Co-creation

A brief history and definition of co-creation

The term co-creation was first coined in the year 2000, in a Harvard Business Review article titled Co-opting Customer Competence, written by professors from University of Michigan. Initially focused on co-creation between customers and enterprises.

Co-creation as a concept has been evolving and emergent over the years and has taken many forms in different disciplines and domains. In the 1960s, Trade unions in Scandinavia extended the Workplace Democracy Movement to the right of workers to co-design the IT systems that impacted their work. They called this cooperative design, which later translated to participatory design during the 70s in the US. In 1971, the concept of collaborative inquiry was coined as a form of participatory research method in the social sciences, focusing on researching ‘with’, rather than ‘on’ people. During the 80s urban planners adopted the concept in the form of collaborative place making or collaborative planning. A 2010 book titled Power of Co-creation expanded the term beyond customer-enterprise value creation, to include stakeholders within any organisation.

A defining principle of co-creation, also ratified as an international standard for human-centered design is the “involvement of users throughout design and development.” Today, co-creation has become a mainstream term that encompasses prior concepts such as participatory design. And is now being applied by organizations, to collaboratively design strategy, process, and culture. “Co-creation is a term that traverses a philosophy, method, and mindset of collective creativity (Coddington et al., 2016)”

Why is co-creation relevant?

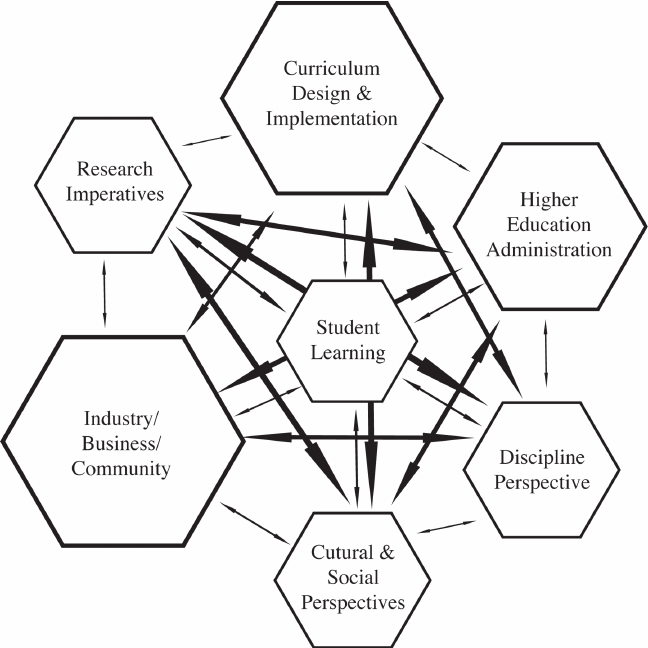

Education considered as a complex system, is composed of multiple interconnecting components. These include independent actors, organizations, material infrastructures and natural environments, entwined in layers of meaning, discourse, social values and desires, rules, political views, histories and more (Van Der Bijl-Brouwer et al., 2021). Therefore, innovation in education often aims to address complex and everchanging challenges that affect and impact the many components and stakeholders involved.

Co-creation as a participatory and collaborative practice can address the evolutionary nature of complex challenges, by enabling engagement with expertise from across disciplinary fields and organizational silos. More specifically, co-creation offers an inclusive and sustainable approach for social innovation within a complex context such as that of education. Literature, desk research and experiences all point to many values of co-creation within the innovation process. Some of these are listed below:

- Increases in individual competence

- Support for the outcome

- Perceived legitimacy of process

- Strengthened social networks

- Inclusion and sense of belonging

- Ownership, empowerment, and agency

- Information exchange and transparency

- Skill sharing

- Sustainability - adaptive systems that allow for iteration

- Deepen academic engagement

- Encourage persistence

- Validating ideas - ensuring the generated solutions are valid for the users it impacts

- Stimulating autonomy – as stakeholders (students) take responsibility

Co-creation in practice

A co-creative approach can be employed in a variety of ways using different methods depending on the context and needs of the project. The value of co-creation lies in the methodologies that enable participation and allow inclusion, for sustainable innovation. Methods of co-creation may range from providing appropriate information to stakeholders to make informed decisions to citizens coming together for the purpose of improving their neighbourhoods with the involvement of government bodies.

As part of a co-creative approach, it is equally important to determine and assess to what extent stakeholders are being involved. Harder, Burford and Hoover (2013) describe this as, the levels of participation (list below). They specified the levels specifically for cross-disciplinary use, and these levels resemble what Sanders (2006) describes as the roles that people have played over the years in the design engineering process.

Examples of co-creation from different domains and varying contexts have been compiled to give a glimpse of how co-creation can be used in practice and add value to the process of innovation.

Paradoxes and drawbacks

Co-creation has gained considerable traction in the recent years owing to its value as a sustainable approach for social innovation in a complex context. Yet the still evolving approach is not without challenges and paradoxes, given the participation and inclusion of distinct stakeholders all with their own unique backgrounds, perspectives, and so on. The approach may result in further conflict and require sophisticated conflict resolution, and furthermore lead to co-destruction of existing norms and structures. Steen et. al. (2018, pp.284-293) highlight the dark side of co-creation and co-production in the context of public services and citizen engagement. This includes:

- Deliberate rejection of responsibility

- Failing accountability

- Rising transaction costs

- loss of democracy

- reinforced inequalities

- implicit demands

- co-destruction

Other challenges towards co-creation, in an educational context based on inputs from the study climate team include:

- Co-creation being an evolutionary process, is carried forward by various groups, and thus dependent on participation and engagement of different and at times disparate groups. For instance, students spend only a few years at a university, lecturers who may be new, or those who have been at the university for years.

- A high level of participation requires appropriate distribution of responsibilities and ensuring accountability amongst stakeholders. This is especially challenging, given the diversity of stakeholders from novice versus experts' status, social identities, gender parity, historical representations.

- Existing structures have a place in current systems and many times provide stability. Co-creation may question, challenge, and disrupt such systems. Furthermore, reversible, and prototypical solutions that emerge from co-creation may be seen as temporary, generating lack of trust and its adoption difficult.

It is important for researchers and innovation practitioners to address the shortcomings and continually reflect on the approach, to maintain credibility within the co-creation process.

Co-creative approach at Study Climate

As part of the Study Climate team and practitioners of social innovation within education, co-creation can enable us to pursue inclusive and sustainable projects relevant for the many stakeholders involved. Including students, educators, support staff and management personnel. A few emerging questions that we would like to further explore are:

- What is the current understanding of co-creation at TU Delft?

- What are the existing co-creative initiatives at TU Delft?

- How can we develop the tools to enable a co-creative practice?

- How can we integrate a co-creative approach in rigid and at times hierarchical structures?