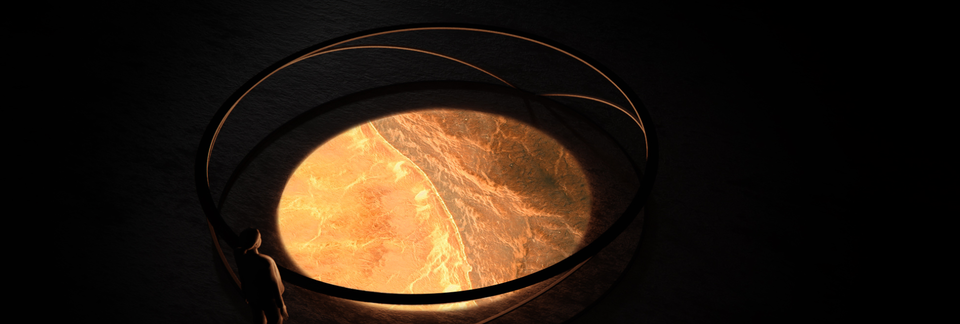

The Sand Motor, the Marker Wadden, the reinforcement of the Houtribdijk: the Netherlands is leading the way in building with nature. Matthieu de Schipper and Anne Ton investigate what happens at the point where the water meets the land, discovering new worlds in the process.

“A bare expanse with no vegetation or birds”, says Anne Ton, remembering her first field trip to the Marker Wadden. She had to wear a helmet because officially, it was still a building site. Since then, the nature reserve created with sand and silt from the Markermeer has become completely covered with vegetation and is a breeding ground for all kinds of bird species, some of which had not been seen in our country for decades. “The landscape changes from one day to the next, fascinating.” Ton has been studying the currents around the Marker Wadden and the sand reinforcement of the Houtribdijk. “We are discovering new worlds. Literally, as in worlds that were not there before but also in the sense that we are measuring and mapping existing phenomena for the first time.”

Matthieu de Schipper shares this fascination for the changing shore. Over the last few years, he was often to be found at the Sand Motor, the man-made peninsula that reinforces the coast of South Holland. “Wind, waves and currents have free rein so if you haven’t been there for a month, so much will have changed”, he says. “Quite exciting, because what exactly has happened? And might intervention be needed in order to ensure that it’s still there later on? You have to enjoy getting to the bottom of such things.”

Fieldwork is sometimes hard

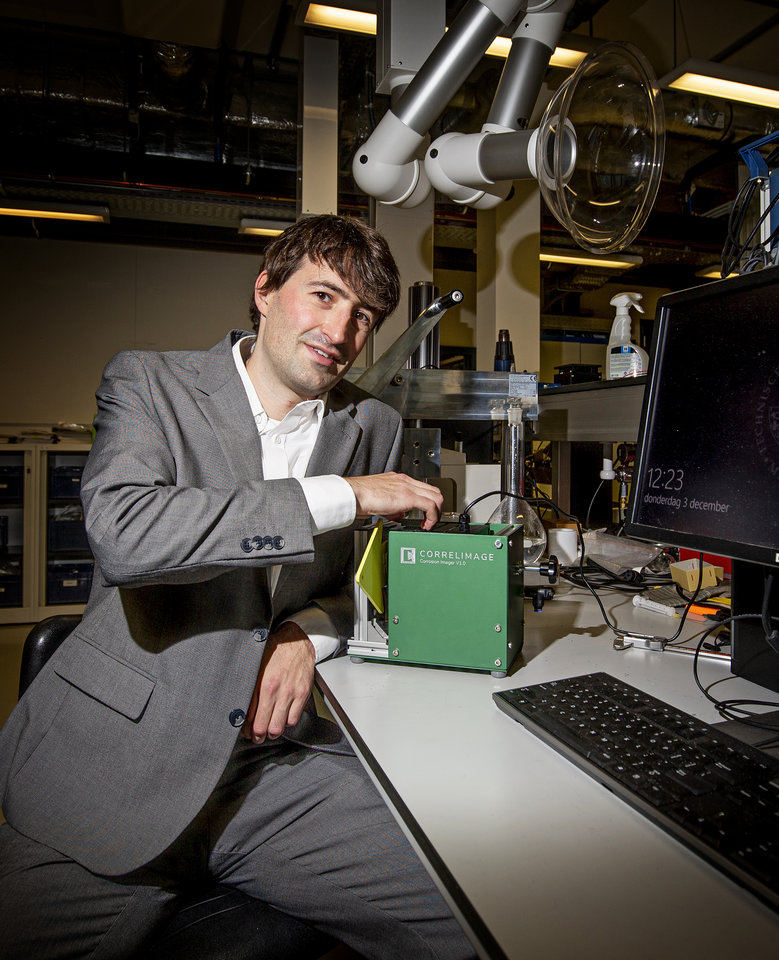

It means a lot of fieldwork and a great deal of pioneering. “We carry out measurements in order to find out how currents and waves move the sand but there is no standard equipment for doing that. So we often really put available equipment to the test, or come up with something ourselves”, says De Schipper. His prime example as far as this is concerned is Walter Munk, known as the Einstein of the ocean: “In the 1950s, he discovered how waves move between Antarctica and Northern Europe. He did that using huge machines that produced printouts equivalent to seismic vibrations. That was just possible back then.” De Schipper is grateful to be able to use inexpensive modern electronics. “These days, it is so cheap to equip floats with GPS in order to carry out bottom surveys that you can use 20 where previously it was one.”

However such equipment has to be quite robust. Just like the field workers themselves: “When you are planning a measurement campaign, you don’t know whether you are going to have icicles hanging from your nose the same time next year”, says De Schipper. Ton can identify with that: “I often go into the water myself so if the waves are too high, you have to reschedule anyway.”

They don’t mind putting up with the occasional hardship. During their time at university, both were captivated by the question as to how coasts are formed. “To start with, I was really excited about big hydraulic engineering projects like bridges and dams. Then I discovered coastal engineering and the principles of how sand and water move”, says De Schipper. The subject has never left him; nowadays, it is he who inspires new generations – including Ton – as an associate professor: “Matthieu was one of the coastal engineering lecturers who spoke passionately about their work. Wow, this is what I want to be doing, was my reaction.” They observe that same light-bulb moment with their current students. De Schipper: “When carrying out fieldwork, you see the coast inspire wonder in them: hey, this is cool. That is really motivating.”

When carrying out fieldwork, you see the coast inspire wonder in students: hey, this is cool.

How coastal interventions are incorporated in the natural system is one of the key questions in De Schipper’s research. “When a beach or shoreline is widened to provide better flood protection, we want to know how the sand is going to be dispersed. By investigating this in different places, we can get an increasingly better picture of that and subsequently design engineering interventions in such a way that we get maximum benefit from them, in terms of safety but also ecology and recreation.” With its lee zones, the Sand Motor attracts shorebirds, bottom dwellers and fish and also a lot of human visitors.

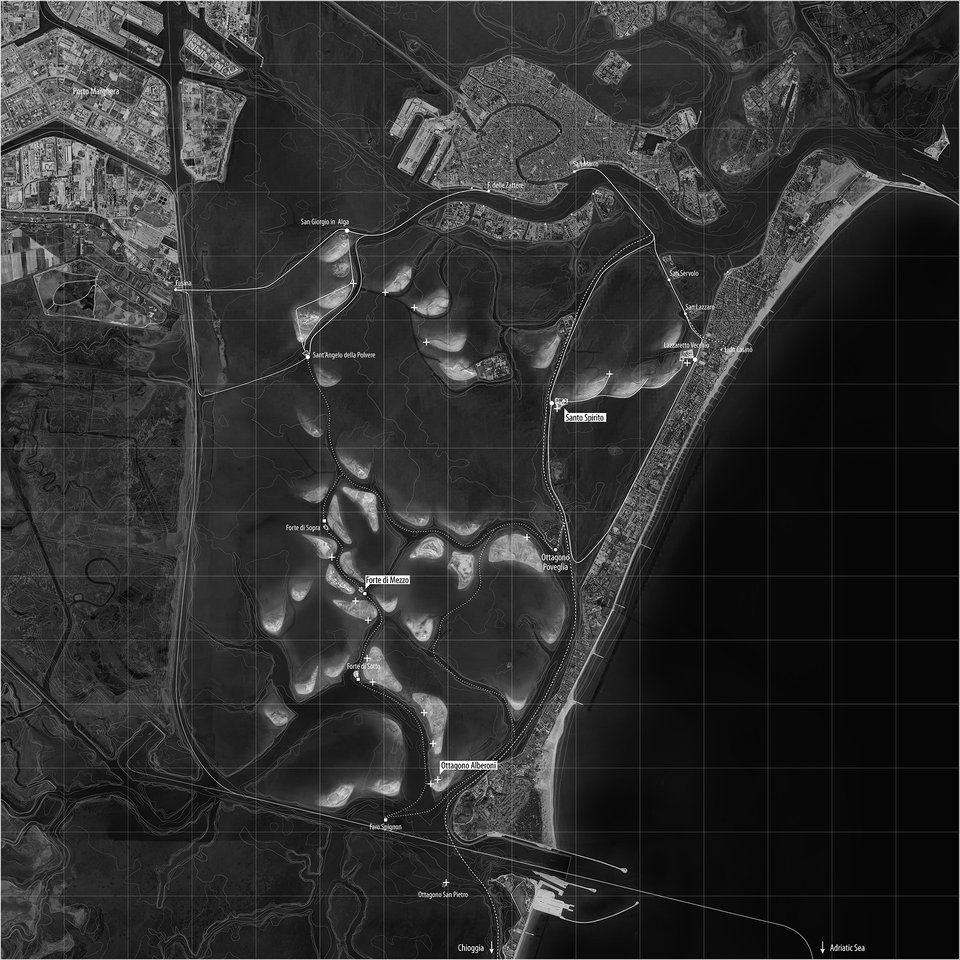

Ecology has also played a major role in the reinforcement of the Houtribdijk, once built in order to reclaim land in what is now the Markermeer. “That didn’t go ahead but without a supply of fresh water, it left a relatively dead lake”, says Ton. When the Houtribdijk had to be reinforced a few years ago, it was decided that it would be done in a ‘soft’ manner. Wide shorelines were created using sand from the lake itself; the silt that was released during sand extraction was used to create a nature reserve. This is the Trintelzand reserve with sandbanks, shallows and wetlands. “It is nature that’s man-made but for the already unnatural Markermeer, it’s quite an upgrade.”

We are discovering new worlds. Literally, as in worlds that were not there before but also in the sense that we are measuring and mapping existing phenomena for the first time.

To maintain it, it is important to have a good understanding of the new area. “We found out that currents all over the lake influence the beaches along the dike. So for the safety of the dike beyond, you have to zoom out and monitor the whole system”, says Ton. “We therefore measured waves and currents on both sides of the dike among other things.”

Beaches on a lake with no tide are scientifically virgin territory anyway. “It is a bit of a niche subject. But now I know that there are a lot of similarities with so-called low-energy beaches which they are doing research on in Australia, for example. There they are now also very interested in how our Markermeer beaches have developed. In fact until recently, very little was known about them.”

Satellite observations

New technology offers new opportunities for this. “We visited the Marker Wadden every three months. You’re happy when you have got all the measurements done”, says Ton. “One of my students works with satellite images and provided photos of the whole island every two weeks. You can’t see any water depths on them but you can see the waterline. That’s valuable information that you can obtain with relatively little effort.” Over the next few years, the field will expand a lot further in this way, predicts De Schipper. “We now mainly have information on coasts that we can easily get to ourselves. With the emergence of satellite observations, we will soon be able to view extremely large areas at a time, as well as remote regions or ones that are difficult to measure. When combined with tools such as machine learning, that could usher in a whole new bloom period.”

There’s one big unknown that De Schipper still wants to resolve: “Every day, huge quantities of sand move offshore. Sand that is just below the water slowly creeps up the beach or sinks back down slowly. We already know some basic principles. Large replenishments or such a new beach are examples of what they call manipulative experiments in ecology. We disrupt the natural balance slightly in order to see what happens”, he explains. For his dream experiment, he would deposit sand that was labelled in some way along hundreds of metres of coast. “That way, we would be able to track that sand at grain level so we could see exactly where the sand that we deposit ends up and the associated timescale.”

That knowledge is important as coastal maintenance solutions are still being proposed based on experience. “We see that something works globally but we can’t carry out precise calculations for it yet. With numerical models, we would be able to carry out projects of this type in different parts of the world much more easily.”

Soft versus hard

So building with nature as an export product, as it is already being carried out successfully. Yet there is one aspect of this typically Dutch approach that is met with criticism at times. “Ecologists abroad sometimes consider it impertinent how we create nature in the Netherlands. That it's not right”, says De Schipper. “Personally, I think this ability to produce something is beautiful. And what is real nature anyway?” Ton: “The combination of building materials and nature is interesting and they can even reinforce each other. Just look at how ecology has developed at the Houtribdijk.” Besides opportunities to make the coastline more ecologically diverse, there is another long-term benefit. De Schipper: “The raising of dikes involves high costs and emissions. Softer solutions are much easier to adapt to changing conditions such as rising sea levels or new ecological insights.” And that is a major benefit in these times of climatological uncertainty.