Unburdening the power grid with energy hubs: here’s how it works

Technically, it can be done, but in practice, it rarely succeeds: better matching the supply and demand of energy users to generate and use more power with the same grid. For her graduation project, TU Delft Odile Niers designed four interventions that succeed in initiating energy hubs in business parks. "We need to focus a lot more on social relationships," she says.

Sometimes I read alarming reports about grid congestion, but I haven’t notice anything yet.

“In a year's time, everyone will have to deal with it. In many places, companies are already noticing that they cannot grow or become more sustainable. For instance, they are not allowed to fill a large roof with solar panels or install new, heavy machines in their factory, because the power grid cannot handle it. In theory, heavier power cables could solve this issue, but there are too few people and too few materials to make this happen fast enough. We really need a different solution.”

Have you been working on such a solution?

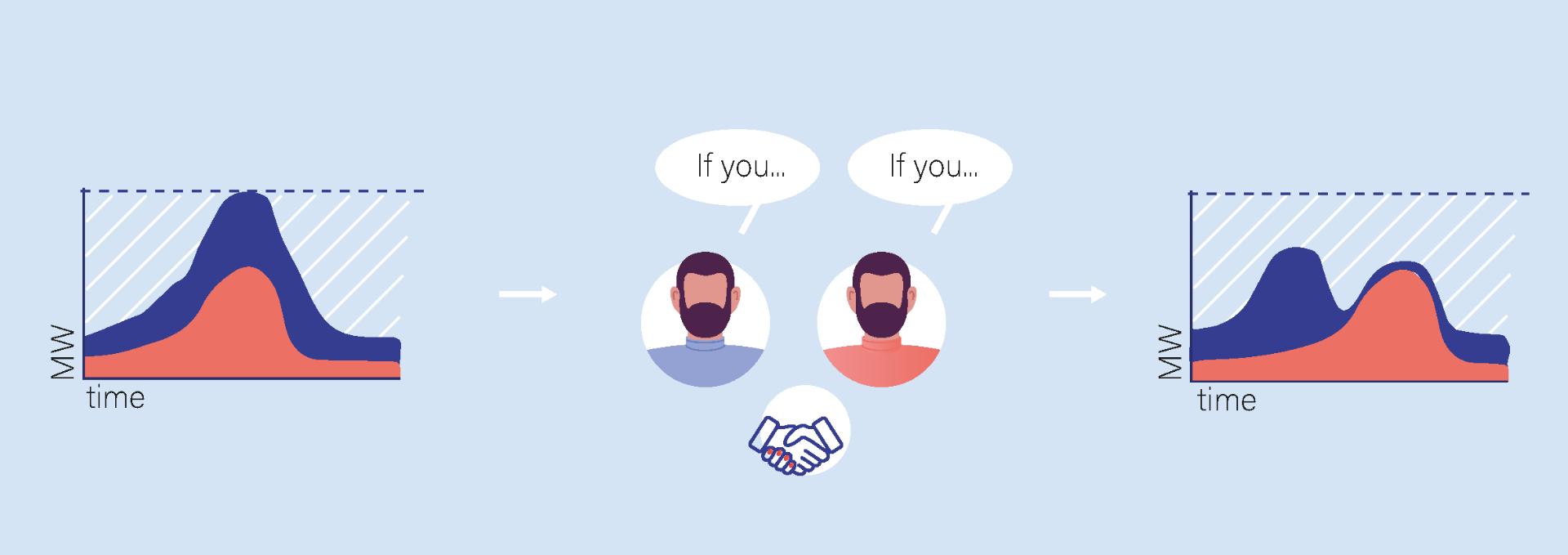

“With the grid operator Stedin Group, I have been working on one of the ways you can solve grid congestion: the energy hub (or e-hub for short). An e-hub is a smart energy system that integrates and optimises the generation, storage, and distribution of energy at a local level. An e-hub can be a closed energy system, but the growing trend is towards e-hubs with virtual grids.

In this type of situation, a group of energy consumers and providers agree on when to supply or draw power. For example, two factories with high power demands may agree not to operate their heaviest machinery at the same time. One factory would delay turning on its most energy-intensive machines, allowing the other to operate at full capacity. The benefit is that both can expand operations or become more sustainable. They can save money by generating their own power or doing less with gas and more with electricity.”

Why is it so difficult to establish this kind of energy hub?

“The technology is there, but before you can install it, all of the companies within the e-hub must first form a group and reach agreements together. However, entrepreneurs often know very little about their energy consumption or the opportunities it offers. They have also never had to cooperate with their neighbours like this before, and different interests can cause a lot of delays. Supporting parties like grid operators, municipalities, and provinces are working hard to offer more clarity and support to business parks. As for the everyone else, they are still searching for the best way to achieve this.”

What have you discovered so far?

“Every business park is different, and it is nearly impossible to develop a standardised approach. An interesting thing I found was that e-hubs are easier to establish in smaller or faith-based communities. For example, I visited a business park near the small town of Tholen in Zeeland and in Veenendaal in Utrecht. The entrepreneurs there know each other well, either through living in the village or through church. They tend to want to look after one another. Their thought process is: if my neighbour benefits, I’ll take part. In larger cities, it becomes more difficult. Even though the companies themselves benefit from the e-hub, you’re more likely to hear: ‘I don't know my neighbour, so why should I?’ This results in more differences between the business parks and entrepreneurs.”

How do you get around an impasse like this?

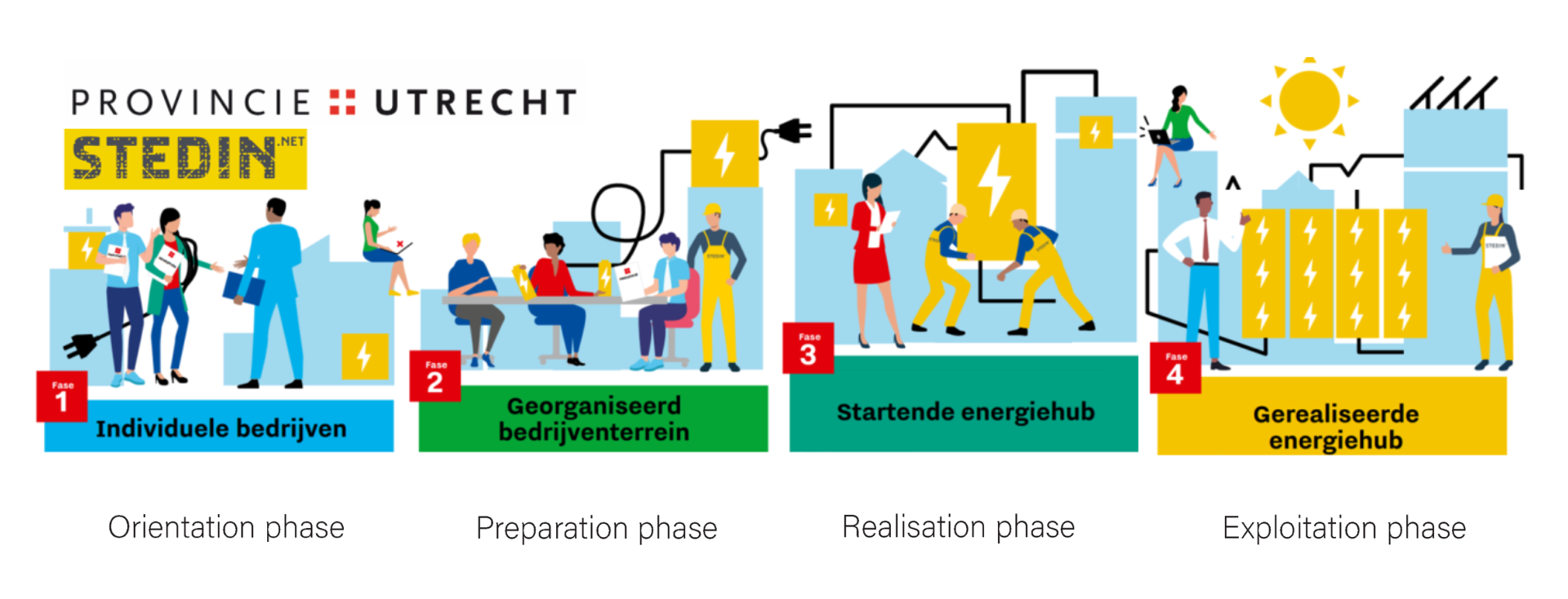

“I mapped how this complex problem fits together. Then, together with energy transition experts, I used data from interviews and visits to events and business parks to design four interventions that provide a springboard for entrepreneurs, network operators, and municipalities. These interventions ensure that the exploratory phase of the e-hub goes more smoothly. Within this process, entrepreneurs enter into collaborations and explore initial opportunities.”

What exactly do the four interventions you developed entail?

“The first intervention focuses on developing a clear, comprehensive, and interactive knowledge base that grows with the innovations. The second intervention helps select companies that are interesting in forming an e-hub together. The third intervention is a series of workshops, during which companies meet, discuss interests, and form a group. Then they get to work on exploring technical and financial options. The last one focuses on bringing supporting parties (e.g. grid operators, municipalities, provinces, and consultants) together to share lessons from different e-hubs and to accelerate innovation.”

What have you learned along the way?

“That we need to focus a lot more on social relationships. There is no point in a workshop that mainly talks about technical possibilities and business models. During these workshops, entrepreneurs need to develop a sense of team spirit. One person may think that an e-hub is important because it can save them money, while another thinks sustainability is important, and yet another wants to be able to grow. The common denominator is that they can get it done together and everyone benefits.”

“I think this approach can be an eye opener for other issues where an area-based, cooperative approach is needed. For example the nitrogen crisis, water management, or the construction of housing. Even with these problems, it is important to realise that there is no universal solution or guide. Governments must provide the right resources to encourage bottom-up solutions.”

How did you manage to achieve what wasn’t possible before?

“The problem of grid congestion is so acute now: it hits entrepreneurs in their pockets. This makes them want to take action now, whereas before, it wasn’t as much of a priority for them. I was warned by the students who researched energy hubs before me that I would need to send out many interview requests, as not many people wanted to be interviewed. So I did, but then almost everyone wanted to cooperate, because they were all interested in energy hubs! This provided me with a lot of work, but also a lot of knowledge. I conducted as many as 34 interviews with entrepreneurs and supporting parties (e.g. people from provinces, municipalities and managers of business parks).”

Do you think you were especially lucky because you started at the right time?

“I think my educational background came in handy for this. During my bachelor’s degree in Industrial Design Engineering at TU Delft, I learned how to solve problems in a way that the solution actually works in practice. I was taught how to focus on a solution that is feasible, viable, and desirable. Therefore, I automatically paid close attention to what people actually wanted, as well as, what their motivations and barriers were.

During my Master’s in Industrial Ecology at TU Delft and Leiden University, I learned systems thinking. This allowed me to properly map the complex problem of grid congestion and entrepreneurs, and then identify hotspots for improvement. This combination of studies gave me a lot: solving the right problem and solving the problem right.”

What was the best moment of your graduation project?

“It was at a knowledge-sharing event hosted by the Province of Utrecht. There were about 100 people, including people from companies, government officials, grid operators, and technicians. The event took place at the end of my graduation project. I presented my results on posters. The question was: how could these people realise and implement the four interventions? I led a number of sessions where participants could stick sticky notes with suggestions to a poster. It yielded a lot of interesting results. The Province of Utrecht has now started working with the input from these sessions, which is very cool.”

What are you going to do now that you have graduated?

“I am very excited about the energy transition, because it connects a lot of issues. Every problem has a technical, financial, and social side. I think it would be cool to continue implementing systems thinking in order to use it to accelerate the energy transition. But first, I'm going on a holiday!”