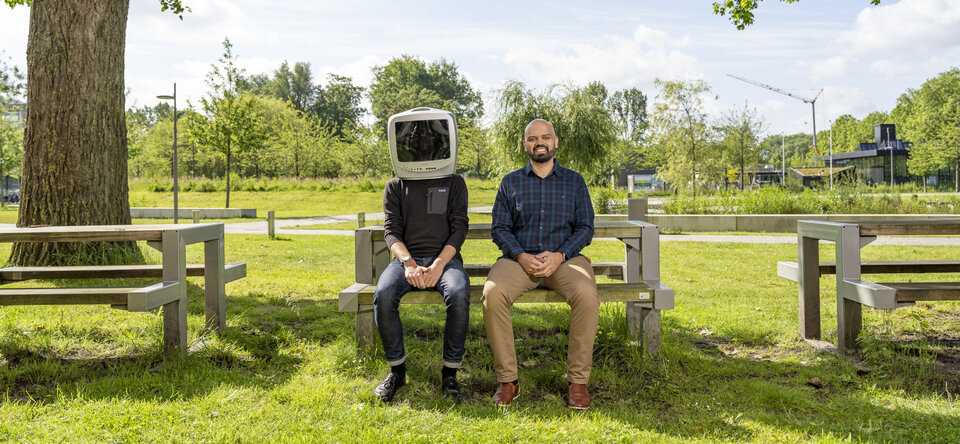

With all the uncertainties we are facing, climate engineering (geoengineering) is not a desirable means of combating climate change, but in the future may well be an unavoidable one. Philosopher of technology Behnam Taebi uses an ethics-based approach to try to bring some nuance into the search for technological solutions. Using the Climate Action Hub, he wants to build a bridge between science, citizens and politicians.

Hanging a solar shield in space or injecting aerosols into the stratosphere to reduce the amount of sunlight reaching the earth are interventions that we can hardly begin to imagine. Yet scientists all over the world are working on climate engineering. Their work is not only focused on technological aspects. According to Behnam Taebi, professor of Energy and Climate Ethics and technology philosopher, there are many uncertainties surrounding these large-scale interventions. “You really don't want to implement technology for which the risks and consequences are not sufficiently known. For example, how will they affect precipitation? And what will happen to the climate if we suddenly stop using a certain technology?”

Lack of nuance

Taebi has spent over 15 years exploring ethical issues within energy and climate technology. His interest goes back to the nuclear energy debate. “I was really annoyed at the way this debate was taking place. It was very black and white, with a complete lack of nuance and understanding of the technological complexity of nuclear energy. There are many different methods for generating nuclear energy, different reactor types, fuel cycles and possibilities for recycling. I see these same black and white attitudes in the discussion on climate engineering. We really shouldn't consider it as the ultimate solution or reject it altogether, but explore a wide range of applications, map out the risks to the best of our ability and weigh up all the pros and cons of each specific type of climate technology, as we also do for nuclear technology.”

Ethics at the forefront

As a philosopher of technology, Taebi aims to ensure ethics are at the forefront of the quest for energy and climate solutions and the associated decision making. “All too often ethics are no more than an afterthought. Take the discussion on shale gas for example, where politicians and project developers made the mistake of first appointing a site for explorations only then involving the local residents. Citizens’ concerns were mainly about the question whether the Netherlands should be drilling for more gas at all (conventional or unconventional), while the policy-makers and project developers were trying to convince them of the low technological risks of shale gas drilling locally. So the discussion came at the wrong moment and it was not about the subject people were primarily interested in. It is important that we initiate the discussion on the desirability of a certain technology long before the decision-making phase, and also distinguish between different kinds of technological possibilities.”

It is important that we initiate the discussion on the desirability of a certain technology long before the decision-making phase, and also distinguish between different kinds of technological possibilities.

Climate Action Hub

In order to build a bridge between science, citizens and politicians, TU Delft has launched a Climate Action Hub in The Hague at the end of September: a physical and virtual place where important climate issues can be discussed. Taebi: “The Hub is an extension of the Climate Action Programma of TU Delft. We hope the Hub will bring science closer to politics and decision making and fill in the blanks in the climate debate. The scientific blanks are the things we don't yet know and still need to know in order to gain a better understanding of climate change and possible solutions. At the same time, we need to take into account the blanks, both in the understanding of policy-makers and in society: what are our societal needs.”

Translation to politics and policy

As the main representative of TU Delft in The Hague, and a main driver behind the Climate Action Hub, Taebi's task includes facilitating the discussion between science and politics. “With our knowledge and expertise as a university of technology, we can provide resources for members of parliament, policy makers and advisory bodies. Even though growing attention is being paid to ethics in major social discussions such as climate change, it is still a challenge to incorporate ethics in actual policy. At TU Delft, we can help enable this crucial step in policy-making”

Taebi adds that the Hub is not just for TU Delft. “We hope to also gather intellectual human power from other knowledge institutions in order to collectively address the thorny questions of climate change”. One of our ambitions is, for instance, to set up a national climate engineering expertise centre together with our colleagues from other Dutch universities.”

International cooperation

Certain climate engineering technologies also requires international cooperation, continues Taebi. After all, climate change and the use of climate engineering have consequences that transcend national borders. “It is crucial that we make good agreements and also stick to them. Who decides which country may use which technology and when? And who is responsible for any unforeseen consequences? We also need to involve developing countries in this debate. The extremes will only become more extreme. It would be disastrous, for instance if there was to be a lot more rainfall in a place where it already rains a lot, or our interventions were to have negative consequences for crop yields.”

Better not to use

Taebi stresses that climate engineering is just one of the many flagships of the Climate Action Programme and the Climate Action Hub. He feels the academic activities surrounding climate engineering should not be considered as a vote in favour of their use. On the contrary, there are certain technologies that Taebi hopes that we will never have to use. “Solar Radiation Management (see box, ed.) in particular is very undesirable as things stand now. We know very little about its consequences, both in time and space. Carbon capture technologies are a much more obvious solution and are already being used in some places. However, the gold standard remains mitigation: reducing our carbon emissions. Discussions on climate engineering should not distract our attention from this gold standard.”

Weighing up risks

Yet Taebi feels it is increasingly likely that we will reach a point where measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will no longer help; the point of no return. “At that point, climate engineering may prove an important means of combating global warming. So we need to make sure we have the technology at our disposal.” Taebi acknowledges that we cannot totally eliminate risks. “Indeed, there are always risks involved with technological developments. The question is, what risks do we consider acceptable and for whom, and how do we offset these against other risks. One technology will almost inevitably score higher on desirability than another.”

Wary of techno-optimism

As an engineer, Taebi is fascinated by the possibilities and opportunities that technology offers. Yet, in his role as philosopher of technology, he feels he needs to be reflective and include potential risks and hazards “We need to make sure we do not blindly trust in technology as a solution for everything. So I am wary of techno-optimism. There are many catches to technological solutions. This could mean that we may want to exclude the use of certain technologies in the future. But at this point in time we don’t have the luxury of excluding too many technological options. The climate question is just too large and complex for that.”

Types of climate engineering

Climate engineering can be divided into two categories: solar radiation management (SRM) and carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies. SRM involves the partial reflection or filtering of sunlight in order to reduce the temperature on earth. CDR refers to methods for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and sequestering it, for example in empty gas fields under the seabed.