to learn more? Check out below video's on Karlheinz' work:

Opening Academic Year 2021

The Chloe Device Explained

Published 2024. Author: Michelle Wijma

Global Research Areas