The rise of smartphones has made photography accessible to everyone, but this has not necessarily resulted in better photographs, as a quick look on Instagram or Facebook can confirm: there is a huge difference between being able to take photographs and being a good photographer. But what if this difference was eliminated? Thomas Saulou at TU Delft is working on software that can make this possible.

Before joining the Computer Graphics and Visualisation research group Thomas Saulou had long been involved with images. It all started out skateboarding with his secondary school friends on the streets of Paris when he started making videos, later on switching to photography. ‘I love taking pictures, on holiday with my girlfriend, or just on the streets… From my very first day at TU Delft, I began thinking of how nice it would be to combine my love for photography with all the technology I was learning about.’

I began thinking of how nice it would be to combine my love for photography with all the technology I was learning about.

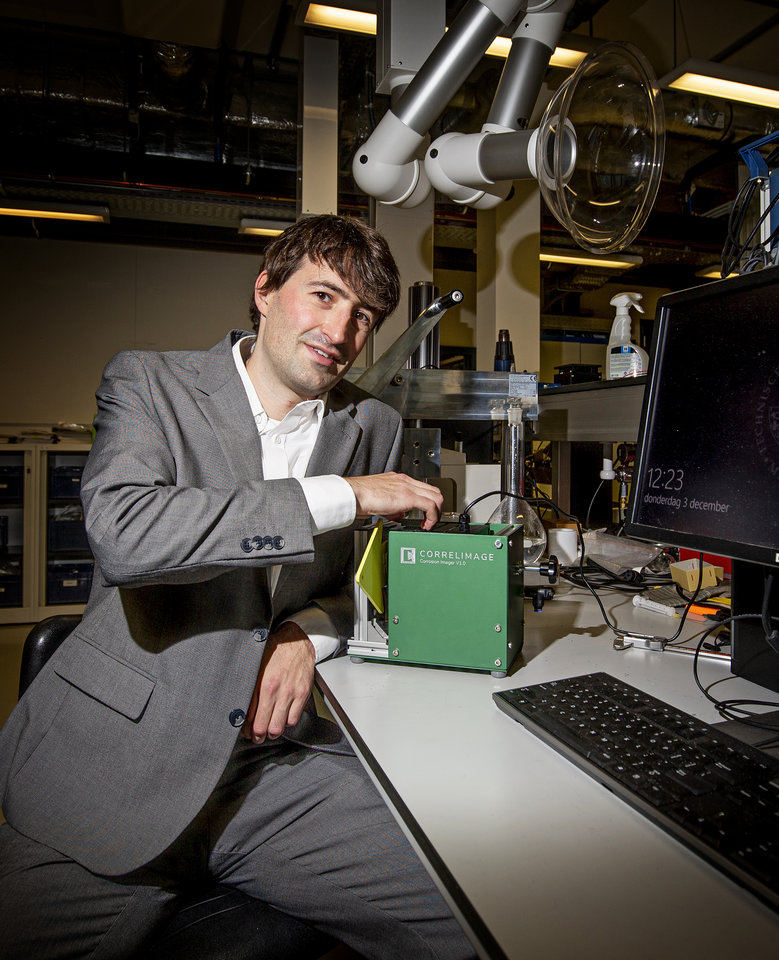

Some of Thomas’s own work as a photographer

Once at TU Delft, Thomas’s dream became reality. Professor Elmar Eiseman from the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science (EEMCS) was working on something he called “Photoshop for Dummies”. The idea was to build an artistically smart tool that goes further than Photoshop and doesn’t require the user to have any particular skills. This software would be able to make images as visually pleasing as possible all by itself. Elmar was on the lookout for someone with a background in both computational image processing and photography: someone like Thomas.

Het idee was om een slimme tool te bouwen die verder gaat dan Photoshop en waarvoor de gebruiker geen specifieke vaardigheden nodig heeft.

Artistic algorithms

But just what makes something visually pleasing, and is it possible to implement artistic traits in a computer? Although the appreciation of art – like photography – comes down to personal taste for a large part, there are fortunately a few things we all agree on. There are certain qualities that we generally either like or dislike. The lighting must be right, we like contrasting colours, and a difference in focus between fore- and background can work very well in a portrait photograph. In recent years cameras and smartphones have come onto the market that have built-in smart software that can perfectly tweak these characteristics. Getting the right balance between dark and light used to require Photoshop skills, now it’s just the “HDR” switch you flick on in your photo app. Taking a portrait photo with a blurred background no longer requires a specific type of lens, because “portrait mode” will automatically cut out your subject and blur the background exactly the right amount. According to Thomas: ‘The biggest improvements are no longer in the actual camera itself, but in the software that processes the images.’

After spending a year doing research on computational photography at TU Delft, Thomas wanted to further expand his knowledge in this area. He is now studying for a master's degree in ComputerSscience, with a specialisation in image processing, at La Sorbonne – one of the oldest and best-known universities in France.

However, nothing can influence the quality of a picture as much as its composition. Photographers, like Thomas, are aware of this and adjust their stance and framing while taking pictures to create an appealing composition, but the average person probably wouldn’t. Creating an attractive composition is the one part that has not yet been automated in cameras and phones. The goal of Thomas’ research was to develop software that can take on this task, by assessing the location and perspective of a subject in the image and automatically moving the subject in the image to a visually more appealing location, or by adjusting the perspective to fit our taste.

At some point, I got lost in exploring the artistic side.

Composition rules

But what exactly do we mean by our taste? Within photography, there are many different and sometimes conflicting rules regarding the composition of an image. So many, that picking which ones he should or shouldn’t implement in his software was perhaps the most difficult part of the whole process for Thomas: ‘At some point, I got lost in exploring the artistic side. I started to read books about compositions, about different photographers’ styles. I started a whole separate study of the different photography rules that exist. The fact that this was all taking place during the lockdown period certainly didn’t help with trying to rediscover my focus.’

Rule of thirds

Eventually, Thomas decided to start off with the basics: the rule of thirds. Imagine a three-by-three grid dividing a picture in even thirds, both horizontally and vertically. The rule of thirds states that images become more powerful and dynamic when the subject is positioned along one of these lines or at intersections of the lines.

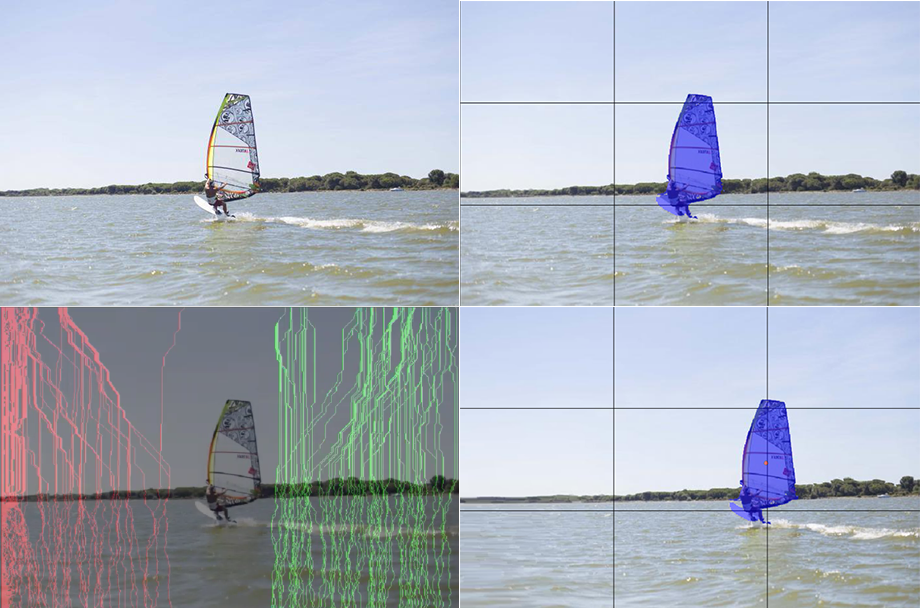

The software Thomas created is able to assess if an image meets the rule of thirds, and if it doesn’t, to move the subject to the right place. The first step is up to the user to select the subject. Then the software will cross-reference the position of the subject to the implemented composition rule, in this case: the rule of thirds. As you can see in the first photograph below, the windsurfer is positioned in the middle of the image, not along one of the lines in the grid.

Thomas’s software in action.

What happens next is what sets Thomas’s software apart from the more labour-intensive Photoshop. His tool looks at the image to the left and right of the subject, and identifies lines in the image with the least amount of “energy”, or change. These are areas where pixels can be deleted or added without the viewer noticing something has changed. In the bottom left-hand photograph these are the red and green lines. The software then moves the subject to the left or the right vertical gridline by adding or taking away pixels along the red or green lines. The results are compared to the original and the photograph that requires the least amount of intervention is presented as the end result.

From computer to phone

For now, Thomas’s software runs on a standard computer and requires user input to select the subject, for instance. However, it’s not hard to imagine the potential of software like this, especially when it is soon a part of your smartphone. Before you know it, your Facebook timeline or Instagram wall will only contain really good pictures. This is the future according to Thomas.

Text: Joost Wendling | Photography: Thomas Saulou