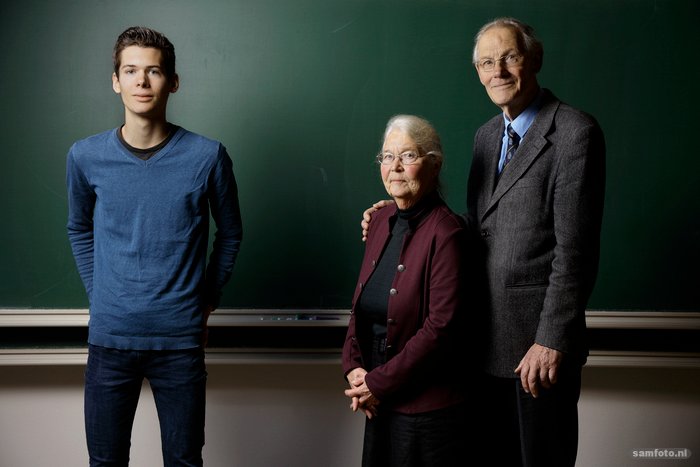

Following in his grandparents’ footsteps

Sixty years after Klaas Hoogendoorn and Maartje van Asperen started their engineering degrees in Delft, grandson Simon Gebraad enrolled at the university. We talk to two generations about the university, then and now.

Mr Hoogendoorn never would have thought that they’d be sitting here together after all these years. “On one of our first days at the Delft Institute of Technology there was a meeting at the Westerkerk. I saw her in the distance, talking to a classmate of mine. The weather was great, it was sunny. But she hadn't noticed me!” he jokes.

Yet they found each other, got married and had three daughters, all of whom graduated from TU Delft. Grandson Simon Gebraad is carrying on the family tradition. He is in his second year of Industrial Design Engineering and is a member of Civitas Studiosorum Reformatorum (C.S.R.), the association that his grandparents helped set up.

“My wife and I were both members of S.S.R. Delft, but we were unhappy about what was going on there,” says grandpa Klaas. “Thirty of us got together and founded C.S.R. We had twice as many members in the second year!” Now there are over three hundred, according to Simon.

Besides C.S.R., grandma Maartje was also a member of the Delftsche Vrouwelijke Studenten Vereeniging (DVSV), the female branch of the Delftsch Studenten Corps. “We often ate there together, because self-catering wasn’t an option then. You lived with a landlady and had no kitchen.”

At DVSV she had a lot of contact with national and international students. “There were girls from present-day Indonesia, the only international students I knew.” Things are different now, says grandson Simon. “It varies per course, but I think there are international students on about three quarters of the courses.”

In those days, the number of female students could also be counted on two hands. Grandpa: “No girls did electrical engineering. There were very few of them at all in Delft. There were six girls in the entire year group.” Grandma: “One in civil engineering, two in physics and three in architecture.”

She smiles. “That never bothered me. The lectures were enjoyable and I never had a problem. In those days it was unusual for girls to study. But now, in some faculties, women are even in the majority.” Simon nods. “On my programme it’s 50-50, but I think architecture has more women than men.”

Whereas his grandparents were still taught in barracks on Jaffalaan, Simon is taught in large lecture halls where professors share their knowledge using PowerPoint presentations. You can ask questions in between or during the breaks.

“We didn’t do that in our day,” says grandma. “During class, you listened and copied whatever was written on the board.” With chalk. So you had to write everything down before it was all erased.

Luckily, Simon’s grandma was very disciplined, says grandpa Klaas. He borrowed her lecture notes. “She was very good at taking notes.” Grandma starts to blush. “Someone had to copy what was on the board.”

But one thing never changes: the tension when lecturers announce exam results. Simon looks up all his marks online; his grandparents used to find them on lists hung up in the faculty. “At my department on Mijnbouwplein, the small hallway next to the receptionist was packed with students,” says grandma. “I couldn’t get near the list. Professor Druyvesteyn – an exceptional professor, according to Klaas – saw that I couldn’t see it and said: ‘Miss Van Asperen has a seven.’” She still seems proud of it today.