The Netherlands as trading country needs major spatial planning rethink. Big box warehouse construction throughout the Dutch landscape is a controversial issue. But how much and what sort of space is actually being claimed by the logistics sector, and how does this stand in relation to economic value and sustainable development? In his PhD research at TU Delft, architect-researcher Merten Nefs is studying the changing nature of the Netherlands as a trading country and the spatial effects this has.

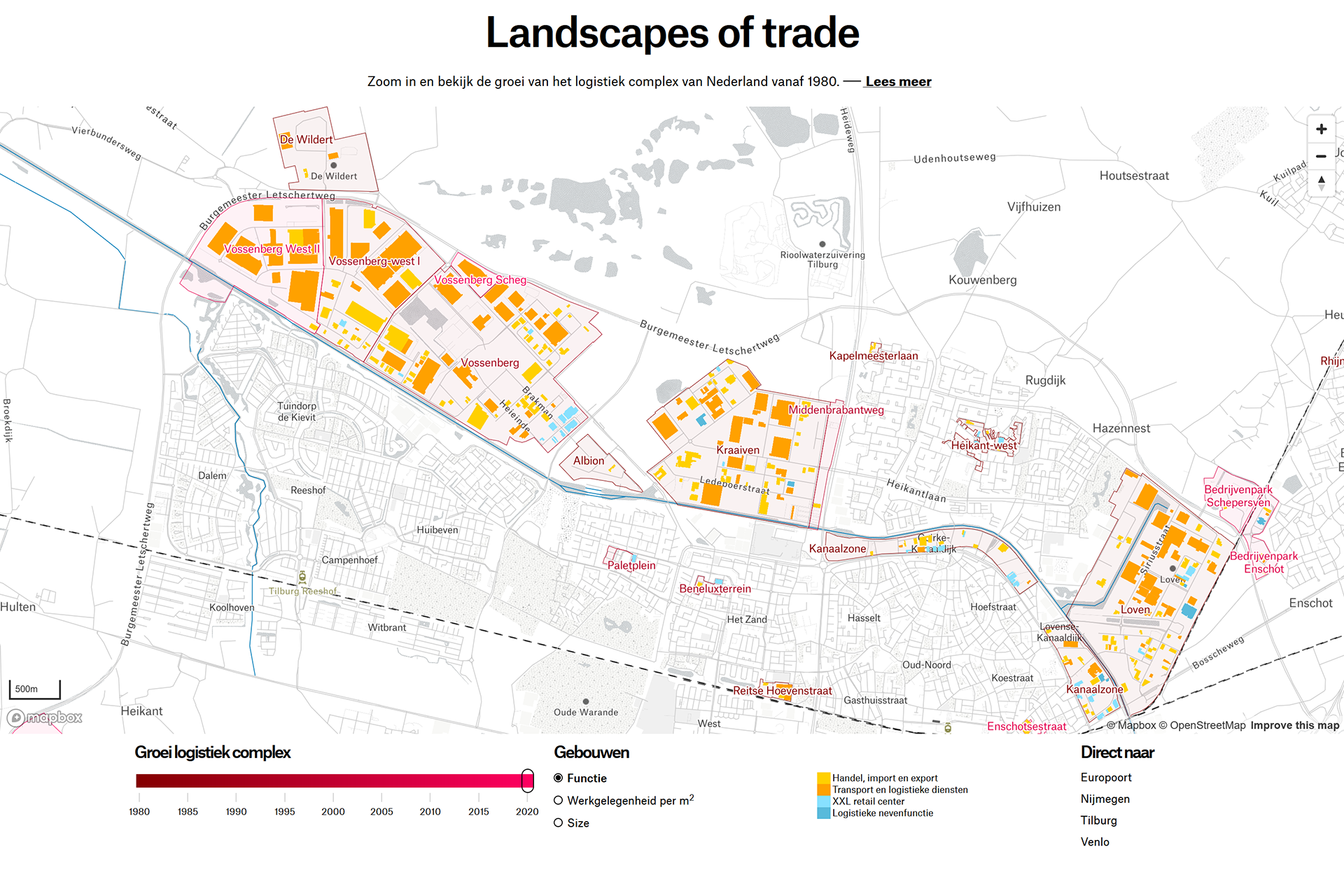

An interactive map based on data gathered by Nefs shows that the logistical complex of sites and buildings has grown hugely in the last 40 years. “It now covers around 3,000 areas and 27,000 ‘boxes, ranging from small to king-sized.” Today warehouses take up four times more space than they did around 1980. How does he explain this growth? “There are of course more of us, and we have started to consume more.” We are buying more cheap products that are quickly discarded and replaced. The shift from local to internet shopping is also associated with a demand for warehouse space. “Part of the increase can be ascribed to the role of the Netherlands as the ‘supplier’ of north-western Europe. Another important factor: investing in logistics warehouses, particularly the XXL distribution centres, is lucrative for investors. And finally, the increasingly box-filled landscape has for a long time been made possible by our lack of policies to curb the proliferation of warehouses.”

Fascination for trade flows

Nefs studied architecture in Delft. As a fresh-faced designer, he moved to Brazil in 2003, and spent several years living in the metropolis of São Paulo, where he developed a fascination for how large metropolises function. “How do all those people get their food and things? To what extent is such an enormous community dependent on all kinds of trade relationships? It was there that my interest in the Netherlands as a trading country was awakened.”

Upon his return to the Netherlands, Nefs took up a position with the Deltametropolis Association, where he started his PhD research 2019. He continued the project at his next employer, the Erasmus Centre for Urban, Port & Transport Economics. “My research comprises four parts, which I completed one by one.” The first three parts deal with the question: How has the logistics system developed since the 1980s? “This includes such things as how national policy has promoted the position of the Netherlands as a European supply hub, for example by planning Maasvlakte 2 and the Betuwelijn, while leaving the development of logistics buildings to local municipalities and the market.”

Not the prettiest solution

In collaboration with Erasmus University Rotterdam, he took a close look at the employment opportunities these distribution centres offer. “For decades now, a main argument for developing logistics centres and infrastructure is that it creates jobs in the Netherlands.” Yet Nefs does not totally agree with this view. "Because of automation, new construction is actually creating fewer and fewer jobs per square metre. And the jobs that are created are often filled with foreign migrant workers because the centres do not match the regional labour market."

Another argument from developers is that logistics buildings encourage local ancillary activities, such as manufacturing. "But my research found no evidence of this effect. In fact, logistics regions often turn out to be vulnerable to the departure of industry and services." Added to this, the uncontrolled growth of storage and distribution facilities leads to more transport movements and thus more congestion and emission of pollutants. And the integration of logistics facilities in their surroundings is generally not the prettiest solution. “Is this really how you want to use the scarce land that is available? Despite the evident importance of logistics, the added value of many activities and square metres is limited. The Netherlands as a distribution country is only partially a success story.”

Can we do better?

Nefs feels that the tide is starting to turn. "Space is scarce, and becoming more so. That is why there is growing pressure to use it multifunctionally and intensively. For developers, the easiest and most advantageous option for the time being remains to build simple blocks, so governments have to intervene." Fortunately, the latter are increasingly stepping in to limit the construction of XXL centres to specific areas. They are also subjecting new developments to stricter requirements. “For example, they must have a favourable effect on the regional economy, be better integrated into the landscape, or install compulsory solar panels on the roof.”

That we can use these requirements to enhance the added value of centres without completely preventing their construction was recently demonstrated in Tilburg. Residents protested against plans for a logistics business park near the city, prompting the local government to impose much higher quality requirements. Companies wishing to establish themselves on the site must now demonstrably generate relevant jobs for the local population. In other words, more knowledge-intensive work and linkage with the manufacturing industry. Constructions must also meet high standards in terms of spatial quality, biodiversity, and architecture. A committee was appointed to assess companies' plans. The result? "Despite all these requirements, five times as many applications came in as fit the area! It is a clear sign that we can raise the bar in other places as well."

Location is key

The final component of his research addresses the question: how do you plan the logistics complex of the future? "We need to be circular by 2050, which means we will be doing a lot more repairing and refurbishing. The logistics complex has to facilitate this by housing the right processes in the right locations." Merten developed Grip, a new interactive map that scores every area in the Netherlands, including existing business parks, on usability for four logistics area types: (inter)national distribution, (re)manufacturing, materials and energy, and urban logistics.

The map takes 34 different factors into account. "For example, proximity to container terminals helps with international logistics, while proximity to consumers in turn makes sense for urban logistics." Merten gives an example of a striking conclusion: "What can cause problems, is that port locations are increasingly being transformed into residential areas nowadays. Think for example of Amsterdam, but also the Schiezone in Delft. Subsequently, those sites can no longer serve in a logistics network as, among others, circular construction hubs. So if we want to realise the circular economy, in some cases we have to be sparing of these gateways and hubs for materials."

Helpful tool

Grip is already being used by both provinces and the central government when planning new logistics clusters. Merten sent a questionnaire to 60 users for feedback, with the responses falling into two categories. "On average, central government employees found it very useful for discussing future plans, while those from provinces want a bit more flexibility, for example to consult with industry partners and developers. In such cases, it can actually be disruptive if the map does not endorse local ambition." Merten understands their concerns: "The map is just one of the tools available, not a final judgement."

Merten hopes his work will help to choose and use new sites in a smart way, and to use old sites as effectively as possible. "It should provide a basic overview for planners and policymakers and designers, hopefully they will be inspired." As a matter of fact, a follow-up project is already underway within the central government to elaborate on the four types of logistics and find out which design principles can be applied in each type. That fits with Merten's conclusion: "We need to move towards a new narrative of logistics in which we use our scarce space smartly and effectively to achieve a sustainable society."

This story is published in March 2022 and updated in May 2024.

More information

Merten Nefs will defend his PhD thesis 'Landscapes of trade: towards sustainable planning for the logistics complex in the Netherlands' on 21 May.

Merten Nefs is finishing his PhD part-time at TU Delft and is supervised by:

- Wil Zonneveld, professor of Urban and Regional Planning (department of Urbanism)

- Tom Daamen, Urban Development Management (department of Management in the Built Environment)

- Frank van Oort, Erasmus School of Economics

Merten also works at the Erasmus Centre for Urban, Port & Transport Economics.