Zuidwijk, technician at the Optics Research Group of the TU Delft: “When I was 21, I seriously considered studying history. The interest runs in the family. Eventually, I stuck with technology and studied material science, which in retrospect is also a kind of history”. Combining his passion for history and science he developed the exhibition ‘Optics for all’, in collaboration with The Academic Heritage Team of the TU Delft Library. The exhibition is currently shown in the TU Delft Science Centre and can be visited until January 31st, 2020.

Optics is for everybody

Two years ago, in celebration of their 70th anniversary, the optics department had their first symposium ‘Face2phase’ . In preparation Zuidwijk and Joseph Braat, retired professor in geometrical optics, dove deeper into the history of the department. Two years later, they are back again. This time exhibiting their findings about the works of professor Bram van Heel who founded the department. Braat was the last graduate of Van Heel: “Simply because of my age, I studied briefly under Van Heel”

In the exhibition you can find the personal work of Van Heel, his practical methods, and optical instruments from around the time just after the Second World War. Part of which was made by the department in their lens polishing workshop that has now been relocated to TNO. Zuidwijk: “Optics used to be quite mathematical, and the Netherlands had little practical knowledge. What Van Heel tried to do is make the field more accessible, not only for industry but also for a larger audience, which is why the exhibition is called Optics for all. Funny actually, I just realised, this is exactly what we are doing.”

The Exhibition

Professor Van Heel

Van Heel was the founding father of Technical Optics in the Netherlands. In 1947, he founded the optics department at the TU Delft. In collaboration with many of his students, he managed to turn complicated theories into applicable methods, allowing the industry to design advanced optical systems. His alignment method, shown in the science centre, is one example of how he used theoretical phenomena to develop ‘simple’, practical, and precise optical methods. For instance, his method of alignment, which was mostly used when construction over large distances was required.

His method of alignment

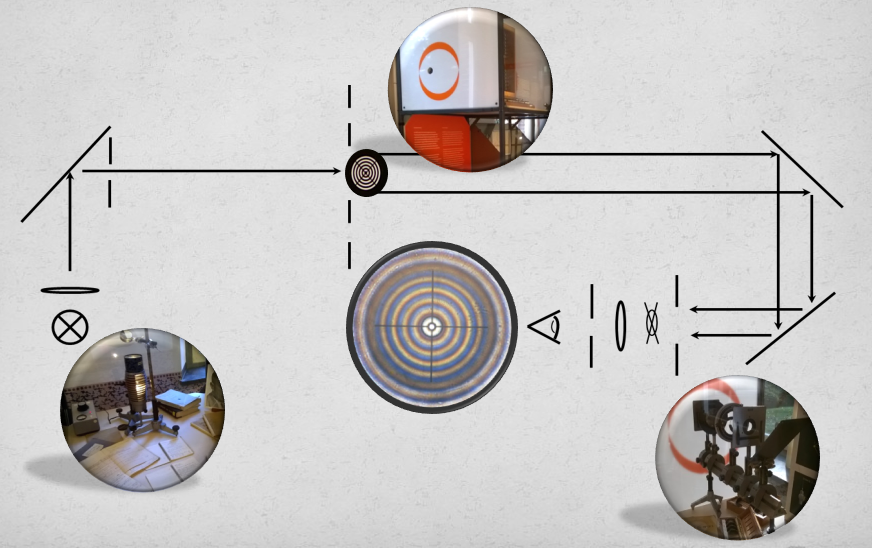

After the second world war, this method was used to repair damaged bridges more efficiently by allowing reconstruction to occur from both sides simultaneously. Instead of using mechanical methods, such as long cables, where the accuracy is tainted by the presence of gravity, Van Heel designed an optical alignment method that does not encounter the aberrations (deviations caused by lenses) commonly found in optical methods.

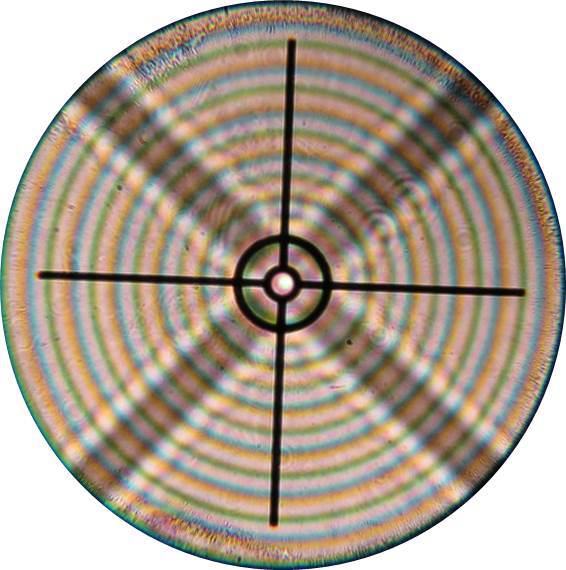

Inspired by Young’s double slit experiment, Van Heel used a plate with concentric circles, also known as a Zone plate, to align three points with respect to each other, thus forming a straight line. When aligning the two sides of a bridge, all that is needed is a bundled light source at one side of the bridge, a pinhole with a target at the other side, and a Zone plate in between the two ends. These Zone plates are basically circular bars that create an interference pattern, which allows for the very precise alignment (in the order of 10-20 micron at a measuring distance of tens of metres) in both the horizontal and vertical directions. When a light bundle shines straight onto the Zone plate, these two points are aligned, and the rays form a circular interference pattern that you can see when you look through the pinhole. When the target of the pinhole is in the middle of these circles, all three points are aligned.

The lost history

“It was rumoured that there was a personal archive of Van Heel somewhere, but nobody knew where it was. Maybe his family had it or it was lost during a move,” Zuidwijk says. To make a long story short, he adds, “a week before the material of the exhibition had to go to the printer’s, the archive was found in the filing cabinet of professor Braat”. It had been there since before his time. Luckily the department rarely moved location, leaving most of the archive in its place.

Optics pioneers

During their research into the archive of Van Heel, they came across many incredible stories about the pioneers in the field of optics in the Netherlands. Besides Van Heel’s personal work, his archive contained books of Caroline Bleeker, or Lili amongst friends. “She was the founder of the first optical industry in the Netherlands, eventually taken over by the ‘The Old Delft”, Zuidwijk says. “Which is impressive for a woman in that time, setting up such an enormous industry. Reading her story is really exciting”. She built optical equipment in her instrument factory in Utrecht, which at the time contained just a single drill and lathe. Later in her career, she worked together with Frits Zernike and was the first in the world to build his phase contrast microscopes.

“There is however so much more that happened around that time”, Zuidwijk says. “Oscar van Leer together with Van Heel started ‘Van Leer’s optical industry’ just before the war. Which later became ‘The Old Delft’, famous for their microscopes”. Van Leer was also the first to develop the ‘Sound Film’. Movies at that time used to be silent, with a pianist sitting beside it playing the music. Van Leer was the one to put the two together on one tape. “That was special at that time, just before the war”, he explains.

Back to the future

With all this newfound material, Zuidwijk is looking into the possibility of another exhibition. Although methods are no longer used as they were designed, their principles are still the same. And many of the companies that were founded are still of relevance, not only here in Delft, but also in the rest of the world. “Maybe in three years, when we have our 75th anniversary, we can cover all of the department’s history, the professors, and topics from the past 75 years.”

From left to right: Marcel Janssen, Jules Schoonman, Hans Kaiser (all TU Delft Library) en Thim Zuidwijk (Applied Sciences)

Photo's: Johannes Schwartz