Like the energy transition, the transition to a circular economy impacts the way we use space. So how should we go about planning structural reuse and value retention? For students on the Urbanism Master's track, this is not merely a theoretical question. A range of spatial strategies have recently been put forward for a circular South Holland region.

In Delft, aspiring urbanists learn to look at spatial functions and processes on various scales. They start by considering the district and neighbourhood levels before examining the nature of interconnections in the city. In the Spatial Strategies for the Global Metropolis studio, they analyse the region. “Generally, the larger the scale, the more complicated things get”, course coordinator Verena Balz explains. “We teach students to make connections between the various scales.”

Switching between scales

For the past five years, the curriculum has focused on exploring the spatial consequences of a circular economy in depth. What effect will it have on the environment if resources and materials are circulated in local and regional cycles? As subject lecturer Alexander Wandl explains, “Transitioning to smaller-scale production and distribution chains based on reuse requires a different set-up. For instance, short distances and efficient connections between facilities for the collection of waste, recycling raw materials and the production of semimanufactures – or different types of storage space. Where do you need to create, reserve or redevelop space in areas where there are already competing claims on space? How do you accommodate functions, buildings and infrastructure so that the space is not degraded in terms of quality, and preferably gains in quality?”

By switching between scales, students discover and unravel the various threads in the web of production and consumption, including the various interests and parties involved. Then they proceed to consider how those threads can be rearranged and rewoven into more sustainable fabrics. Wandl: “As up-and-coming designers and spatial planners, they learn how to identify and define the patterns and structures of a circular economy. This gives them the tools to guide both conceptualisation and policy-making on future spatial use as professionals.”

The real world

Although various Dutch authorities recently arrived at a vision on the circular economy and formulated long-term objectives, there is still no action plan, certainly with regard to spatial planning. As the real world provides the best learning environment, students spend a lot of time on practical assignments. The South Holland region was the main focus in the past year. The sustainability of material flows in the building, agricultural and food sectors as well as the plastics industry are high priorities on the provincial agenda. “The authorities involved help us to define realistic assignments. In this way, we immerse our students in the real world”, course coordinator Lei Qu explains. “We call this a ‘situated learning environment’.” Balz adds: “The province has appointed transition managers. They are our partners; they provide relevant policy documents and data files, participate in teaching and bring together the results for their constituencies.”

The province is working to develop its spatial strategy for the circular economy in the coming year. These student projects really help us to imagine what a real-life circular strategy could amount to in terms of spatial development if we were to think in big ‘what-ifs’.

Jeroen van Schaick, regional designer, provincie Zuid-Holland

Intertwined flows

Master's students Rosa de Wolf and Jonah van Delden first explicitly encountered the concept of a circular economy during the course.

I now realise the extent to which all kinds of material flows are intertwined. Something categorised as waste in one sector may become a raw material in another. That's fantastic, isn't it?

Trying to grasp that potential at the regional level can be very complex, according to Jonah, “because you are looking both at systems and details.” For instance, if you want to reduce the use of artificial fertilizer to promote a more natural form of circular agriculture, that will have consequences for the entire chain: from land use to the products on supermarket shelves. “It's fascinating to look at things at different levels and to discover the connections.”

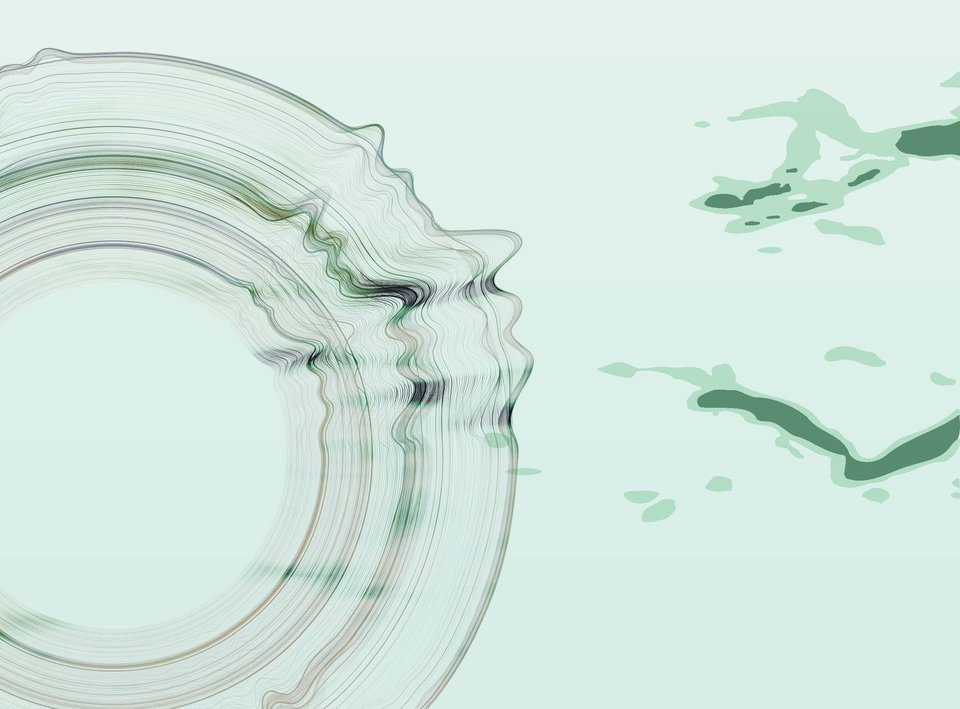

Groups of students spend ten weeks delving into the subject matter. Starting from the overarching visions on the circular economy of the Dutch government and in the EU's Green Deal, they work towards spatial strategies for parts of the region. Among other things, those strategies aim to combat social and spatial injustice. “What steps need to be taken to achieve the generic goals in five, ten or twenty years?” One of the spatial opportunities identified by Jonah's group (Daan Helmerhorst, Lisanne Meijer, Jonah van Delden) is to make better use of urban fringes for sustainable food production. “Disadvantaged population groups often live on the outskirts of cities, these areas can develop by involving them in this spatial strategy”. The students’ plans sometimes display a striking degree of open-mindedness. “Others take account of the consequences of rising sea levels, and propose that flooding is a possibility for all spaces outside of urban areas.”

A critical issue

Design research into a circular South Holland also prompted Rosa to consider the importance of personal choices.

I've only recently become much more aware that you can contribute significantly to a circular economy as an individual, by doing something as simple as adjusting your lifestyle. It's not only big organisations that can make a difference.

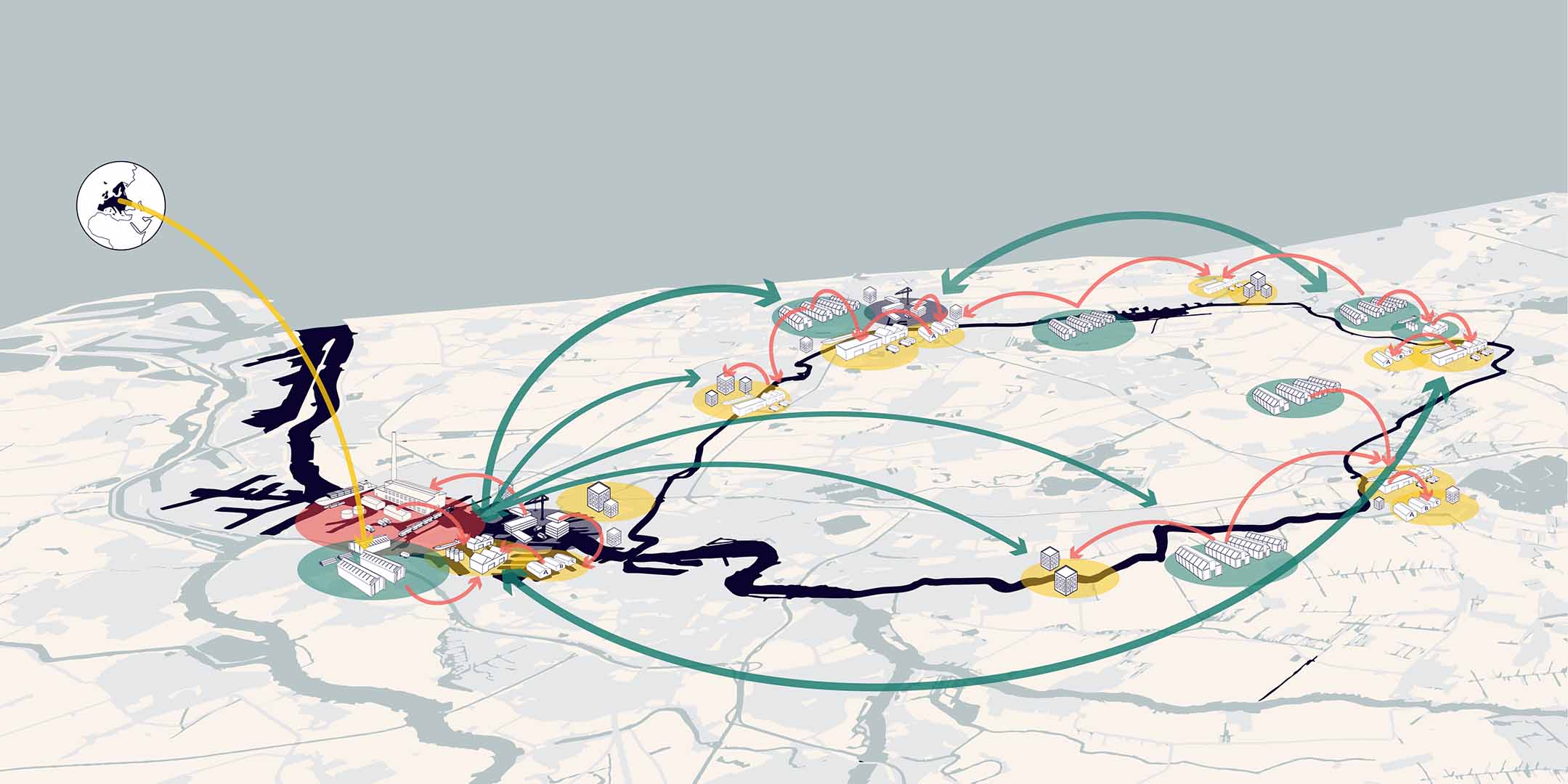

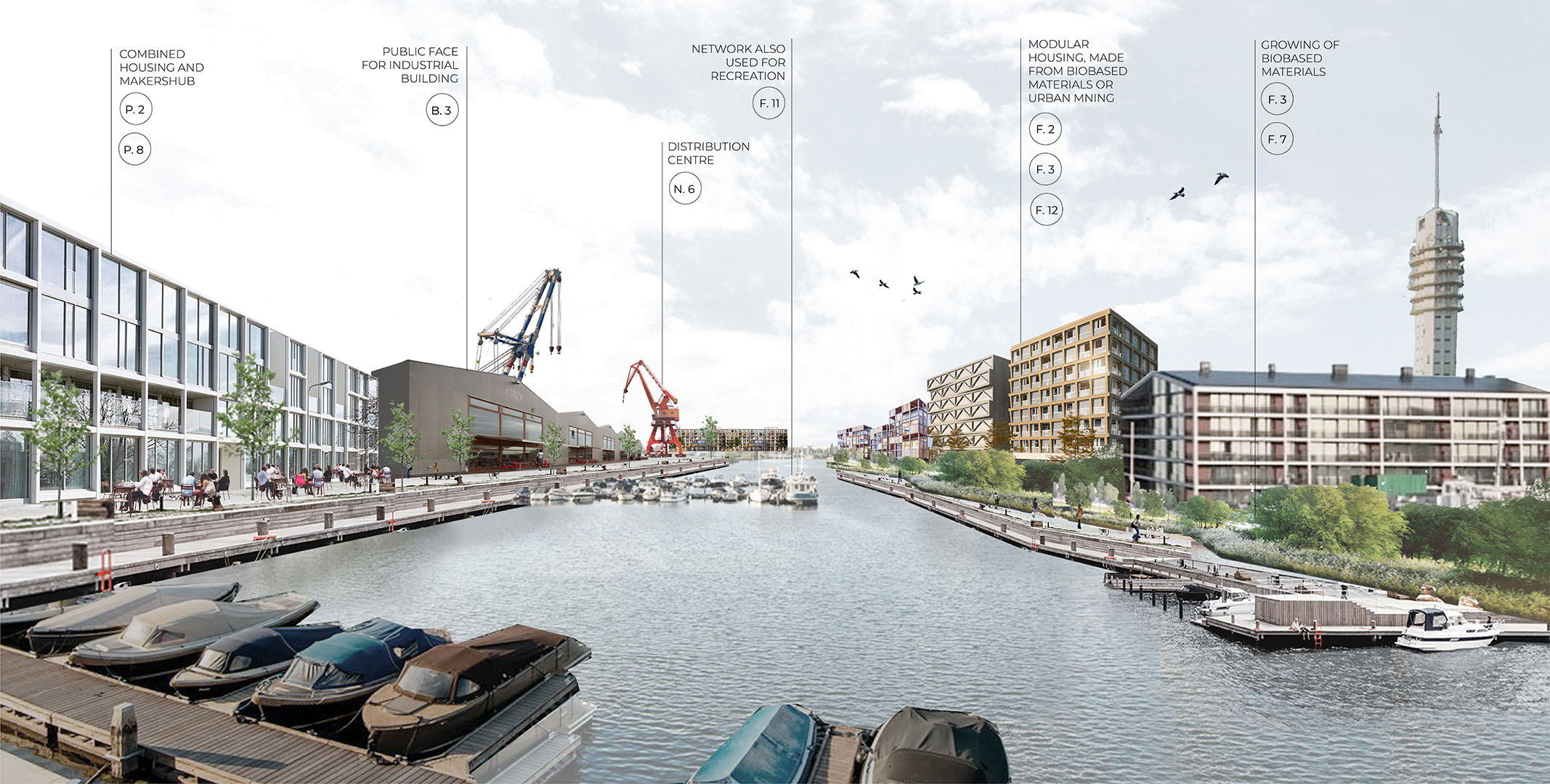

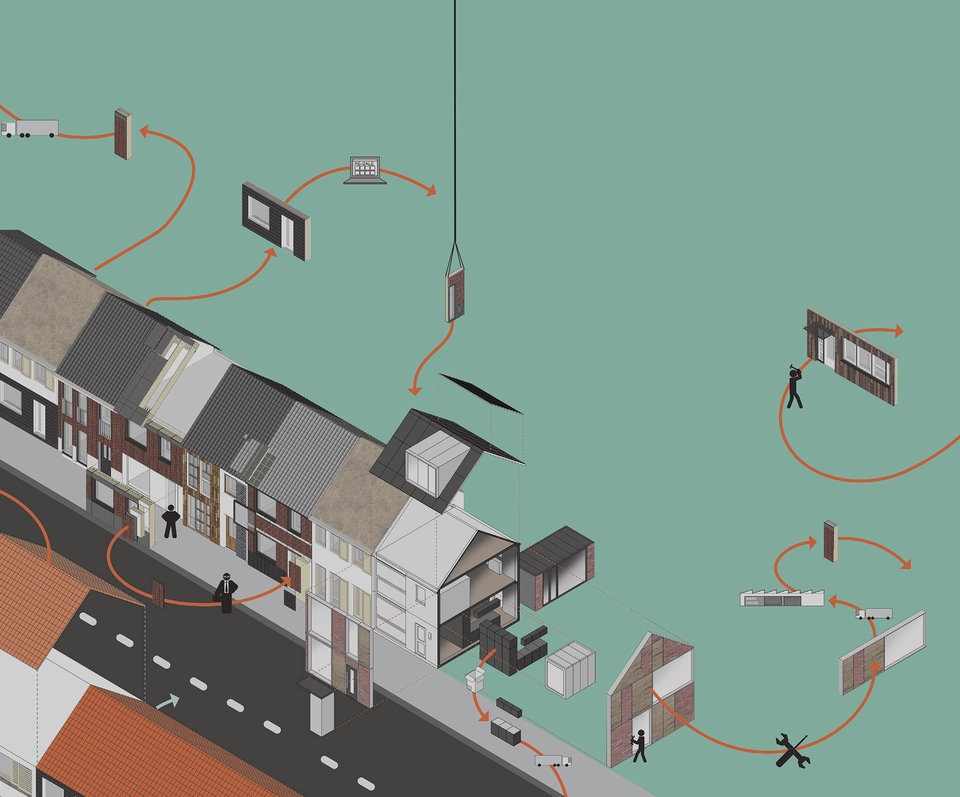

Her group (Monserratt Cortés Macías, Thomas van Daalhuizen, Paula Nooteboom, Siene Swinkels, Rosa de Wolf) focused on the developments towards a circular building sector. Large-scale use of fresh concrete is a critical issue, particularly in view of the scale of the provincial building plans. The province wants to know what the sustainable alternatives are. “We have conceived a distribution network for bio-based construction materials such as wood (CLT) and hemp lime.”

The network consists of local hubs for separate materials and a central hub in the port of Rotterdam. As these sites for storage, transfer, processing and construction are situated along a waterway, demolition waste, waste flows, raw materials and building materials can be distributed across the region relatively easily and cleanly by waterborne transport. “South Holland is already densely populated and the need for housing is increasing all the time, so we are faced with the practical consideration of how to combine a location such as this with residential needs.” And that's not only a matter of complying with environmental rules, she points out: “The main question is how to create a pleasant living environment without the two functions conflicting.” Rosa’s group concluded that such conflict can be avoided by having all heavy industrial activities, such as recycling the steel that is needed for construction, take place in the central hub. “Without causing too much nuisance, the local hubs could not only be part of the residential areas, but could even make them more attractive.”

This story is published: June 2021

More information

Find all the proposals (2020-2021) here.

Interested to see what the students have been working on this year? Check out the results of the 2021-2022 edition of the studio 'Spatial Strategies for the Global Metropolis'.