How can the social housing sector make the transition to circular construction and renovation? To answer that question, eight building components were tested in trials in a continuous feedback loop between practice and research. Doctoral candidate Anne van Stijn thinks we need to start seeing homes as collections of separate components.

The transition to circularity is a major challenge for society. The construction industry processes huge amounts of building materials and also produces huge amounts of demolition waste, both of which have a major impact on the environment. In fact, this industry is thought to be responsible for 40% of the world’s resource consumption, 40% of its waste and 33% of man-made emissions. Housing associations in the Netherlands need to change the way they build new homes and renovate old ones, and circular construction and renovation will play an important role. Doctoral candidate PhD student Anne van Stijn took up this challenge in her research into opportunities for the circular renovation of social housing. “I have always been involved in research into public housing,” she says. “In fact, the social housing sector is my passion. I had been on the lookout for new ways to renovate buildings for some time. The concept of ‘circular economy’ was relatively new to me. I knew straightaway it was something I needed to work with.”

Collection of building components

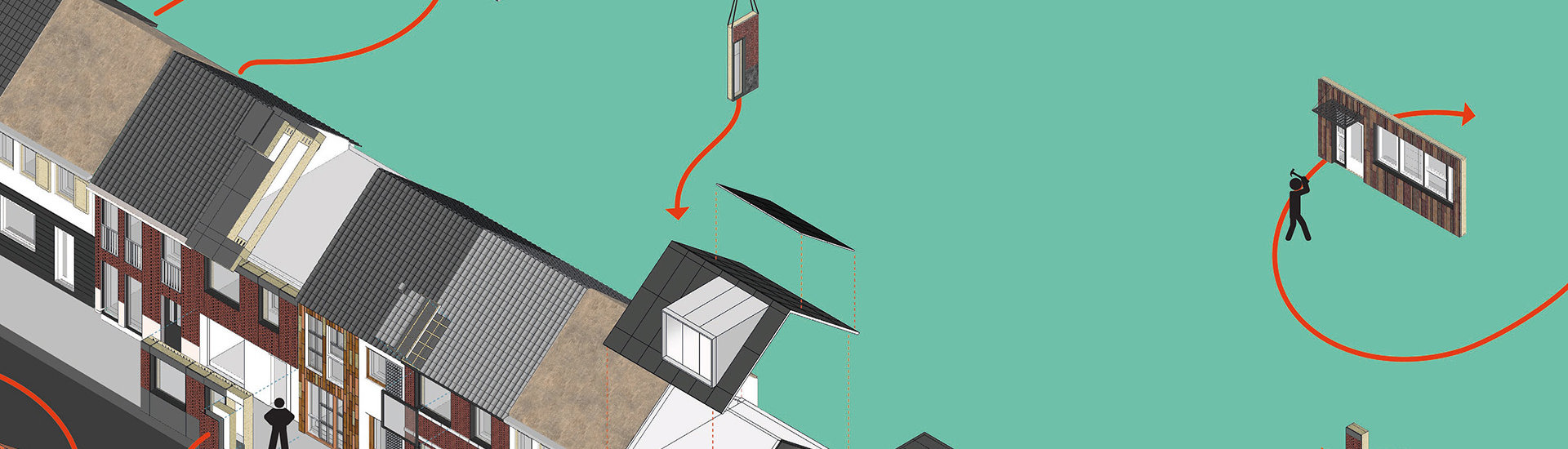

Anne thinks the solution is to consider homes as collections of separate building components. Walls and roofs are such components, but so are mechanical systems and kitchen units. “By replacing each of these with circular components during the maintenance or renovation of old buildings, you gradually make the built environment more circular. However, it turned out that circular building components are virtually non-existent. If you did a search on the internet for ‘circular kitchen’ you were shown pictures of kitchens with round shapes. The knowledge of circular design was still mainly limited to the consumer industry, not construction.”

By replacing building components during maintenance or renovation with circular components, you gradually make the built environment more circular.

Working with the professionals

“To test my idea of working with separate components, I sought cooperation with the professionals in the field,” says Anne. “I formed partnerships between housing associations, building contractors and their supply chain partners. Each group of participants designed different components for the research that were tested in the form of prototypes, pilot projects and in real-life renovation projects. We were faced with a lot of questions during the development process, such as how to design a circular building component and how to determine which design is the most circular. Those were the questions I tried to answer with my research.”

It resulted in the development of plenty of new knowledge that can be applied in practice, such as new design tools, measurement methods and design guidelines. The research focused on eight building components. “One project involved designing and installing modular extensions for sixty houses. These circular components have standard dimensions, are completely detachable and are constructed from recycled materials. Pre-used pergola wood now serves as façade cladding.”

Considering circular options

“Right from the beginning, I had one foot in working practice and the other in science,” Anne describes her position during her PhD research. “The industry needs a workable solution, but as a scientist you need to carefully consider all the options, and also be clear about the limits of what your research can achieve. When we measured the environmental performance of the various design variants, some were found to perform no better than the existing components used in the industry. And even the most circular designs cannot yet reduce the resource consumption, environmental impact or waste generation to zero.”

Long-term transition

Looking back on her research, Anne concludes that circular renovation will be a transition over the long term. For instance, not all circular designs are feasible in practice. “Renovation projects are already complicated as it is, and now they also have to become circular. I wonder if circular solutions alone will be able to deliver the required results. Maybe we should also be building and renovating less?”

The research partners endorse the importance of the circular transition, but the construction industry is currently more focused on making energy savings. “They have to meet a range of conditions, including affordability, and then find a way to fit in circularity as well. So what do you give priority to?” It made Anne realise that circular renovation cannot become reality by only focussing on individual projects and technologies. “The current form of cooperation in the supply chain and the way the costs and benefits are evaluated will also have to change.”

This story is published: April 2023

More information

Read Anne van Stijn’s full dissertation here:

- Developing circular building components. Between ideal and feasible, Anne van Stijn, ISBN 978-94-6366-674-9.

In collaboration with C-creators, Anne has translated the current scientific knowledge on circular renovation into an open access practical handbook for housing associations.

Anne van Stijn’s PhD conferral ceremony took place on 21 April 2023.

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/_processed_/0/b/csm_Header%20afbeelding%20InDetail%20-%20Stefan%20Buijsman%20-%202_01_8b72583971.jpg)