Graduating among ancient objects at the National Museum of Antiquities. It’s not exactly what you might expect from a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering. But that’s precisely why Lucas, Martijn, Tim and Pim liked this final project so much. Using new photographic techniques, they tried to make ancient and faded Egyptian paintings visible again – and they pulled it off!

The students worked on their research on the Stele of Sehetepibreanch for almost six months, from planning to experimentation and from analysis to presentation. They worked closely with their supervisor Matthias Alfeld and a team from the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. ‘It was a unique experience,’ says Tim de Niet. ‘The stele we studied is part of the museum's permanent exhibition. The stele was cordoned off with tape and the museum was open, so we also got a lot of attention from visitors during our research.’

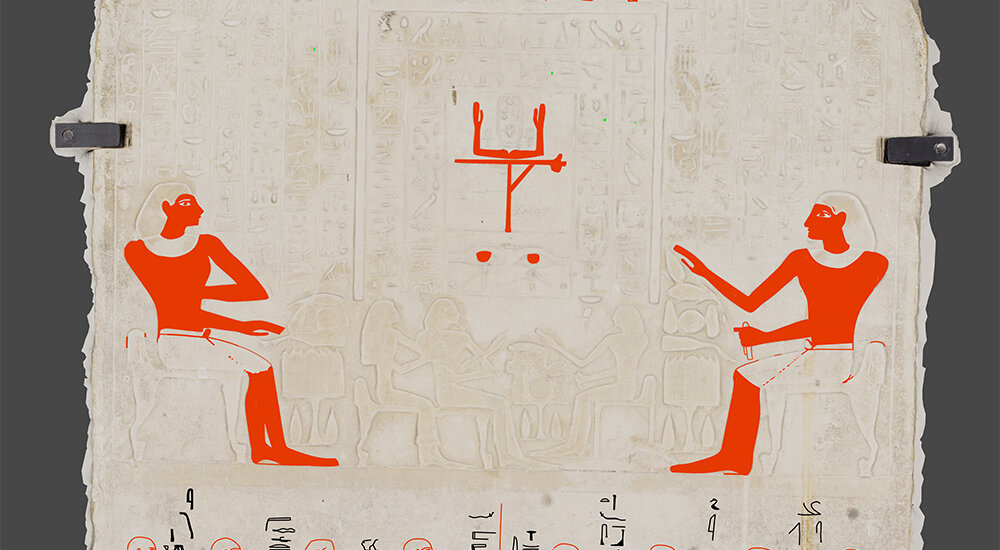

The Stele of Sehetepibreanch is 4,000 years old and was made to be placed near the temple of the god Osiris at Abydos. The stele, or stone slab with carvings, consists of three parts. The first part depicts King Amenemhat III as a falcon, while the second part shows the person who commissioned the relief, Sehetepibreanch, and his parents and brothers. The third part is completely blank, or so it seems.

Limestone and sandpaper

At the start of the project, the students spent a great deal of time mastering the techniques of Reflectance Imaging Spectroscopy (RIS) and contrast-enhanced photography with D-stretch. ‘These are good techniques for finding the underlying pigments that cannot be seen with the naked eye,’ says Pim Rijk. But they didn’t start working on the precious museum piece right away. ‘To familiarise ourselves with the techniques, we first made a prototype. We applied pigments on a block of limestone and then blurred them with sandpaper to carry out tests.’ This allowed them to find the right approach and perfect the techniques for the real work.

Expectations exceeded

The students visited the museum twice to photograph and scan the stele. The combination of photography, imaging and microscopy allowed them to digitally map the previously hidden pigments. Using the RIS technique, they took hyperspectral photographs. ‘As a result, these photos contain much more colour information per pixel than a normal photo,’ explains Martijn Swart. ‘We can then enhance tiny colour differences post-processing.’ D-stretch can then be used to increase the contrast. This gave the students a good idea of what was on the blank part.

In particular, the understanding of optics and imaging from the undergraduate course provided a good foundation for the development and application of the imaging techniques used

Tim de Niet

‘On the left side we could see three men and one woman, and on the right side three women and one man,’ says Pim. All the people were drawn in red and each had their name and title in black hieroglyphs. A trip into Egyptian history makes it clear that on the left is a priest called Senebef. Next to him is a guard, Wenneferoe. Also depicted is the mayor, Antefoker. On the right front is the only man in the group, someone called Amon, who was probably a priest. Next to him sits his sister, Senebes, with her daughter behind her. ‘The clarity with which we were able to make the paintings visible exceeded our expectations,’ says Lucas Zijlstra. ‘But unfortunately the hieroglyphs, which could reveal something about the relationship between Sehetepibreanch and his family with the people in this lower segment, are still not clearly legible.’

New knowledge

Although this was not a typical mechanical engineering thesis project, the students benefited greatly from the knowledge they had gained during their undergraduate studies. ‘In particular, the understanding of optics and imaging from the undergraduate course provided a good foundation for the development and application of the imaging techniques used. Skills in experimental design, data analysis and project management were also useful in this project,’ says Tim.

But the unique nature of this project also provided an opportunity to gain new knowledge. ‘Because this lies so far outside our area of expertise, we mainly learned many new things and ultimately gained a lot of information from the project itself,’ says Lucas.

From study group to group of friends

‘It was really cool to actually study a historical art object,’ Pim says. ‘Also, we discovered something that was unknown before, which was really special.’ The students say that the success of their project was partly due to the pleasant group dynamic. ‘In addition to working together as fellow students on our final project, we also became a group of friends who had a good laugh together. This made the whole process a lot more fun,’ says Martijn.