When you build in an earthquake-prone region, your structure should be resistant. Sounds reasonable, but merely making shock-proof buildings is not enough, according to Dr. Simona Bianchi. She leads a team performing multi-hazard analysis. “An earthquake often leads to other disasters, such as fires or floods. If you want to protect people and property, you have to design with these risks in mind.”

Simona’s current work is incredibly varied. She heads an international team of researchers designing modular, sustainable, and multi-hazard-resistant structures. Not just that, Simona is also working on renovation procedures for existing buildings. Her current tasks are incorporating climate uncertainty in analyses, and developing technologies to aid post-disaster recovery. But as a researcher, her origins lie firmly in the study of earthquake damage. Simona: “I still think that many useful lessons could be learned by building a model of an entire city on a shake table.”

How to become a disaster scientist

Simona grew up in central Italy, a region which is unfortunately all too familiar with earthquakes. “From a very young age I was already aware of the danger.” She first encountered the scientific study of earthquakes in high school curriculum. During the course ‘astronomic geography’ she was taught physics related to the entire earth, including the movement of tectonic plates. “There were multiple lectures about the generation and propagation of earthquakes; not surprising given Italy’s geography and history.”

From a very young age, I was already aware of the danger of earthquakes.

On 6 April 2009, Simona was in her home town when she felt the tremors of an earthquake. On the radio, she heard that the nearby city of L’Aquila was badly hit. Simona: “My brother was living in L’Aquila at the time. My mother and I tried to reach him for the entire night… We only found out that he was okay the next morning. He was lucky that he was outside the city centre, which completely collapsed.” Both old masonry and new reinforced concrete failed. Many inhabitants were injured, more than 300 even lost their lives. If Simona Bianchi was already headed towards earthquake research, this experience crystallized her ambition.

That same summer, 2009, Simona finished high school and moved to Rome to study Civil Engineering. Her MSc graduation project was a case study on L’Aquila: an economic analysis of earthquake damage and of retrofitting scenarios. She won a scholarship to study at the world-renowned earthquakes study centre in Christchurch, New Zealand. Returning to Italy afterwards for her PhD, Simona took about 30 students to visit L’Aquila every year. At first they mostly studied the damage, as much of the centre still lay in ruin. But later, her students designed renovation practices to increase earthquake resistance of existing buildings. And when another earthquake struck central Italy, Simona and her professor organised a collegial site visit with the same goals: cataloguing the damage and suggesting renovations for nearby structures.

A PhD that just keeps growing

Simona's PhD focused on the resilience to earthquakes of ‘connecting elements’. Think of joints between beams and columns, or attachments of walls to the foundation. “The majority of earthquakes are low intensity. In these cases, the building’s structural skeleton usually remains intact. Attached to this skeleton are the non-structural elements, which are more easily damaged. These elements include facades, partitions, ceilings, but also services like air conditioning, heating, furniture...” Optimising the connecting elements can ensure that the building remains functional after an earthquake, which is especially important for vital services like hospitals or power stations.

The PhD started small-scale, but soon Simona got permission to build 1:2 scale models on shake tables. Here she discovered the importance of an integrated approach and started to study not just connectors, but every aspect of earthquake-resistant structures. For example, she incorporated sustainability by testing timber constructions, lightweight facades, and biobased fibres. And she designed modular structures, which means construction, repair, and end-of-life treatment all take less energy and materials. Thus, as with her site visits, Simona’s research got progressively more ambitious.

What it looks like to build 1:2 models of structures on a shake table. Video courtesy of Simona Bianchi.

Misunderstandings about disaster research

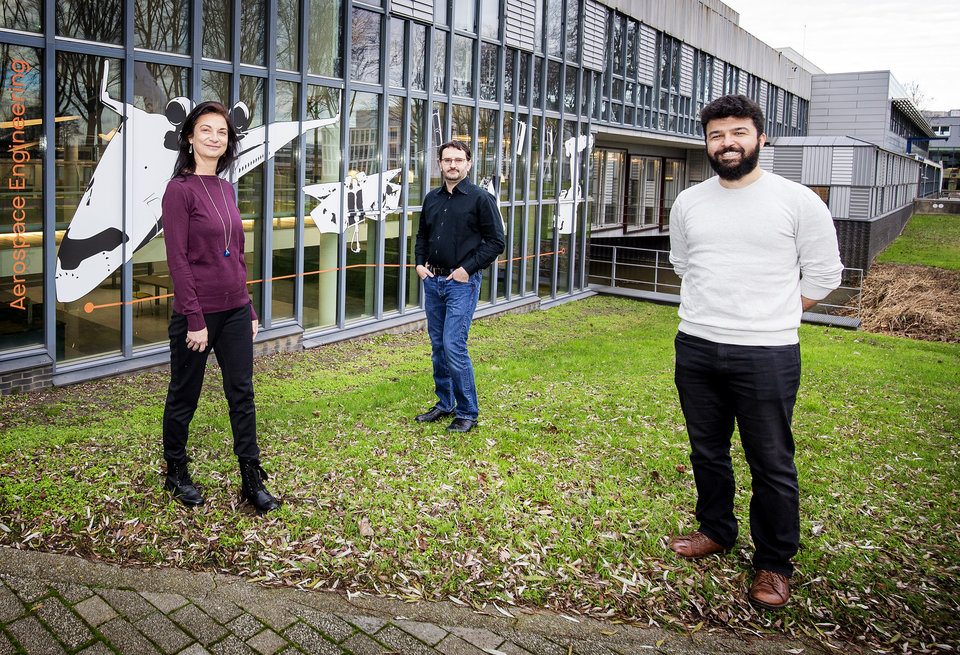

After finishing her PhD, Simona applied for and won the prestigious Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellowship, allowing her to settle at TU Delft. Since then, her research has expanded massively in scope. She noticed that there is no quantifiable way to indicate a structure’s heat wave resilience. After raising this concern with an EU commission, she was awarded 7.5 million euros to kickstart her proposed research project on multi-hazard analysis. Simona now heads a team of researchers working across Europe. Her position and experience gives her a unique perspective on design practices here in the Netherlands.

The wider world should understand that there are many dedicated researchers and companies working to make structures safer for everyone.

“Designers, even those from low-risk areas, should be aware of multi-hazard safety,” advises Simona. “The climate crisis unfortunately makes this topic increasingly relevant to our built environment. At the same time, I wish that the wider world would understand that there are many dedicated researchers and construction companies working to make current and future structures safer for everyone. Research and development unfortunately takes a lot of time, while disasters strike instantly. But be aware that every earthquake and fire is studied, and the lessons will be incorporated.”

This story is published in March 2024.

More information

Read more about Simona’s current research project, MULTICARE, on their website.

Header image and profile picture by Bas Czerwinski.