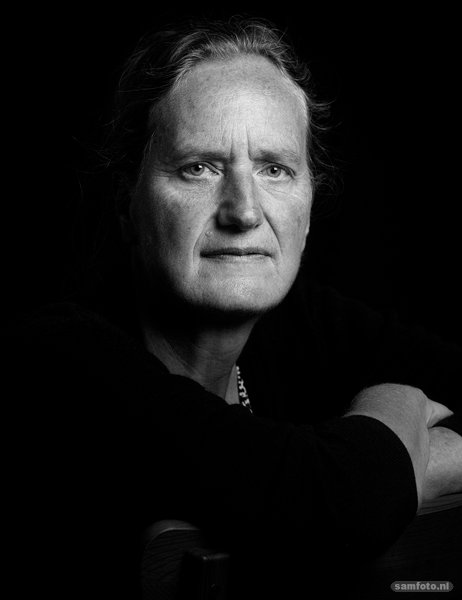

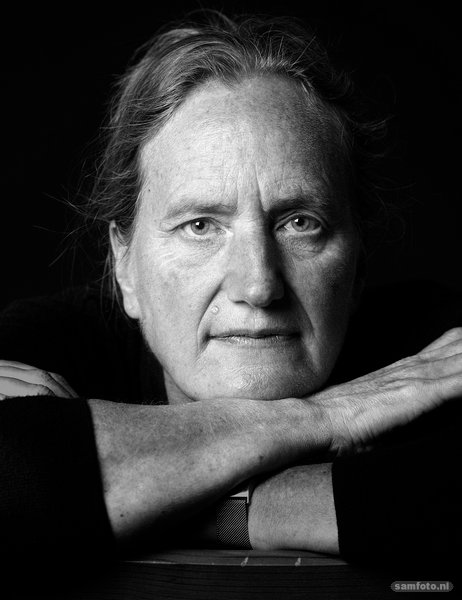

‘I learn a lot from my PhD candidates’

Professor Jenny Dankelman has been awarded the Leermeesterprijs. “I never thought I would become a professor after being advised to go to the home economics school.”

A professor that stands out in teaching and research is nominated by students and PhD candidates. Only a professor like that qualifies for the Professor of Exellence Award (a best professor award from the Universiteitsfonds Delft). Jenny Dankelman is awarded this accolade for her research into innovative medical instruments and her ability to teach.

What does the Professor of Excellence Award mean to you?

“It is a very meaningful award because I have been nominated by people with whom I work closely and that I try to help do their work as well as they can. Their token of appreciation is very humbling. It’s very special.”

What do you think you do to have won this award from your colleagues and PhD candidates?

“I think it’s mostly because I really enjoy teaching graduates and PhD candidates. I like helping them get the best out of themselves. And I also try to understand any problems that arise. My door is almost always open for them to just come in.”

the operating rooms as well and that you need to know exactly what they do there and why. He believed much more in my abilities than I did myself. I never thought that I would become a professor after the advice to go to the home economics school. Jos Spaan taught me how to set up research well. How to look critically at your data and how to write scientific articles. Kees Grimbergen introduced me to minimally invasive techniques.”

You graduated in mathematics. How did you end up in the medical world?

She laughs. “I never even dreamt that I would end up in the medical world, let alone learn surgery. It was a bit of a coincidence. While I was working on my graduation project, I was alerted to a PhD position in technical mathematics at TU Delft. I applied and thought that it would be useful to practice a job interview. I had never done one before. I took the first vacancy that appeared. It was research into the circulation of the heart muscle at Mechanical Engineering. It was an informal meeting and I was completely relaxed. Jos Spaan and Henk Stassen, the promoters, were keen and said immediately that the position was mine if I wanted it. I asked for two weeks to think about it. They subsequently sent me all sorts of articles that I could not even read because I did not know any medical terminology. In the end, I liked it so much that I decided to do it. I have never regretted it.”

Was it hard to connect the technical and the medical worlds?

“No, it was not hard; it just took a lot of time. You need to enter into each other’s fields, know the issues at play and learn the professional terms. You can help each other move forward as the medical field has a lot more technical resources available which clinicians need to learn to work with. Their need is more for new technical solutions. Minimally invasive surgical techniques entered the field at the beginning of the 1990s. From then onwards, these techniques are being used a lot more in operation rooms. Before that, it was not done much – surgeons could do a lot with needles and scalpels. Now the emphasis is to minimise damage to healthy human tissue.”

You are heavily involved in developing new curricula for master programmes. What do you want to pass on to your master students?

“Enough medical knowledge about anatomy and physiology. It is important to communicate well with medical people and to know their fields of expertise. This calls for time and energy. There are so many connections in this world. If there is something wrong with our bodies, we try to replace, support or cure something. You need technology to do this. We are trying to do more and more through small incisions with minimally invasive surgical techniques. Over the last five years or so, I have tried to encourage students and PhD candidates to do something for low-income countries. Do you know my story?”

“It was about women in Africa who were ostracised because they smelled. They smelled because they had been horribly raped and did not have access to surgery and were not treated. The article sat on my desk for weeks. I started to read more about it and found out that there are three million women with similar problems caused by protracted childbirths. The tissue in your uterus and stomach gets torn. I discovered that two billion people do not have access to surgery and five billion do not have access to safe surgery.”

Unimaginable …

“Yes. I felt that I had to do something. I submitted a project proposal to the Open Mind project at the Technologiestichting STW, but ended up fifth. At the time, Delft Global had just been founded. I submitted an application and could start with one PhD candidate. She had been to the African continent and was familiar with different cultures. She taught me – as you see, I learn from my PhD candidates – that it is important to know the context. You need to know what happens where. Another researcher that obtained his doctorate with me, told me that, after working in industry for four years, that he wanted to move to Nepal with his family. He asked me if I knew of anything he could do there. I had an idea and that was to see how we could improve the training of biomedical engineers and support medical technology departments in hospitals. Last year eight students went to Nepal, five to Kenya and three to Surinam. They are all working on hospital equipment.”

You put your efforts into women as you were one of the founders of the Dewis, Delft Women in Science women’s network. What was the trigger for you to do this?

“When I was first asked, I thought that I should refuse. I thought that it wouldn’t be my thing. I was used to being in a ‘man’s world’.

Were you afraid of being seen as ‘a complainer’?

“Yes. But when I was asked again, I thought why not? I have learned a lot from this experience, such as that it is important to know the differences in men’s and women’s behaviour. In December 1984 I was the Faculty’s first female PhD candidate. With hindsight I can see that I never was seen as ‘one of them’. You do your best to not stand out and to be one of them, but that gets very tiring after a while.”

What was so tiring?

“Letters that start with ‘Dear Sir’. Researchers are often anonymous and people thought that I was the secretary. Not that that’s bad of course, but if it’s not you, you don’t really feel comfortable. In the end I learned to recognise and understand the behaviour of men better. If you lead a group for example, and are facing a choice between A and B and you say ‘what shall we do, A or B?’, you are seen as not knowing the direction you need to go in. A man just says ‘shall we go for A?’ and if everyone says B, goes all out for B. It’s good to give people a choice, but it’s a more female approach. I learned to remain true to myself.”

You make a modest and somewhat shy impression. At the same time, you are hugely respected in the technical and medical worlds. What is your secret?

“To do my best. It is important to respect diversity. We need to be careful if we put our technical hats on and think that we can do things better. Technical innovation takes time. You need patience. I enjoy it and that’s maybe the most important thing.”