'Elderly' first Dutch nanosatellite celebrates fifteenth birthday

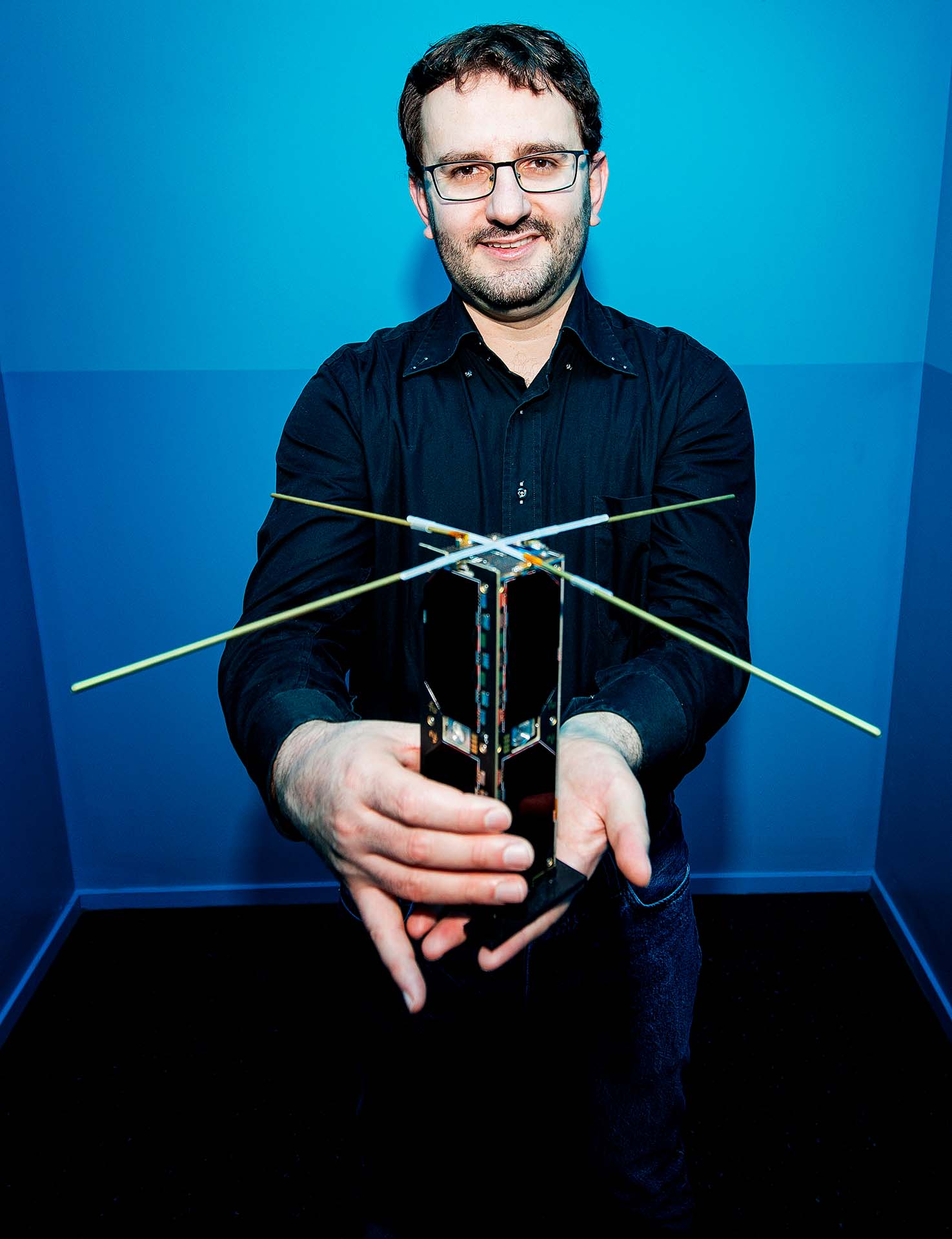

She is affectionately referred to as "the old lady". After 15 years in space, she can safely be called very elderly. Few of her peers are still operational at her age. But the old lady is also hard of hearing and barely understandable. This month, the self-proclaimed adventurers who built her, celebrate her birthday but fear it will be her last. Proud father of the very first hour Chris Verhoeven (Faculty of EEMCS) and current caretaker Stefano Speretta (Faculty of AE) describe the Delft nanosatellite Delfi-C3 that exceeded all expectations.

Adventurers

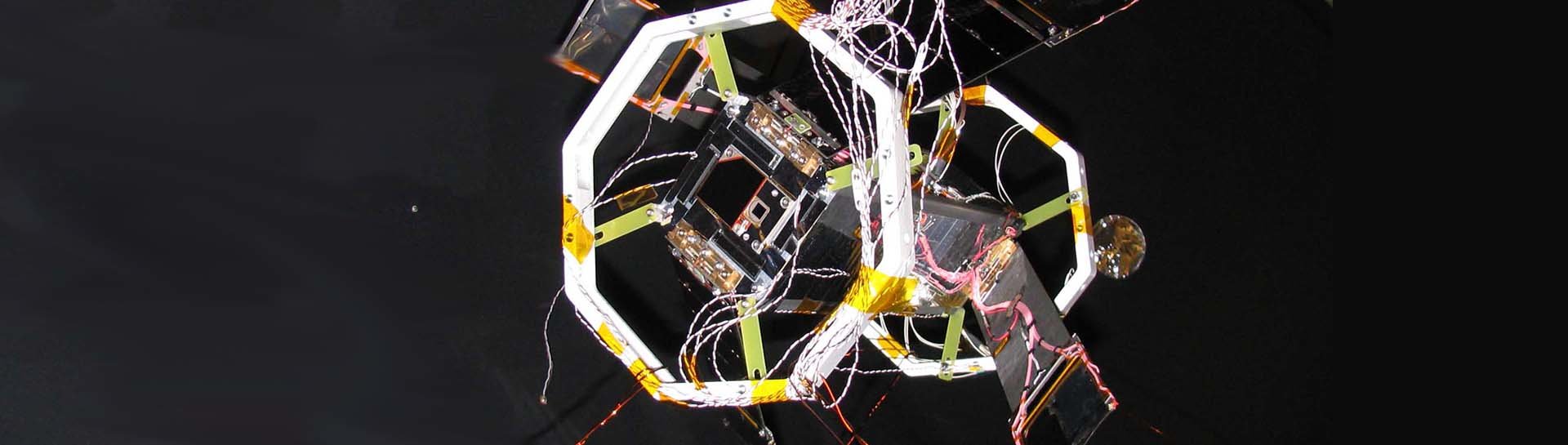

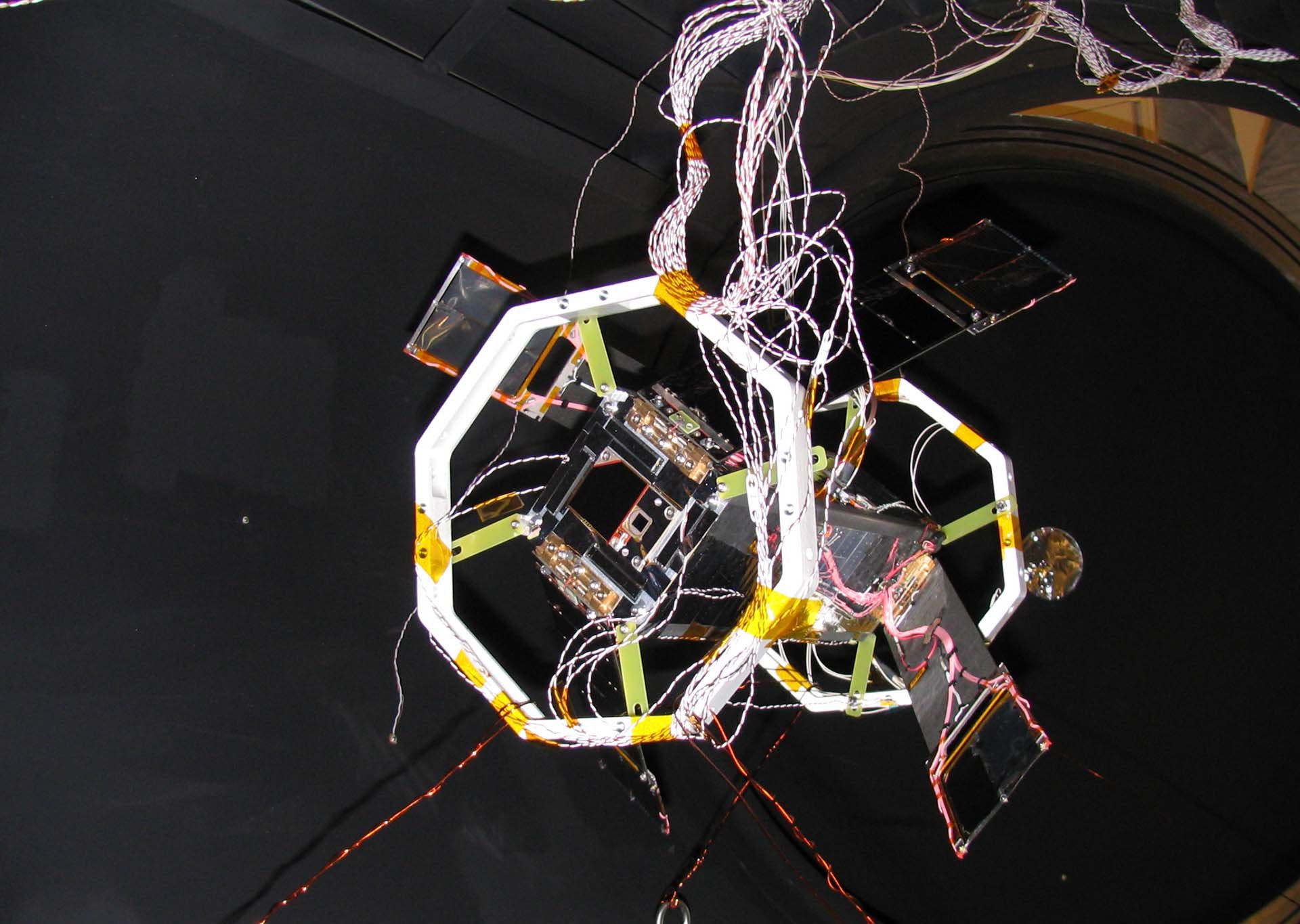

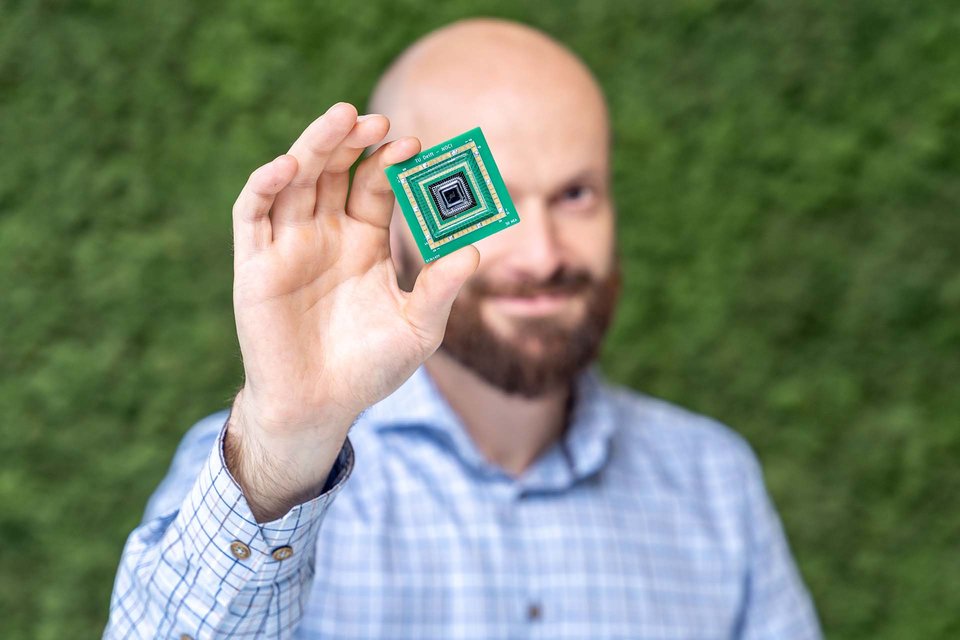

Who, or what, is Delfi-C3 anyway? Chris: “She came about thanks to a bunch of fascinated adventurers. And a large team of 60 students who were mesmerised by the challenge.” Stefano: “Students can easily read in a book what a satellite is, but it is much more impressive if they can build one themselves that will actually go into space.” When the students and supervisors came up with the plan to build their own satellite, everyone thought they were crazy: satellites were big and took 20 years of preparations. A nanosatellite was labelled in advance as space junk. “We didn't know it was impossible, so we just did it,” says Chris. Spurred on by department leader Wim Jongkind, the adventurers built a tiny satellite weighing just over 2 kg, full of consumer electronics. The design followed the 'keep it simple, stupid' principle. On board a few panels of (then innovative) thin-film solar cells and a small experiment with radio communication.

Life-changing event

When the satellite went into space, Chris and his team kept the cork on the champagne. It only went off when the ground station, on top of the roof of the EEMCS building, made contact with the satellite for the first time. The champagne spilled over a laptop, which immediately died. “And what happens then,” says Chris, “might be similar to the birth of your first child. The satellite sound that you know so well, you now suddenly hear coming from space with noise and Doppler effect. She's up there and responding. It was a life-changing event for us.”

Relentless

Once in space, the battle between technology and elements began. The radiation is unrelenting, especially when the sun becomes extra active. As a result, the electronics slowly degrade. Stefano: “We monitor this process closely. The data may help others predict how the decay will progress at the first signs of degradation.” But Delfi-C3's greatest achievement is that it did what it was made for, and still does so today. “We have proven that it is possible to build a working satellite all by yourself.”

Achievements of note

Delfi-C3 will not necessarily be remembered for scientific breakthroughs. She herself is the breakthrough, Chris says passionately. “With a scientific article you can't fly to space or stop the sea. No, pioneering with technology, that's what the T in TU stands for. When engineers from all kinds of faculties at TU Delft work together, things get done. The first Dutch nanosatellite. The first professional nanosatellite. And along the way, we discovered that with a simple 80-cent temperature sensor, you can measure Earth's orbital parameters within a few percent accuracy. Thanks to Delfi-C3, we already had the ideas in 2003 that Elon Musk is now realising with Starlink. Those are all achievements of note.”

Last words

The old lady has had a great impact on her family. The students of that time founded ISISSPACE, now one of the largest space companies in the Netherlands. “All thanks to Delfi-C3,” emphasises Chris. The team meets annually and discusses how their satellite is doing. Stefano: “We fear that she won't last much longer. Delfi-C3 is in a slowly declining orbit, and eventually will burn up completely.” The people who heard her first words are ready to catch her last ones as well. “That is quite a puzzle, as it is becoming increasingly difficult to communicate with Delfi-C3. Also, the software we used 15 years ago is no longer supported.” Chris is not ready yet: “Delfi-C3 has changed a lot of lives. I can't bear the thought of it being over any time soon. I'd like to have the satellite back. Or at least take one last picture before she is gone for good.”

Can-do mentality

The can-do mentality surrounding Delfi-C3 is still very much alive. Two other nanosatellites have already been launched, and a third is in the pipeline. Stefano: “Students continue to develop new components. That’s how we educate a new generation.” With Delfi-C3 having paved the way, next steps can be taken with its successors, for example towards the collaboration of a whole swarm of miniature satellites for mapping climate change. “My dream is to measure the density of the atmosphere in the area between 100 and 300 kilometres altitude. Little is known about that at the moment,” says Stefano. Meanwhile, Chris dreams of building a lunar lander together with students. One that is just as robust as Delfi-C3. “We want a sign of life coming from the moon.”

Ultimate survivor

For the time being, Delfi-C3 is still being heard every day. “It may not be healthy, but I get an email every day when our ground station has made contact with the satellite,” says Chris. “She is the ultimate survivor.” And he is quite sure: if in 500 years a book is written about TU Delft, Delfi-C3 will feature prominently in it.