Waiting lists. Treatment coming to an end. The closure of clinics. Our mental healthcare system needs help. How can a design approach help deliver better care. Delft Industrial Design Engineering researcher Nynke Tromp is examining the future of the mental healthcare system from within the Redesigning Psychiatry programme.

It all starts with the diagnosis. “People are assigned a DSM label based on questionnaires asking them about their symptoms”, explains Nynke Tromp. DSM stands for the ‘Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’. It’s the manual used to classify mental disorders. “Although there's some scientific basis for these diagnoses, the way we use them creates problems. You can't use a diagnosis obtained in this way to determine how to treat someone and what their chances of recovery are, while these are the most important functions of a diagnosis.”

“Our current system is based on the following medical model: you're ill, you get a diagnosis, you get treatment and then you should get better. The DSM label is largely responsible for determining the treatment options open to patients, and fixed number of minutes is allotted to each treatment”, continues Tromp. This leads to the over-treatment of people with less serious conditions and huge waiting lists for people with complex problems, who have great difficulty finding somewhere that will treat them, or who keep being given courses of treatment that are too short. Add in factors such as increasing demand for help because of an ageing, growing population, and it's not hard to see that the current system is under considerable strain and simply not sustainable. So what would work? Less regulatory pressure, less free-market competition and more room for custom-designed solutions: the call for change is coming from within the sector itself.

Vision for the future

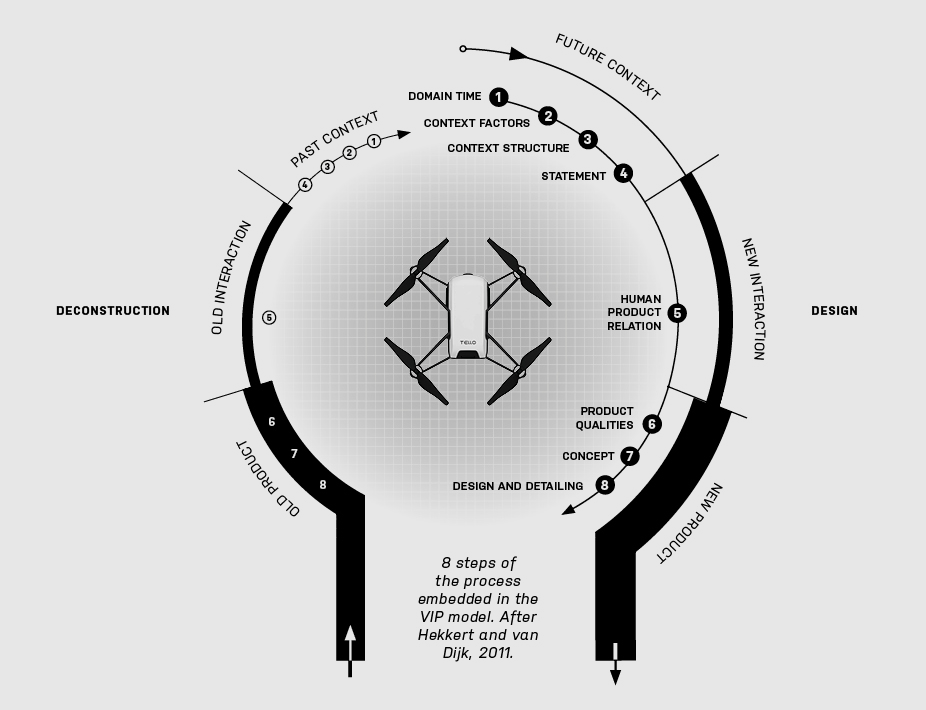

In the Redesigning Psychiatry programme, designers, philosophers, mental healthcare professionals and seasoned experts are working together to create a desirable vision for the future of the mental healthcare system in 2030, and to initiate steps towards this future. We're not talking about designing medical devices or equipment, but about innovation throughout the entire system. How can design help with this? The Vision in Product Design method, devised by Professor Paul Hekkert and Matthijs van Dijk from the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering, is not based on looking at the problems of today, but focuses on the possibilities for the future. “I carry out research into whether such a method is of value when you want to change a whole system like the ggz [the Dutch mental health care system]. Designers are good at imagining what things could be like and translating this potential future into something tangible for the outside world. The question is then how you deliver care in a future world. Or how should you deliver it? It’s also an ethical question. That’s why we work with philosophers and develop a framework so that we can design for the right values. Designers are continually thinking about the implications for people and society. We can translate this into concrete products and services: human-centered design is our strength.”

Vision in Product Design

In the ViP philosophy, designing entails responding to a future worldview, not reacting to the present. This means that a designer needs to take responsibility to shape such a worldview and take a stance on how to achieve change within this scope. This inadvertently requires some subjective judgment by the designer, and thus the authenticity of those choices is paramount.

Reframing Stigma

“To bring about fundamental changes, you have to be prepared to let go of the status quo and to provide a new target that everyone can aim for. This can be tricky, because everyone in the mental healthcare system encounters urgent problems. But using short-term fire-fighting will not enable you to radically change the system”, claims Tromp. “So it was particularly special that so many parties in the sector took part: mental healthcare organisations, patient associations, organisations assisted living. Even though nobody knew how it would turn out, everyone felt the need and had faith in the process. You also see that designers, being somewhat neutral in a field which consists mainly of psychiatrists and psychologists, are able to keep everyone on board.”

“We joined together to find ways of defining mental wellbeing and mental suffering, and explored how these new definitions could change the way we provide care”, explains Tromp. “How could we reframe our medical model? To put it simply, in the current situation, people are told that they have a disorder in their brain or their personality. This can sound quite frightening: words like schizophrenia or borderline personality disorder hardly encourage you to open up to others about your inner struggles. People are stigmatised by those around them, or they stigmatise themselves, and withdraw from society. The healthcare system itself often causes the negative impact, albeit unintentionally.”

Redesigning Psychiatry, on the other hand, sees mental health problems as interaction problems: “Obviously people have certain vulnerabilities. Certainly neurological and biological factors play a role, but whether a vulnerable person will be adversely affected by these factors also depends on the way they interact with their environment. Everyone has problems, feels down or irritable at times. You only need help when it becomes a pattern that you and the people around you cannot break”, explains Tromp. An important concept in this regard is the ‘problem-maintaining interaction pattern’.

“Take ADHD, for instance, a true phenomenon of our times. Of course there are internal processes that affect behaviour. But do we really consider someone who struggles with this to be sick? Or do we expect too much of primary school children these days, and that we judge certain behaviour to be ‘problem behaviour’ and label it abnormal?”, Tromp wonders. “If you see something like this as an interaction problem, it casts a different light on treatment. You're not so much treated for it, which is passive, but instead you look for strategies to help you alter certain types of interaction or break through it. The entire social system plays a role in this process.”

Ecological resilience

Resilience plays a key role in the vision. “Traditionally, this refers to your resilience as an individual in dealing with setbacks. But we view resilience in an ecological perspective. So it's not just about you as a person, but about your interaction with your physical and social environment and with yourself. How can you make that ecosystem resilient?” Unlike mechanical resilience, ecological resilience is not about restoring the equilibrium, but about adapting in order to thrive in a new context, in the same way as after a natural disaster. “We call this adapting or transforming, and this is different from stabilising. To achieve this you might even need to actively disrupt a system that makes you unhappy, rather like breaking off a bad relationship.”

Core tasks

Based on this concept of interaction patterns, Redesigning Psychiatry has defined three core tasks for the care system in 2030. “The first task is to help people to develop the skills they need to see for themselves where they are stuck in patterns that are harmful or that don't make them happy, and then work together to develop other patterns to replace them”, explains Tromp. “The second is to help people during transitions in their lives: moving into your own home, having a child, losing your job. Events like these put your ecosystem under pressure. It's important to be able to navigate your way through them and find a new balance that makes you happy.”

These first two core tasks revolve around prevention, in which the ambition is to help society as a whole to become more resilient. The third core task is to actively help people to break out of patterns. “Sometimes the heart of the problem is that they can't see how to do this, particularly if they are facing complex problems. You need experts who have the necessary knowledge about effective first steps”, says Tromp. “However, we can't construct a care system in which everyone can continuously receive specialist help. The ‘problem-maintaining interaction pattern’ model can help to differentiate when allocating care.” One of the next steps is to test whether this model can also actually solve the problems in the current system. “Care based on a ‘problem-maintaining interaction pattern’ model results in very different conversations with clients, and very different courses of treatment, with a greater focus on the social environment. We are already starting up some experiments on transitions.”

In addition, we're working on so-called process artefacts; resources that can help with the transition. “As a designer, you can also help to highlight the concept within a mental health organisation. That's what we're developing these artefacts for. For example, we're making videos to explain the vision, but also models which give tools to help put the vision into practice. We've developed a resilience field guide to help steer innovation, a manifesto that shows where we want to counteract developments in society. There's also a typology of organisational forms that helps you to explore how you could develop hybrid forms of care provision – from self-care, via peer-to-peer, to specialist care. You can download all these resources free of charge via www.redesigningpsychiatry.org/, because we do everything in open source”, she explains. “And if parties want to build or innovate something based on our vision, we will help them. By developing products and services which motivate changes in behaviour, you can already take steps in the right direction. We are operating at the intersection of design, behaviour change and transition management.

Convincing vision

The ultimate aim of the programme is to bring about a transition. “We've been working for five years now and we've noticed that the vision we've developed is still inspiring and convincing enough to persuade various parties to commit to the programme. From the transition management angle, this is one of most important steps for setting a transition in motion,” says claims Tromp. “But a transition of this magnitude takes time. Some organisations are in financial difficulty and can't afford to think as far ahead as 2030.” We also need to get the healthcare insurance companies on board.

System geek

Although Tromp is concerned about the state of the mental healthcare system, the transition process is her real passion. “This is an opportunity for me to examine the value of a design mindset in large-scale transitions. That is research through design, researching by actually doing something”, she explains. “I'm trying to understand this role, specifically the added value of design in complex transition issues. This is highly relevant because we currently need (or are undergoing) so many societal transitions. I'll be looking into the food system next, to see if there are ways of wasting less food on the one hand, and replacing animal-based proteins with plant-based proteins on the other. One day I'd like to tackle wildlife crime. When it comes down to it, I'm interested in any sector that needs a fundamental transition, whether it's people I can help, or animals or the planet.”