Artificial breeze reduces heat in cities

More vegetation in cities lowers the temperature but how do you plant more trees, plants and bushes in city squares without compromising the function of these public spaces? In the case of The Green Village, drones, data and artificial breezes ensure an optimum design. “Creating green areas to reduce temperatures sounds simple but it is actually a lot more difficult than one might think.”

By Karin Postelmans • April 6, 2023

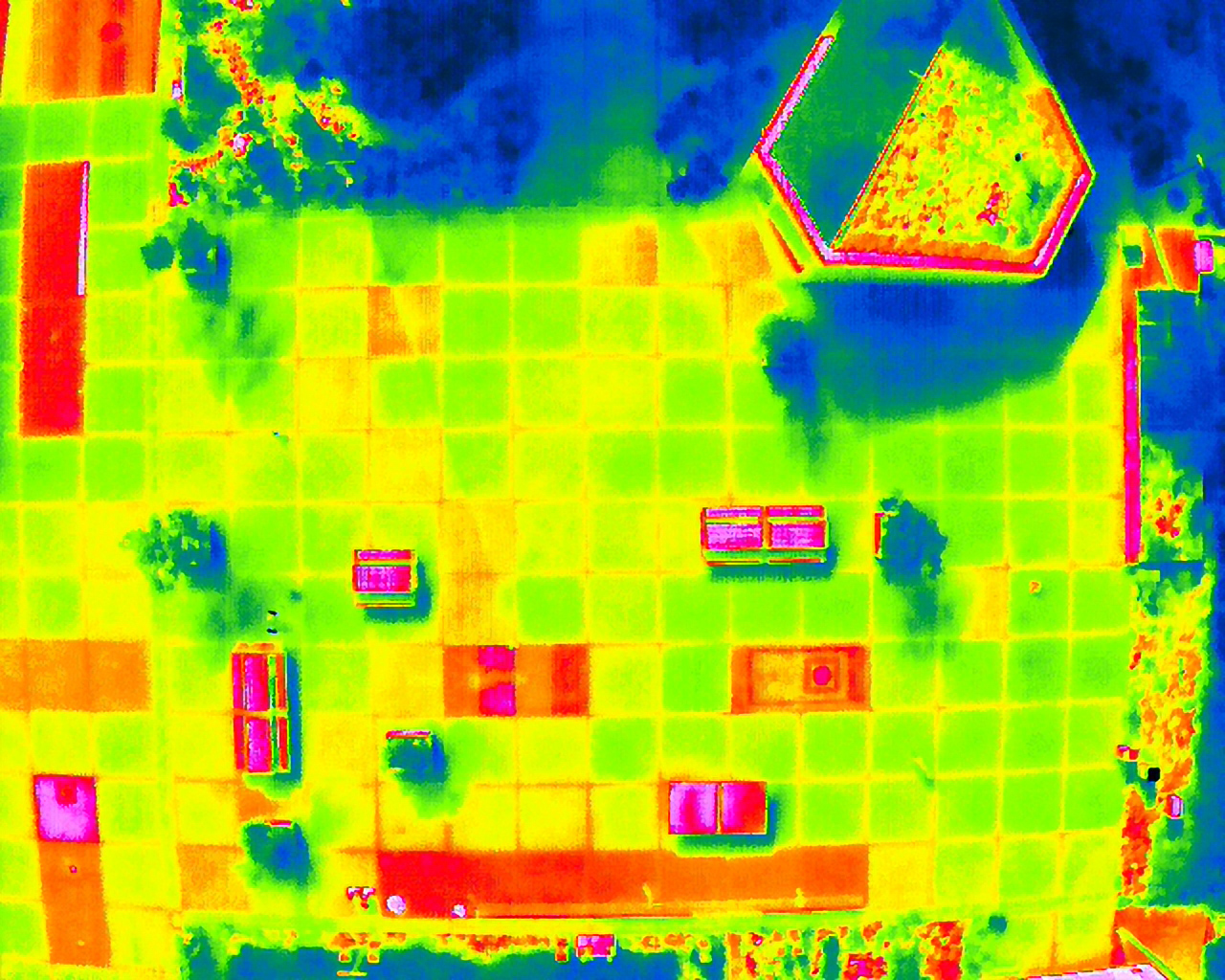

The HittePlein (Heat Square) has been sandwiched between several buildings at The Green Village for a couple of years now. It is a perfectly ordinary square, the type you might find in any village or town, but this is where solutions for heat stress are developed. So far, these innovations have been tested separately from one another. What is their combined effect? And how do you make sure that the square also retains its functions? After all, it has to remain accessible to suppliers’ lorries, for example.

“We are collaborating with researchers, entrepreneurs and the authorities to find answers to these questions”, says project manager Willy Spanjer. “This autumn, we are transforming the HittePlein into the ‘KoeltePlein (Coolness Square)’. An integrated design, which serves both people and climate, has been drawn up for this transformation. We are going to learn a lot from it.”

Fieldlab ID

| Fieldlab | The Green Village |

| What happens there? | Field lab for sustainable innovation in the urban environment |

| Project | From HittePlein to KoeltePlein |

| Objective | To use vegetation to reduce heat stress in the city |

| Size/value | 550 m2 |

| Researcher | Eva Stache, doctoral candidate and architect |

| Partners | BAM Infra Nederland and the Province of Zuid-Holland |

| Buzzword | Ecosystem services |

Climate neutral

Among other things, the plans for the square/field experiment involve various species of plants and will test different types of paving and innovations for the storage and management of rainwater. The design will also contribute to research into the effect of vegetation on the urban climate being carried out by architect and doctoral candidate Eva Stache.

Stache: “Our ambition is to produce a water, energy and climate-neutral setup. We can only do that by making the best possible use of plant species which are useful for climate adaptation. You must, for example, know how much water they transpire and whether you can walk on them.” As yet, there is no databank with this kind of information, so Stache worked it all out for herself. And she divided strips of vegetation into sections to test different types of plants.

Artificial breeze

The fact that plants cool the air around them by transpiring moisture has a key role in the design. They need water to be able to cool their surroundings, but this is becoming more and more of a problem during our hot and dry summers. Rainwater storage has therefore also been included in the design. Furthermore, the cooled air must be dispersed. To this end, Stache has used an ingenious method to create an artificial breeze.

This breeze is generated by two strips of paving between the greenery. The paving is black in colour and therefore becomes much warmer than the vegetation. The strips vary in width, running from narrow to broad, resulting in air movement and the creation of a breeze. The breeze is not only a way of expelling hot air from the city, it is also, and particularly, intended to raise the wind chill effect.

In her research, Stache takes those using the square, such as pedestrians and suppliers, into account too. “Creating green areas to reduce temperatures sounds simple”, says Stache, “but it is actually a lot more difficult than one might think.”

The Heat Square at The Green Village, sandwiched between several buildings

Additional challenge

An additional challenge in designing for climate adaptation lies in the requisite overall view of the spaces in the city: the surfaces, the water and the walls. Stache: “Each of these elements has a different owner. If the reflection of sunlight on your building causes my square to heat up, who is going to pay for trees to provide shade? This is why you have to do everything together. BAM and the province understand this. They already know that even if they do not make an immediate profit, the investment will be very beneficial in the long term.”

The unique thing about The Green Village is how fast innovations are developed. According to Spanjer, the realistic setting and TU Delft’s multidisciplinary team contribute to this. “And collaboration with partners, such as municipalities, who will be the ones to roll out the innovations. Their feedback is indispensable when scaling up.”

Construction company BAM Infra, for example, translated Staches’ design into a design that can be implemented. Bas de Jong, BAM project leader: “The balance between climate measures and retaining function is often difficult; that applies here too. Our experience enabled us to make the design realisable and safeguard the objectives. And we are gaining inspiration for heat-resistant urban planning at the same time. There is demand for it.”

Demonstrations

“I recognise that,” says Astrid de Wit, the Province of Zuid-Holland’s programme manager for climate adaptation. “Municipalities and companies are responsible for adapting to climate change but they are still searching for solutions. That is why we are supporting The Green Village. And connecting governmental and non-governmental parties so that they can exchange knowledge.” De Wit takes municipal representatives to demonstrations at the HittePlein on a regular basis. Afterwards, people frequently say: “We were not aware that so much is possible”. The exchange of ideas also yields insight into the challenges. For example, a discussion with the building sector revealed that legislation is hindering progress. “So we are talking to the Ministry of the Interior about that.”

Experiments at the Heat Square

More vegetation in cities lowers the temperature, but what ensures an optimum design?

Drones

Last summer, a student applied various techniques, including the use of heat images from drones, to monitor the Hitteplein for his final project. He measured everything: temperature, air humidity and precipitation. Spanjer: “This gives insight into the effect of the measures taken, which we can use to develop new design principles.” But we have not reached that stage yet. New researchers are waiting in the wings to measure the effects of the transformation from Hitteplein to Koelteplein next summer.

Usable innovations

De Wit wants to come and have another look after the changes have been made. “You know that usable innovations are going to emerge because so many parties are collaborating. That is the best thing about TU Delft. New products or concepts transcend the status of ‘innovation’ and become standard applications almost before they are even finalised.”

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/_processed_/8/3/csm_NoordzeeWind%20wind%20farm%2C%20Netherlands_169_resized_5bc0ad6e0e.jpg)