In early May, Olivier de Gruijter packed a large box of Jerry Can Water Filters. Each one is handcrafted in his workshop. Finally they are going out into the real world, something he has been looking forward to for a long time. Refugees in Gaza and Iraq are going to use the prototypes for the first time. After studying Industrial Design Engineering, De Gruijter came up with a smart, compact water filter that you can screw onto any standard jerry can. A unique and sustainable filter system that rinses itself clean.

In the workshop of product designer Olivier de Gruijter there are about 150 black-grey tubes waiting in line for their matte, deep-blue casing. ‘Jerry', is written on the side of the casing. De Gruijter twists a brush of glue around the end of the tube and attaches the appropriate coupling piece. Everywhere you look there are washers, jars of glue and filters. He hands the tube to one of the students across the workbench. With great care, she assembles the filters. The end station is a large cardboard box with destination Palestine.

A pumping noise can be heard in the background. In the corner of the workshop is a device that tests the Jerry water filter continuously, a kind of Ikea chair test. Currently the automatic arm is making thousands of perfect pumping motions, but soon it will be the hands of the first users in refugee camps in Gaza and Iraq. De Gruijter is curious to see if it works as well in practice as conceived on the design table. "What if a child uses it as a water plaything? And will they use the filter even if you need ten liters of water? We're at a point now where we can still tweak the prototype."

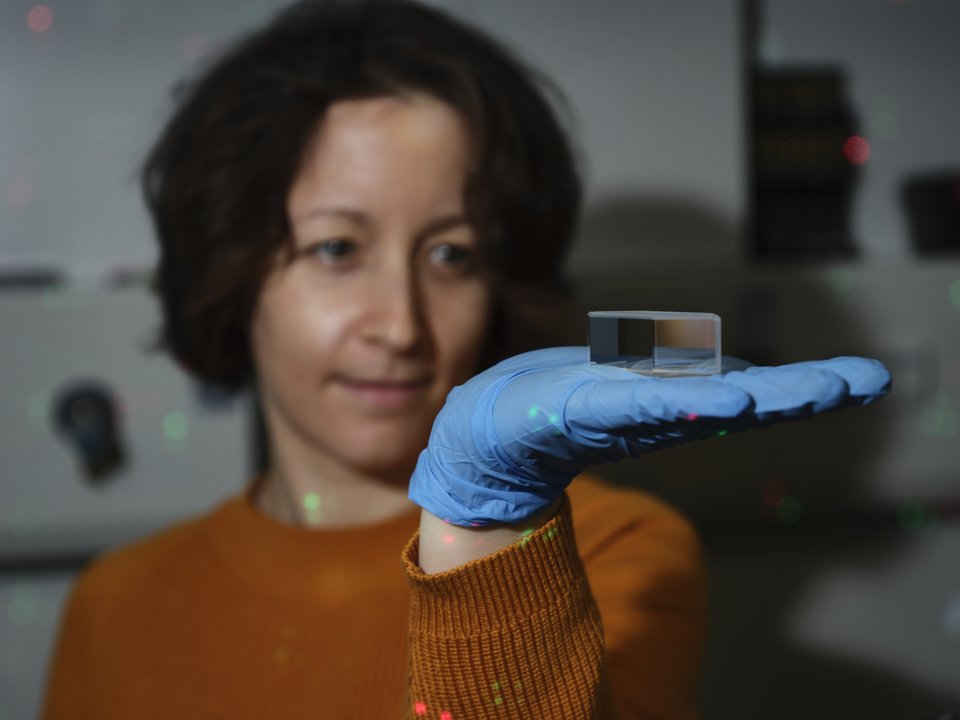

He demonstrates the Jerry Can Water Filter, a simple-looking water filtration system that you can screw onto almost any jerry can. With a sucking sound, the handle slides upward. When pushed back down, the spout spits out a jet of water. This working prototype is the result of years of designing, building and testing. It was a technical game with friction resistors, searching for a balance between the right filters and rubbers. After at least twenty prototypes, there is now a water filter that, in one smooth movement, fills a quarter of a glass with crystal-clear water.

Canal water instead of champagne

It began in 2015 with a graduation project by De Gruijter for his master's degree in Integrated Product Design. "I wanted to focus on a social problem. I was trained to make products, but I didn't want to design yet another variant of a coffee machine, there are so many already. The designer's paradox." So De Gruijter goes to see Dr. Jan Carel Diehl, assistant professor in the Design for Sustainability Programme at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering. Behind him hangs an assignment with a thumbtack on the wall: a small company in Amsterdam is looking for someone to design a water filter. This is how De Gruijter entered the world of water filters.

During the final presentation of his master's thesis, there was actually a working product in the room: a model with two buckets stacked inside each other and a filter in between, a completely different design from the Jerry. Prior to the presentation, De Gruijter fetched a bucket of Delft canal water. He dumped the brown, turbid contents whole into the top bucket. After exactly half an hour, the length of the final presentations, all the water had seeped into the bottom bucket. "I wanted to finish with a toast with water instead of champagne, to prove that it really works. My ninety-year-old grandmother immediately jumped up, wanting to taste it."

Filter washes itself clean

De Gruijter looks uncomfortable when he says that many products remain stuck in a concept and never see the light of day. In 2019 he therefore starts a business himself. Childhood friend Eise van Maanen also joins in, throwing himself into the financial side. Since then, De Gruijter has been focusing entirely on a new water filter and doing everything possible to actually get it to the people who need it. During trips to India and Kenya, he saw what a day's work fetching water can be. What struck him were the many jerry cans used to transport and store water, and so the idea of the Jerry Can Water Filter was born. A small handy filter that each user screws onto their own jerry can.

Inside the filter is a membrane that removes more than 99.99% of viruses, bacteria and parasites from the water. The only bottleneck with water filters is that they quickly become clogged with sand and dirt. Cleaning such a filter can be a complicated job. De Gruijter came up with the solution. With every pump movement, a little water automatically rinses in the opposite direction back into the jerry can, a backwash. This will automatically flush the filter. It sounds like a simple solution, but it was technically challenging. This solution makes the Jerry filter unique.

Wet pants

This design took off thanks to a collaboration with a group of students from the Industrial Design Engineering master program. In 2020, a total of twelve students collaborated to take the first design a step further. During the Advanced Embodiment Design course, they delved into the details of the design with fresh eyes, and many new ideas rolled out of that. The enthusiasm did not stop there, and several students extended their collaboration with De Gruijter and Van Maanen for the Joint Master Project.

Among them were Koos Berg and Anne Raspoort. They made new prototypes and were forced to stand in a six-square-meter room sawing and gluing because of the corona measures. The prototypes were tested extensively in the communal kitchen; it resulted in hilariously wet pants. "It's incredibly nice to be able to put a product together yourself from start to finish," Raspoort says. "But the prototype is never finished, it can always be improved," Berg adds.

Adventure in Ethiopia

Hannah Keulen and Sara Schippers also joined the project, focusing on user interaction. Jerry's intended users are not here in The Netherlands, however, where we can even flush the toilet with drinking water. To test the interaction reliably, the prototype had to go to an area where drinking water is scarce, the students argued. Thus began the adventure of getting a prototype to "the crossroads next to the church" in Ethiopia. Unfortunately, a full address did not exist.

There were contacts with BoP, an organization that supports companies to get their products into third world countries. "We couldn't go there ourselves, so we had to hand over both the product and the test, which was very difficult," the students recount. They also ran into cultural differences and the language barrier. "Apparently their package service apparently needs the phone number of the recipient, the most normal thing in the world there," laughs Keulen.

Fortunately, there was an alert employee of BoP, who traced the prototype at the local DHL distribution center. She was also the one who drove the filter through the dusty suburbs and congested main roads of Addis Ababa. She knocked on the doors of several families to have the prototype tested and take questionnaires. It was a success. One user called his four-year-old son, and a toddler immediately pumped a glass of water without difficulty.

With his Jerry Can Water Filter, Olivier de Gruijter became the 2019 Dutch national winner of the James Dyson Award, an international design award for problem-solving design talents. Thanks to this award, his design came into spotlight and new collaborations were born, such as Oxfam Novib and Cesvi, an Italian aid organization. Recently, childhood friend Eise van Maanen joined to make the Jerry Can Water Filter a success. Van Maanen has experience at the UN in several countries in Africa and was also already familiar with the water world. He is now focusing on the business side of the company.

Confidence in the product

A small amount of filtered water did squirt out of the nozzle with each pumping motion. "The prototype was not yet perfect; this was our well-known fountain effect," says Berg. Ethiopian test users saw it as a contaminated spill. "We learned that it has to work seamlessly, otherwise the confidence in your product disappears immediately."

The Palestinians will no longer encounter fountains in the latest version. The new filters will go to the headquarters of the aid organization Oxfam Novib in Gaza. Together with the Italian company Cesvi, they will ensure that the water filters arrive in the refugee camps. De Gruijter is eager to be able to hand over the first one himself. It remains to be seen whether the travel restrictions imposed by Corona will allow this.

In the meantime, De Gruijter is looking further ahead: "It has become more of a social and financial issue. As technical product designer it was a great project to work on, which is now largely over. But how do we get the filters to the places where they are needed most, in the most remote places of the world? We are thinking about continuing to work with aid organizations and using microcredit for the local people, so that they can buy their own filter. This is what I am thinking about with Eise right now."

The last filters go into the postal package and the box is taped shut. This time with a full address affixed on top.

Jan Carel Diehl

- +31 (0)15 27 89729

- J.C.Diehl@tudelft.nl

-

Room B-3-350

"To make design for the unknown known!"