The Circularity in the Built Environment Graduation Award 2020-2021 produced no fewer than four prizewinners. New structures in the port of Rotterdam to strengthen nature in the city, a green corridor in Amsterdam with potential to provide energy and food, a digital tool to make it easier to recycle façade components and a public building that promotes social integration: these are just some of the graduation projects to emerge from the Master’s degree programme ushering in a circular future. Find out more about the winners in the four categories.

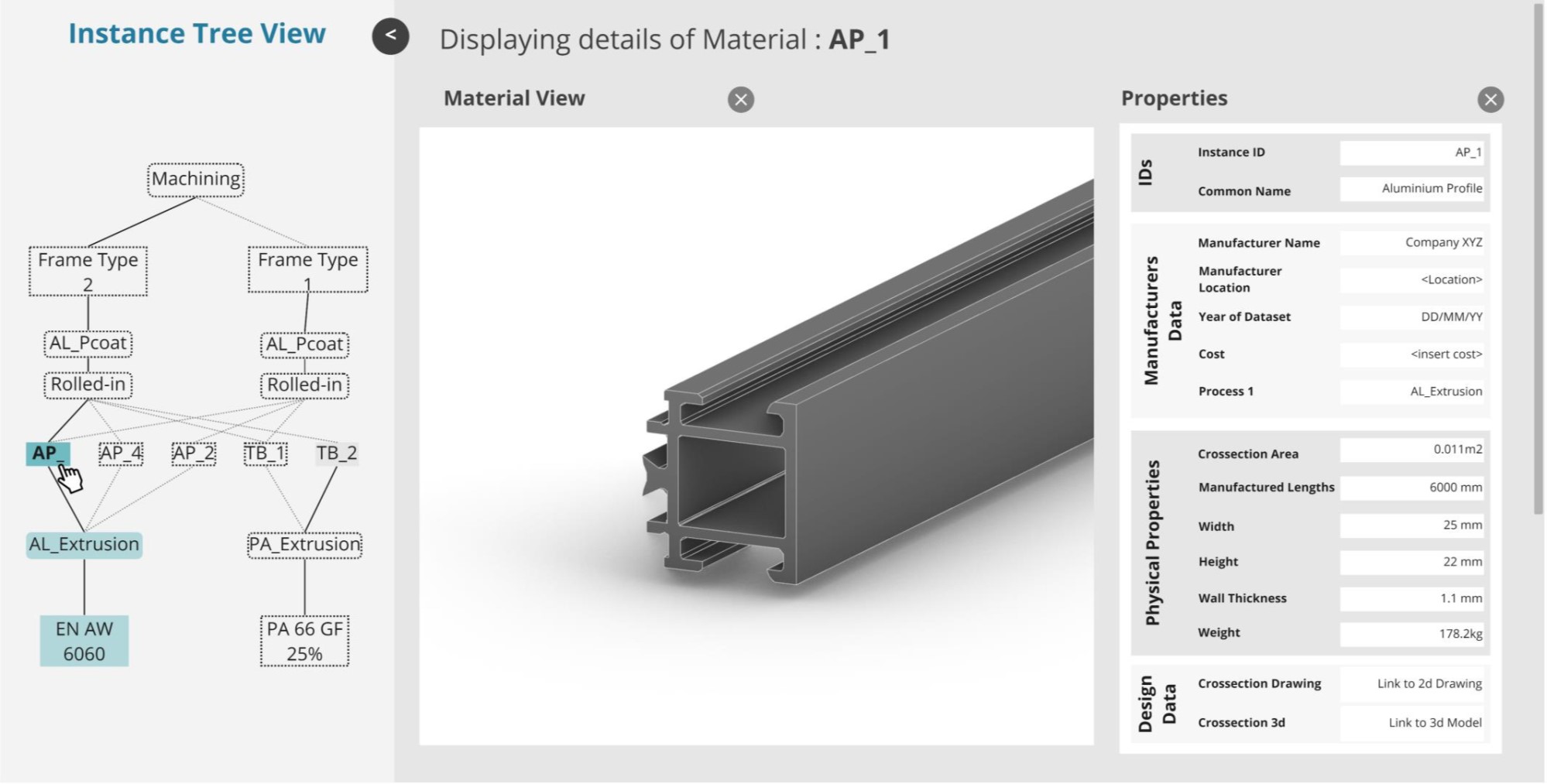

Façade Product Passport ‘under construction’

Abhishek Holla (Materials & Components) was working as an architect in India when he visited the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment in Delft in 2017 as part of a research project. He became interested in the curriculum and decided to take a Master’s degree. “In India, I was working on construction projects using prefab components. I brought this experience with me to Delft, where I studied façade technology in greater depth. The lectures were often on aspects of circularity, such as designing demountable façade components. I was intrigued by the question of how, once façade panels have reached the end of their lifespan, they can be at the beginning of a new product cycle.” He also got to grips with the world of computational design. “My graduation project brings both of these aspects together.”

Abhishek has great appreciation for the initiatives from the VMRG – Branch Association for the Metal Window and Façade Industry – to promote circular production of façades, to use emerging technologies for this, and to develop standards that lead to a high-quality re-use of façade components. “I was keen to further their work by developing a tool that can organise relevant information and use it to aid decision-making at the end of the lifespan of a building façade.” He started a preliminary framework using pre-existing knowledge in literature. “By asking people involved about the main difficulties and their desires concerning the information needed for re-using façade technology, I was able to develop the tool further and refine it.”

Façade components and materials usually end up on the scrap heap, in part because a lack of insight into the composition and residual value means it is not clear who will benefit from re-use of components or reclamation of materials. “Revenue models in the construction sector need to find more of a balance with the global footprint of building processes.” Abhishek hopes, for example, that making it clear how the carbon tax that applies to new materials relates to recycling can resolve this kink in the circularity process. “My proposal is to chop up the life cycle of façade components into phases that are associated with the registration of production processes, properties and performance. This gives a general reference framework for the actual CO2 emitted rather than an estimated average.” He is keen to stress that his research hasn’t produced any ready-to-use applications, but rather an industry wide framework which needs further refinement. “That will take a lot more time and energy, but we’ve made a start.”

Common haven for layered population

Prizewinner Luca Fontana (Buildings & Neighbourhoods) isn’t hanging about. He already worked for Studio Fuksas in Rome and next year he will be moving to London. During his studies in Delft, he was amazed at the apparent contradiction between the high degree of liveability in northern European cities, and Copenhagen in particular, as consistently shown in rankings, and the high degree of spatial segregation between ethnic groups. “Sometimes people simply can’t afford to live somewhere else, sometimes they feel happier in a neighbourhood with people similar to themselves. The fact is that for certain groups, such as people with a migration background, integration is difficult. I am a dreamer, but a realistic one. I don’t believe that you can do away with the causes of inequality using spatial design. But you can create an environment that promotes social inclusion.”

Luca came up with a redesign of the Skydebanehaven, a park with a playground in Copenhagen’s district of Vesterbro. He projected a public building in the park as a multifunctional and extremely accessible meeting place for people from diverse backgrounds. Haven, as his concept is called, is built up of vertical and horizontal platforms that allow a high density of usages and users. A room can function as a theatre or a library as required by the citizens involved, or as a room for yoga or judo classes.

This multifunctionality invites a diverse programme that by its nature appeals to a user group with a wide age range and background. The design is based on the circular business model called ‘Sharing Platform’ which consists of extending the use of a building by sharing it to many users over time. “MVRDV’s Ku.Be House of Culture and Movement in Frederiksberg served as an example. This is a large public building with a wide range of usage: from sport and play to art education. It is truly meant as a gathering place for city dwellers from all backgrounds.”

Haven links up with the city’s plans to make the location more accessible for residents from other districts, explains Luca. The idea is that a planned bike freeway will be part of a larger network for sustainable mobility that also increases social mobility in the city. “What I am actually doing is continuing the principle of increasing circulation of people in the city by using the building to encourage a higher degree of social traffic.” The platforms form large open areas, with hardly any walls or other partitions between users. “People can see and hear each other, they can move around freely and thus meet each other. The rooms are literally shared by many people, and so hopefully form a common haven.” Next to this the building largely consists of wood and is designed in such a way that the wooden skeleton can be used in facade renovations after the building’s end of service life.

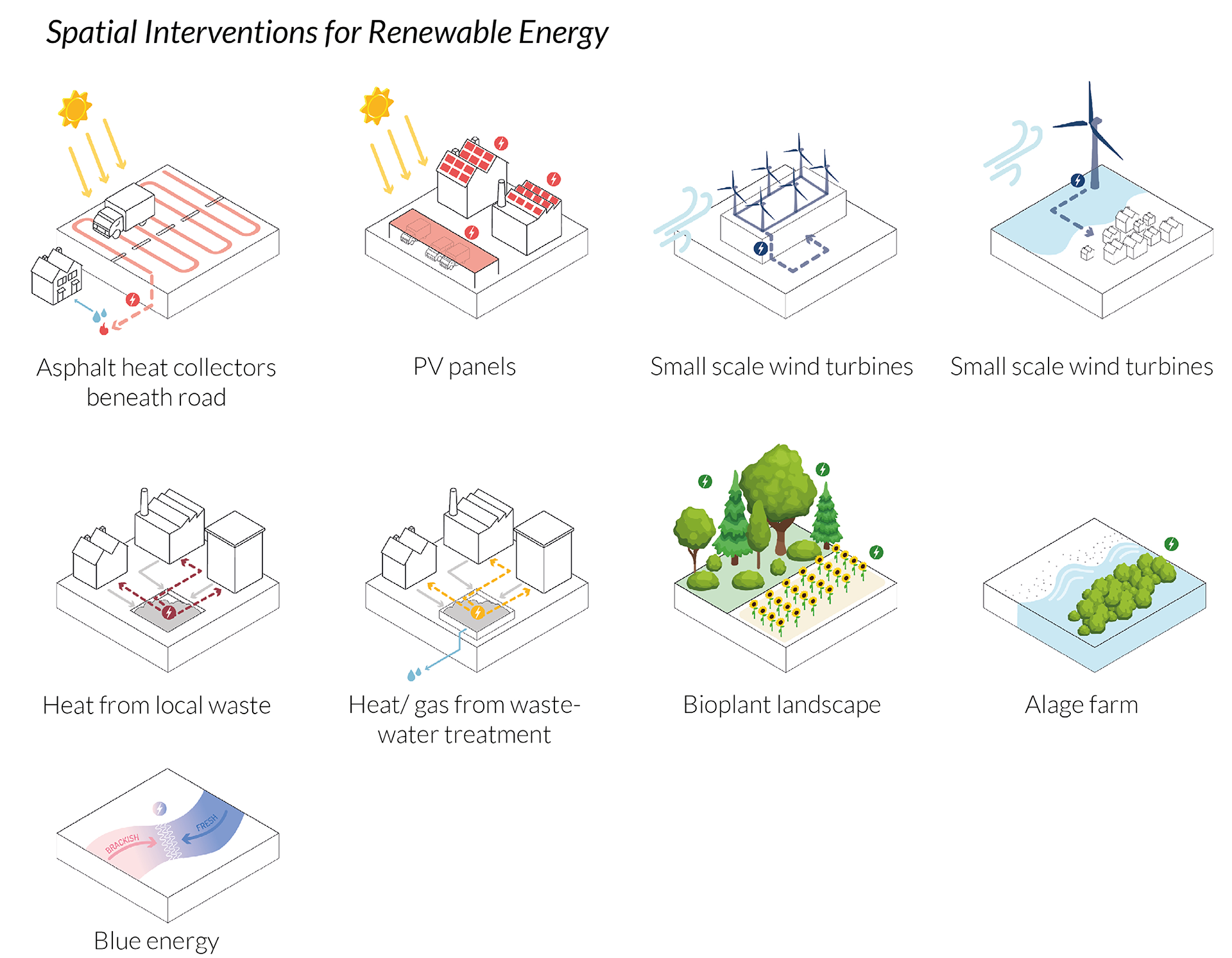

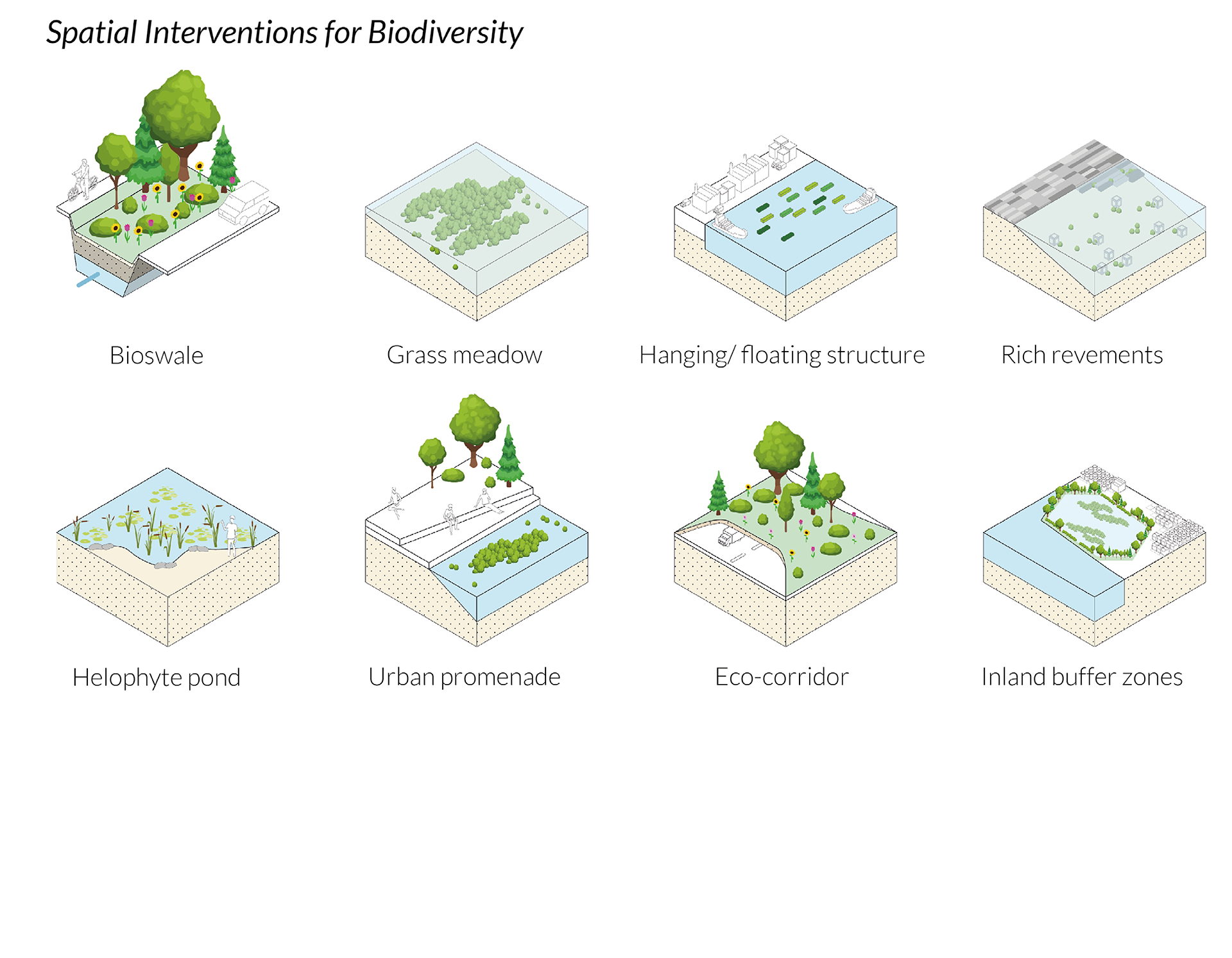

Heat generation and a wetland

From a social haven to the port of Rotterdam: shaped by industrial activity, the Waalhaven harbour district’s large paved surface area and unvaried vegetation mean there is a distinct lack of biodiversity. From the Urban Ecology and Ecocities design studio, Hanvit Lee (Cities & Regions) explored ecological values and opportunities to raise them.

She inventoried the existing flora and fauna in the harbour district as well as the opportunities for generating clean energy. She used this inventory as a basis for exploring the spatial interventions that would benefit the nature, environment and residents of the surrounding districts.

What infrastructures for renewable energy go together with the development of nature in the city? Hanvit came to the conclusion that generating heat and producing gas from wastewater and district heating from the processing of domestic and industrial waste are valuable and productive options. “But there are also many empty roofs where solar panels could be installed. And harvesting energy from asphalt surfaces could offer a solution here as well. You can create a good mix of methods to provide clean energy for the surrounding districts without burdening the ecosystem.” She also came up with various spatial interventions for creating more diverse or new habitats in order to enrich the area. “Examples include ponds with wetland vegetation that filter water and benefit insects and other animals, planted water buffers (bioswales) that filter rainwater and absorb it into the subsoil, and making harbour walls and other hard structures suitable for plants, shellfish and sponges to grow on. These in turn attract fish and birds. What’s more, floating vegetated structures can give wildlife a boost, both above and below water level.” Hanvit brought all these proposals together in a new spatial framework for Waalhaven.

The pièce de résistance is the construction of a wetland in the south-eastern corner of the harbour mouth. “This landscape is an important transition zone between land and water, with habitats that increase the biodiversity in the area.” Where the wetland adjoins the inhabited world with its busy roads etc., Hanvit envisages a bridge/ecoduct linking residents in the adjacent Charlois district and the wildlife in the substantial city park, the Zuiderpark, with the harbour district. “Corridors like this are vital for the spread and development of nature in the city.”

Self-sufficient food system

After taking her Bachelor’s degree in Turin, Eleonora Farcomeni (Cross-scale) did a Master’s programme in Delft in order to find out more about material and substance cycles in cities and districts. “As an architect, I want to be able to make buildings and areas based on circular design. You can see my graduation research as a proof of competence.” De Bretten, a green corridor with a surface of around 130 hectares to the south of Amsterdam’s western dock area, drew her attention. Could it be possible to create a communal food system that meets the needs of the local neighbourhood? Besides sports fields and allotments, the area also contains an area of wild landscape. “This nature area must be protected. I have endeavoured to tap into the local resources using a minimum of interventions.”

Eleonora was inspired by the Parc de la Vilette in Paris, where a range of different landscapes and functions have been created using modest interventions. “At the heart of my design is a pavilion, The Food Community House, which plays a central role in a food system which combines gardens and fields used for organic food production with social activities such as harvesting and communal preparation of food. The idea is that this place encourages local residents to a more conscious use of food.” The pavilion has a modular design with components made of locally sourced timber, such as willow.

Reeds are used as an insulation material. “I found out that alder, which also grows in De Bretten, makes an excellent foundation material for the moist ground here. Did you know that Amsterdam and Venice are partially built on alder piles?” The energy needed for the building is available in the form of biogas obtained from composted green waste. Rainwater is collected for use as grey water or for watering plants. Eleonora made grateful use of a calculating tool developed by a PhD researcher for estimating the space required for producing a certain amount of food. “This enabled me to calculate how, using a sophisticated variety of crops, we can use around 13% of the 120 hectares all year round to produce 2,000 weekly food parcels for the surrounding neighbourhoods.” So there is still scope to scale up operations.

In the last two years, there has been no time to sit around. In her spare time, Eleonora helped to design the energy-neutral house which the SUM student team from TU Delft is hoping will give them a top position in the Solar Decathlon Europe. From November, the prototype can be seen in The Green Village, a field lab on the TU Delft campus. “The event is taking place in June 2022 in Wuppertal, so it’s an exciting wait.”

More information

The complete theses are available through this link.

Circular design and construction in the curriculum

“In Delft we are increasingly successful in interweaving circularity in our education programme,” says Olga Ioannou, Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment and one of the driving forces behind the Circular Built Environment Hub. “The Hub arose from the knowledge and enthusiasm of many employees who are committed to making the built environment more sustainable. Circularity now features as one of the six central themes that will drive our future education. By organically adding new learning materials and activities, we are developing ubiquitous learning pathways for this theme both in bachelor's and master's education. Circularity is thus becoming increasingly embedded in our curriculum, but also in our consciousness. The students we welcome here, regard circularity to be a very relevant issue of our times and expect to learn so much about it that they can then contribute to it as experts. I think this second edition of the Circularity in the Built Environment Graduation Award bears witness to that. Furthermore, with our growing series of online courses on circularity and a first Summer School on Circularity in the Built Environment, we also hope to reach and involve as many interested parties outside our program as possible.”

Abhishek Holla

Category: Materials & Components

Luca Fontana

Category: Buildings & Neighbourhoods

Hanvit Lee

Category: Cities & Regions

Eleonora Farcomeni

Category: Cross-scale

Graduation Award 2021-2022

Students from the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment TU Delft who graduate this academic year on a topic related to circularity can participate in the third edition of the Circularity in the Built Environment Graduation Award.