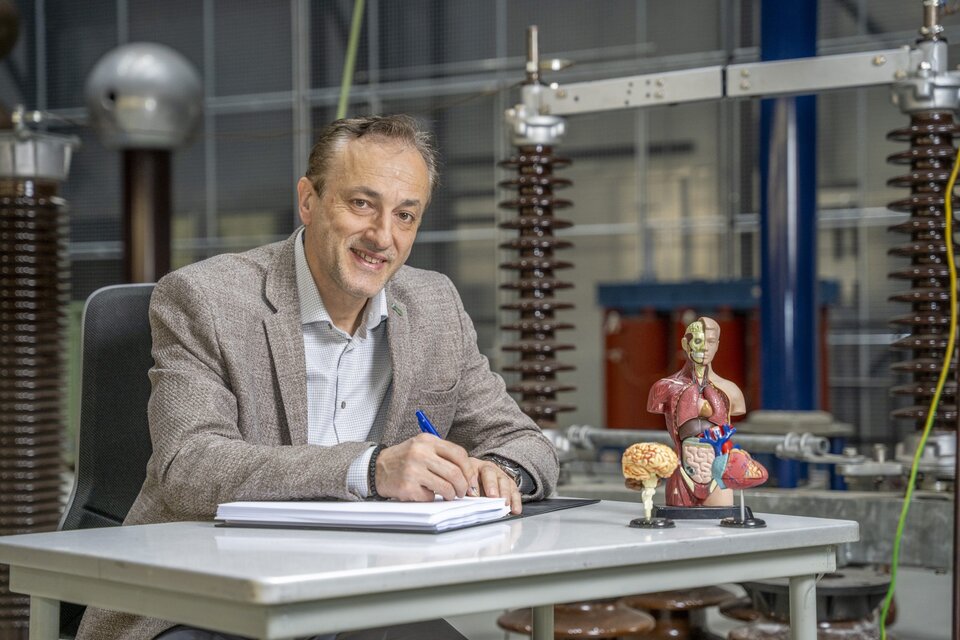

Fitting new infrastructure into our densely built-up country is becoming increasingly complex. The Integrated Infrastructure Design minor teaches students how to handle this complexity. “This helps us to train a completely different type of engineer,” says minor coordinator Hans de Boer.

Work to construct a new bicycle and pedestrian bridge over the Schie in Delft is expected to start in 2023. What’s special about this Gelatine Bridge? Students from the Integrated Infrastructure Design minor contributed to the design. “Streams of cyclists and pedestrians need to safely cross the bridge, but boats also need to pass underneath, and it needs to match its surroundings. And that’s where the tension lies,” explains Hans de Boer. “Students have studied the entire process and created various designs to explore which design works better from which perspectives. What is the best configuration, for example, and the best route?” The students worked under the guidance of Joris Smits, an experienced bridge designer. Preliminary studies such as this help project manager Anja Schmal and strategic advisor Jan Nederveen (from the Municipality of Delft) to formulate the Programme of Requirements for the tendering procedure.

The minor is the brainchild of DIMI: the Delft Deltas, Infrastructures & Mobility Initiative. Within DIMI, designers and researchers from disciplines including transport, water safety, urbanism, architecture and landscape design collaborate on integrated solutions. They aim to call time on a long-standing problem: the often laborious development and realisation of infrastructural projects. This is linked to the great technical complexity, the large investments and the impact on the surroundings. With regard to the third aspect, involved government bodies in particular are required to make political and administrative choices, which is a complex process in itself. “All things considered, it is becoming increasingly difficult to create infrastructure,” explains De Boer. “The Netherlands is a densely-populated country with relatively little available space, and with already highly-developed infrastructure, so it is difficult to fit something new in. Maintenance and the necessary budget for this also needs to be considered.”

The changing role of the government also plays a role. “A lot is left to the market, so it has to take a different approach. But commissioning also means that government organisations require expertise. How can you otherwise determine whether your tender was up to scratch? And are you capable of assessing whether a certain quote or design is suitable?” Once laid, there is usually no way back. “Infrastructure needs to last 50, 100 or even 200 years. Take railways or waterways, for example. If they are poorly executed, there is little you can do. But if it’s done well, there are social and economic rewards to be reaped. So your designs need to be future-proof,” says De Boer.

If plans for a road have been drawn up and the required ground has been acquired, there’s hardly anything you can do if you run into a problem.

Designing research offers a solution: “Design is all about adding, changing and making things possible. At DIMI, this design process is key when examining the issues in a specific environment,” explains De Boer. “It also helps you to avoid missing opportunities. If plans for a road have been drawn up and the required ground has been acquired, there’s hardly anything you can do if you run into a problem. In the preliminary phase, in a manner of speaking, it only takes a dash of a pen to bend a straight line.”

That is at odds with the traditional method, where concept, plan, discussion, decision, design, applying for permits and execution follow one after the other. “A sequential process like that can take up to ten years, and anything can happen in the meantime,” explains De Boer. “On top of that, those who become involved further down the line are presented with a finished product. If it only then becomes apparent that, for example, the expertise on ventilation in a tunnel was not incorporated in the design on time, there’s no way back. So let’s bring all involved disciplines together in the preliminary phase. This will help us understand the challenges that lie ahead and the conditions, so that some of the problems can be avoided.”

We work together with municipalities and the province on topical projects that are still in the exploratory phase.

Wide applause

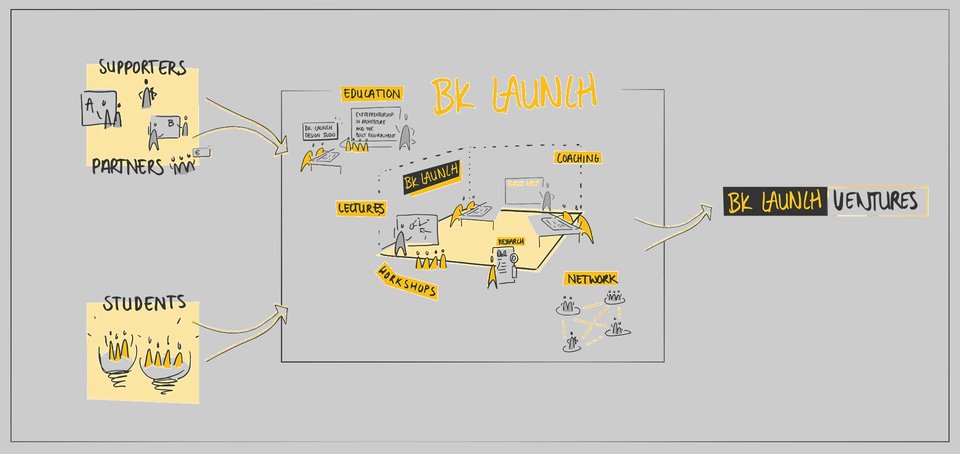

In recent years, DIMI has focused on designing research as a scientific approach; this expertise is being incorporated into the curriculum for the Integrated Infrastructure Design minor. Students from various design and technical disciplines spend a semester working on design cases for concrete infrastructural problems. The design of the minor was widely applauded. Alumnus and urbanism expert Marcel Smeets, the Second Flemish Government Architect (2005-2010), called TU Delft ‘the only university, within Europe at least, that is in the position to use its own portfolio to launch a programme such as this’. DIMI’s advisory council, which includes building contractors such as BAM, engineering firms such as Royal HaskoningDHV and dredgers such as Van Oort, as well as the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management and the Board of Government Advisors, were equally enthusiastic. De Boer: “This perfectly matched their call for graduates who are also able to look beyond their own discipline.”

The minor was introduced in the 2015-2016 academic year. “It is a unique programme with coordinated subjects in light of the scope of the projects and the knowledge required from various disciplines. We work together with municipalities such as Delft and Rotterdam and the Province of Zuid-Holland on topical assignments that are still in the exploratory phase. The character and status of these assignments means that they are not ready to be presented to an engineering firm, but they are ideal for designing research studies,” says De Boer. Students first learn the basics: the analysis skills, design skills and ways of thinking associated with the various disciplines. “Urbanism, landscape design, architecture, civil engineering and technology, policy and management: we unite all of these perspectives in the various subjects. How do you go about designing a bridge or road, and how do you incorporate it in the landscape? Do you need two quadruple lanes for the new road, or can we look to network or system level for an alternative solution? And if the road creates a barrier between districts, how do you restore the connection? We present students with practical scenarios such as this.”

Final assignment

These are all preliminary exercises leading up to the final assignment, which every team is required to complete successfully. “The final assignments are in Rotterdam. We’ve worked on several assignments for Feijenoord City, a large area development programme close to the new station. The Erasmusbrug and the Willemsbrug are already overburdened, so a third river crossing needs to be built in the area. The concept designed by the students last year has been included in the City of Rotterdam’s ‘bridge studio’, and is being considered as a serious contender. These are third-year students!”

The proposal for a new stadium in the Kop van Feijenoord also proved a success. The station needs to become part of the light-rail connection set to run between Leiden and Dordrecht, via the so-called Oude Lijn. Based on their analysis, one of the teams concluded that there was a transport void on the Noordereiland, near the Entrepotgebouw. They thought that this would be the logical location for a local station instead of Rotterdam Zuid station, as a new station is already being built for Feijenoord City further down the line,” says De Boer. “Plans have now been drawn up for the Oude Lijn, and their Entrepotstation has been included. The municipal engineering firm has also completed a feasibility study examining the cost of this underground station. This is a fine example of the social contribution that you can make, and the impact you can have, as a minor student.”

Terbregseplein

The 2021 edition of the minor focused on Feijenoord City and the area between Kralingsezoom and the Terbregseplein. “That is part of the Rotterdam Residential Vision 2040. Ten to fifteen thousand homes need to be built in the area. Under the supervision of Marc Verheijen and Wouter Kamphuis from the City of Rotterdam’s engineering department, we used various sub-projects to explore how we could use a combination of high-quality public transport, architecture and urbanism to address the issues associated with living close to a motorway: emissions and noise nuisance, for example. You also need to take into account that from 2040, the percentage of electric vehicles on the roads will be considerable.” This year, students have therefore once again been able to sink their teeth into a series of challenging interconnected design assignments, so that they need to consult not only with their own team, but also with other teams.

In addition to design expertise, the minor also addresses other skills. Soft skills such as presentation and consultation, and writing an essay on a piece of infrastructure that intrigues them. Students also have to learn to put themselves in the shoes of various parties. “I love seeing how students come to realise that they see the world from their own discipline, and that other disciplines have different perspectives.” He continues: “Administrators, users and builders all experience a piece of infrastructure in their own way. The builder’s aim is realisation, the administrator wants to achieve objectives such as improved access or increased economic activity. The user perhaps also wants better access, but not with a motorway in their backyard. You have to learn to keep all of these perspectives in mind.”

All hands on deck

“All things considered, it’s a packed programme,” notes De Boer. “Students earn 30 credits with the minor, but it’s a full-time commitment for nearly six months. Experts from the field visit to share their stories and supervise students. The minor involves a lot of group work. Students have to plan, assign tasks, make schedules, develop arguments, communicate and draft a business case. As a student, you cannot get much closer to the professional field, but it is all hands on deck.” And that means that the odd grumble can sometimes be heard. “The occasional battle of wits, or a group hug; such dynamics are important. And at the end of the course, they are surprised at what they have achieved. Before they started, they never would have thought it possible. So it is very rewarding work.”

With thanks to...

The minor was established by a group of eminent professors, including landscape architect Dirk Sijmons, urbanist Han Meijer, architect Michiel Riedijk, architectural engineer Jan Rots, integrated designer Marcel Hertogh and structural designer Rob Nijsse. Day-to-day affairs are dealt with by Joris Smits, René van der Velde, Filip Geerts and Marco Lub from the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, together with John Baggen and Mark Voorendt from Civil Engineering and Geosciences.