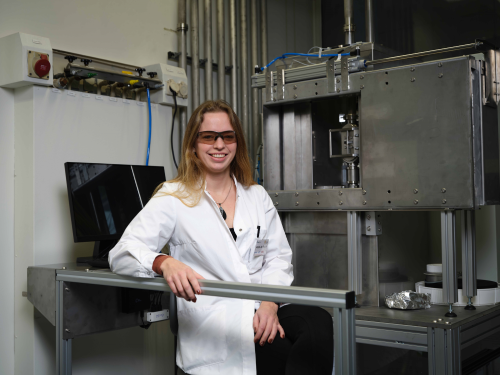

When residents feel connected with their neighbourhood, they feel more responsible for creating a pleasant atmosphere. But how do people connect with their living environment and how can you support that process? This is what Geertje Slingerland is researching: "I find it fascinating how people live together in the city and would like to establish a dialogue between policy makers and residents in order to create a pleasant living environment."

Heart for the neighbourhood

"If residents have a say in what their neighbourhood looks like, they will feel more connected to it and take better care of it," says Slingerland. "By letting them think along and giving them some control over their living environment, you can make a neighbourhood a lot more liveable." In her research, she looked at how people connect physically and socially with their environment. She also took into account the role of institutions involved in the living environment, such as a municipality. "For a local government, for example, it is important to have an eye for groups of residents who are not at the forefront when a residents' meeting is organised to make an inventory of wishes for the neighbourhood."

The Hague Story

Using various, sometimes already existing, initiatives, Slingerland analysed what factors play a role when making a connection with your neighbourhood. The already existing initiative The Hague Story ('Haags Verhaal') has been an important source for gaining more insight into the social connecting aspect. The 'Haags Verhaal' brings together different communities that share something in common, but would nevertheless never meet spontaneously, for example because they live in different parts of the city. Think of a common hobby, such as cooking or a religious background. During such an evening of stories, one person from each group tells his or her life story from the perspective of their own community to a group of about 70-100 people. This is followed by a discussion with the audience about differences and similarities in views.

Social connection

"The great thing is that you then look at your surroundings from someone else's perspective. It is a good way to establish new social connections and to better understand each other's point of view. It creates social bonds, and because you empathise with the storyteller you also learn more about the place you live in." This is clear from the interviews Slingerland conducted afterwards among the audience, the storytellers and with the organisation of this initiative. "An eye-opener for me, but also for the organisation, was that you have to talk about the differences of opinion, and not be afraid to discuss them. It is precisely where things falter, where people do not agree with each other, that there is much to be gained. This will lead to a real connection based on mutual understanding, empathy and appreciation. It is a good basis for developing something together. For example, a real estate society and the homeless foundation subsequently entered into a dialogue to see how they could help each other further."

Framework

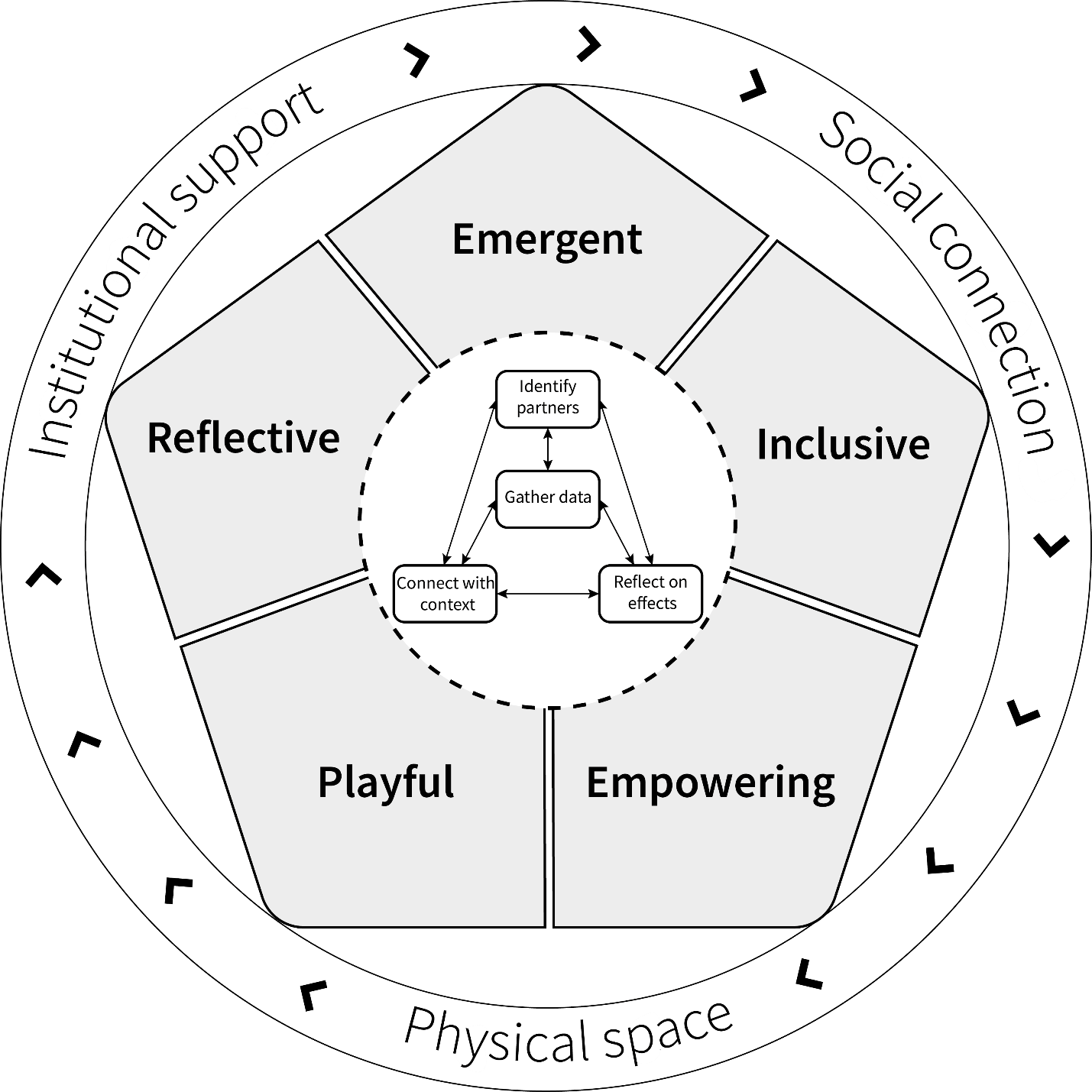

Slingerland made a framework based on the story initiative and other initiatives, with recommendations for reflection and discussion for such meetings to support the participatory design process. The framework shows how people can connect with their living environment on the basis of five design principles and four activities.

Confidence-building

Before entering the research trajectory, it is very important to become familiar with the local context. "And that takes a considerable investment of time," Slingerland experienced. "It doesn't work if you arrive as an outsider with your surveys and ask residents, without them knowing you, to give you their vision of their living environment. They have to get to know you first, a bond of trust has to be established, and only then you can really get going with your research." Slingerland therefore spent a lot of time in community centres where people from different walks of life come together. It took a total of two years before she could go into depth. The arrival of the corona virus was also a delaying and limiting factor.

Impact of corona

The planned 'live' workshops in the youth centre were first put on hold, and later given shape via a hybrid construction, but unfortunately it did not work out as hoped and Slingerland had to let this project rest. "A great pity, of course. Corona really had a big impact on the existing social structures, especially during the first lockdown, when everything had to be closed down. People could no longer meet each other, find each other nor help each other. That became painfully clear. Years of built-up relationships between youth workers and young people were diluted in a matter of months, because the youth centres did not have digital tools at their disposal or staff members lacked the skills to use them."

Reflection

Still, not everything has been in vain. A PhD student at Eindhoven University of Technology, with whom Slingerland was to organise the workshops, is now using the failure of the project as input for her PhD research. "Reflection on this process is also very instructive. We are now writing an article together about why it went wrong. In any case, it is clear that it is very important to invest in ways in which people can meet each other in order to prevent people from missing out on social connection. We are also looking at the role of municipalities in this." Another project, a summer school in Ireland, in which young people got to work on a digital artwork about their community, again had to take place entirely online due to the coronavirus. Fortunately, this project was successful, thanks in part to her Irish counterpart, who supervised the young people in Ireland. Although corona threw a spanner in the works, it also gave Slingerland new skills in digital research methods.

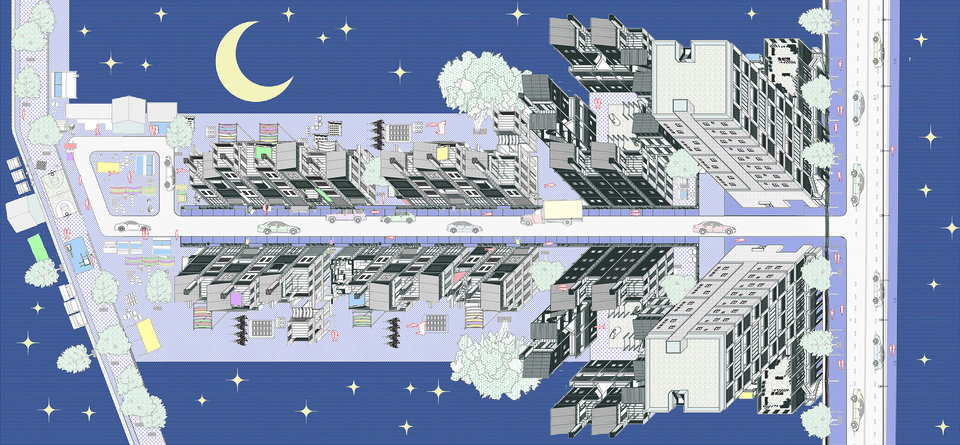

Digital game

Slingerland is originally an industrial designer and likes to immerse herself in interactions in the design process. "I like to use creative processes to make people think about each other and their environment and then study how you can influence this." In her research, she has also worked with children in the game 'Secrets of the South' that was co-developed by researcher Xavier Fonseca at TU Delft at the time. The aim of this digital game is twofold: on the one hand, to give people from different ethnic backgrounds opportunities to connect with each other by breaking down social barriers and, on the other, to let them explore their own neighbourhood so that they feel at home. Fonseca focused more on the social connections and Slingerland on connecting the child with the environment. "I found it quite exciting to work with children, it was a new target group for me. In retrospect, it was also one of the most enjoyable research projects I have done and one I am quite proud of."

Connection to the world of experience

"It was especially fun to let the children think up their own challenges so that they could get to know their neighbourhood better. You immediately observe what they find important and can respond to that. I have noticed that it is very important to let them participate in the assignments of the game. To see from their perspective how they connect with their environment. In this way, the game fits in best with their perception of the world, they start playing it enthusiastically and subsequently get to know their neighbourhood better," says Slingerland. A metro line runs through the Tarwewijk district of Rotterdam where she carried out her research. It is characteristic of the neighbourhood. "One of the challenges that the children came up with was to run faster than the metro. An important play area for the children in the neighbourhood is a place where waste containers are located. All sorts of challenges were devised around it, such as: find five more rubbish containers in the area. All these challenges were incorporated into the game. The children then chose which challenge they wanted to play.” Afterwards, she asked them what they had learned from it. It turned out that the children got to know their neighbourhood better and were more proud of it. And they learned new things, such as that many people in their community do not speak Dutch and how to deal with that.

Dialogue

There is a lot of movement going on in the field of inclusive participation processes. How to give residents and other stakeholders a voice in policy, for example in the Participative Value Evaluation (PVE) method of TPM researcher Niek Mouter. Slingerland: "The difference with the framework I set up is that a real dialogue is initiated between the decision-maker and the resident. A decision-maker cannot simply set aside an opinion. At the same time, this can also feel threatening. Governments often find it risky to give away a bit of responsibility. They are often wary of the unpredictable, afraid that residents will come up with unrealistic ideas. Slingerland thinks this fear is unfounded, especially if you provide guidelines. "I want to call on them to give residents' initiatives a chance and to enter the design process openly. Dare to let go! When residents are able to influence their living environment, the bond with it improves. And that makes for a nicer, more liveable neighbourhood."

The Participatory Place-making framework

The Participatory Place-making framework proposes five design principles: empowering, inclusive, reflective, playful and emergent. Researchers and designers can use these principles in devising and developing urban interventions that aim to strengthen residents' connection with their neighbourhood. The framework also suggests four activities that designers and researchers can carry out together with residents and other stakeholders to conceive, implement, and evaluate the intervention. This results in an intervention that fits the neighbourhood in which it is implemented.