Every new green hydrogen plant is a 'world's first'

Green hydrogen will play a key role in the energy transition by largely fuelling non-electrifiable sectors such as heavy industry. Energy company RWE is involved in several innovative hydrogen projects and, although the hydrogen transition is facing delays, RWE’s Director of Hydrogen Netherlands Lijs Groenendaal remains unwaveringly optimistic. “A lot is going well.”

By Jurjen Slump • November 5, 2024

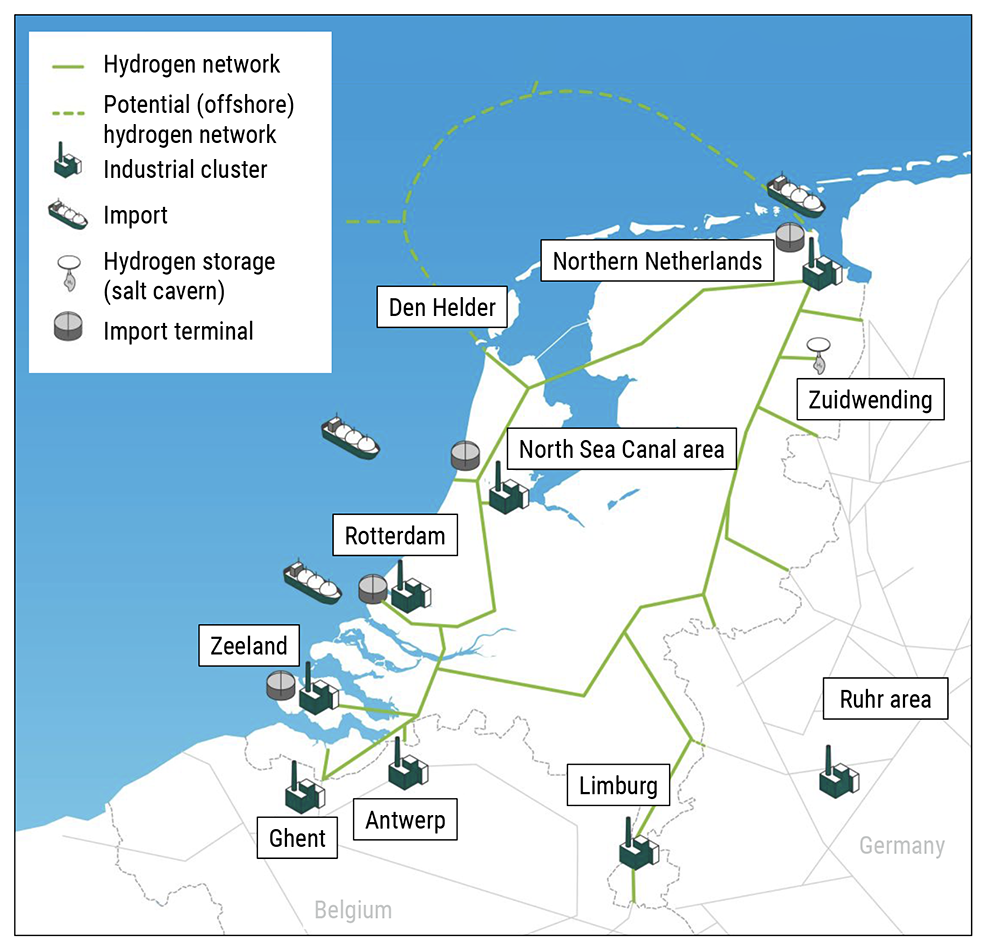

There’s certainly no lack of ambition. The goal for the Netherlands is to become a major European hydrogen hub, covering both generation and transport. Building and connecting various hydrogen networks - known as the backbone in the industry - should give the regional hydrogen market a major shot in the arm. Gasunie started building a nationwide hydrogen network only last year and promising agreements on the so-called Delta Rhine Corridor have been reached with Germany.

Gateway to Northwestern Europe

This corridor forms the backbone part between the port of Rotterdam and North Rhine-Westphalia, running through southern Limburg to provide renewable hydrogen to several industrial clusters along the way (Chemelot, Ruhr area). Industry's need for green hydrogen is so great that a significant proportion will be imported via the port of Rotterdam from where it will be transported to the German hinterland via the Delta Rhine Corridor. In Gasunie’s words, the Netherlands will become a “gateway for hydrogen to Northwestern Europe.”

But legislation and other practical hurdles stand between the concept and reality. Former Energy Minister Rob Jetten wrote to the House of Representatives this summer stating that construction of the Delta Rhine Corridor is four years behind schedule and the project is not set to be completed before 2032. The nationwide network will also be ready later than planned: not in 2027 but in 2030 at the earliest.

Lijs Groenendaal Lijs Groenendaal studied Petroleum Engineering in Delft between 1989 and 1996 before starting to work at Fugro, Total and Shell. Her work at Shell included developing Holland Hydrogen I, Europe’s largest green hydrogen plant, which is being built on the Maasvlakte. In 2023, Groenendaal joined RWE as director of hydrogen development Netherlands.

Eemshaven hydrogen plant

What are RWE’s views on the matter? “I’ve seen a lot of good things happen in recent years but I cannot deny that some delay has crept in”, Groenendaal explains. There are two main reasons for this. The first is infrastructure. “We are developing a large hydrogen plant in Eemshaven but how do you get hydrogen to big customers in Rotterdam if you don’t have the infrastructure?”

The second reason is policy. By 2030, producers will be required to blend green hydrogen with their regular hydrogen but the specifics are yet to be crystallised. The same producers, however, will need some degree of clarity about expected demand soon. “As this would enable us to start building and making investments”, says Groenendaal, urging the government to speed up. The key ingredient for accelerating infrastructure - and therefore the hydrogen transition as a whole - is large-scale purchasing. “Without demand, no supplier will build pipelines and plants.”

Rising network costs are also slowing down investment, with the expansion and reinforcement of the electrical grid pushing costs to a ‘multiple’ of the costs in neighbouring countries. “Costs are one of the reasons why green hydrogen investment has been slow”, Groenendaal concludes.

Scaling up electrolysis technology

Nevertheless, RWE is not sitting idly by. Until the national hydrogen network is ready, the company is working on 'energy islands' around industrial clusters such as in Groningen around Eemshaven. “There are always buyers to be found in these clusters, so we’re now trying to match supply and demand locally.”

The company is also extensively experimenting with new techniques to produce renewable hydrogen. This summer, the company opened an energy hub in Lingen just across the German border, with two different electrolysers that are tested in an industrial environment. The first electrolyser harnesses the principle of alkaline electrolysis (10 megawatts, consisting of four modules of 15 tonnes each), while the other uses a polymer electrolyte membrane (4 megawatts).

Battolyser Systems

The pilot plant in Lingen provides the company with a lot of expertise, required to scale up. As a ballpark figure, today’s hydrogen plants generate an aggregate of 300-400 megawatts but all the projects in motion today will end up totalling dozens of gigawatts, Groenendaal says. “However, everything still has to be built. There are no large electrolysis plants anywhere in the world yet. Every plant we build is a world first.”

Hardware innovations have been developed at breakneck pace in recent years. Among others, RWE is collaborating with the Delft spin-off Battolyser Systems, which has integrated a battery and electrolyser into a single device. The first demo system was installed at the RWE Magnum power plant in Eemshaven, and Groenendaal believes that this super-innovative technology will help solve grid congestion.

Link with offshore wind

RWE’s biggest customers will likely be companies that can electrify operations only to a limited degree, such as businesses in the chemical industry and major refiners like Shell, Total and Exxon. In the Netherlands, industry accounts for about 25 per cent of the country’s carbon emissions. The renewable hydrogen needed for the transition will largely be produced from renewable electricity generated by offshore wind farms, provided that some major technological hurdles can be overcome. “If you link electrolysers to a wind farm, you have to make sure that they can track wind turbine production. The problem is that wind farm output varies but customers often want a stable volume”, Groenendaal explains. “How do you make up for the difference between wind turbine production and customer demand? How much storage do you need? We’ll have to come up with very clever ways to make that link. You can simulate everything with software but actually getting it done is very complex.”

Smart innovations

Groenendaal also expects AI to play an increasing role in predicting supply and demand. However, there’s a lot of scientific research yet to be done, some of which is now being conducted as part of the OranjeWind project. Situated 53 kilometres off the Dutch coast, this wind farm is a joint project between RWE and TotalEnergies and is set to become a blueprint for the integration of offshore wind farms into the Dutch energy system. The company is testing numerous new smart innovations in collaboration with Dutch knowledge institutions such as TU Delft. After all, hydrogen will also play an important role in solving grid congestion. “Hydrogen converts electrons into molecules that can then be transported and stored, so it effectively relieves the grid”, says Groenendaal. “Electrolysis is an important part of good system integration.”

TU Delft - RWE partnership

TU Delft collaborates with RWE in various projects in the field of energy transition. In addition to OranjeWind, there is also a research programme led by TNO in the field of system integration and modeling of the Dutch energy system. In addition to RWE and TU Delft, Utrecht University, the University of Groningen and TU Eindhoven are also involved.

Two gigawatts of hydrogen by 2030

RWE is investing €55 billion in the energy transition worldwide until 2030. In doing so, the company that grew big on lignite will end up going green itself. RWE has already stopped investing in coal and is in the process of converting existing plants to biomass plants. “RWE's strength is that we offer all types of energy side by side: gas, biomass, coal until 2030 and increasingly wind, solar, hydro, batteries, e-boilers and hydrogen.” Its ambition is to be able to supply two gigawatts of hydrogen by 2030, a significant part of which will be produced in the Netherlands.

However, it will need to rely on others to help make that happen. “I don't think anyone can do this alone.” All key players in the sector, policymakers and scientists should continue to seek each other out and work together on innovation. “So my message is a positive one: lots of things are going well and we have reason to put our shoulders to the wheel together, starting regionally and scaling up once a national network has been pieced together. We just have to go out and do it.”

Interested in collaboration?

Interested in business collaboration or seeking knowledge and insights on your policy themes?

Contact us

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/_processed_/b/3/csm_HR_MKX05997_scaled_53b5d51bf2.jpg)