Whenever there is a problem with the Eastern Scheldt storm surge barrier, the Dutch get worried. The last time the barrier made the news was in 2013, when the stability of the barrier’s foundation protection was compromised.

What was going on? ‘Very strong currents can cause deep holes to appear in the Eastern Scheldt seabed. This increases the chances of damage to the foundations of the barrier,’ explains PhD Yorick Broekema. Now the stability of the barrier is no longer an issue. The Dutch water authorities are shoring up the side of the holes with rubble and steel slag, a steel works by-product. The formation of holes is also closely monitored and action is taken when necessary. ‘It’s my job to look for an ecological and sustainable solution so the people of Zeeland don’t get their feet wet,’ Broekema says.

The Eastern Scheldt storm surge barrier

The Delta Plan, which came in the wake of the catastrophic flood of 1953, initially proposed to close off all estuaries completely. It was widely criticised because the sea, while being a threat, was a vital part of the local ecological system as well as a source of income. As a result the design of the largest of the Delta Works’ dams and barriers, the Eastern Scheldt barrier, was changed. In 1986 water was allowed to flow into the Eastern Scheldt through openings in the barrier. When there is a danger of flooding the barrier’s sluice gates are closed.

Below the surface

The water enters the Eastern Scheldt at high speed – and consequently with considerable force. ‘That is something that was taken into account when the barrier was built. The construction is anchored firmly to the sea bed by five layers of mats, blocks and rubble which stretch 600 metres on either side,’ Broekema says. But the tidal current is proving stronger than expected. Directly behind the protective layer holes as deep as sixty metres are appearing. ‘A very deep, steep hole can produce enough pressure for things to start moving. The shifting sand can cause the protective layers to move as well and so cause damage. Eventually the barrier itself can become unstable and floods may become more likely,’ Broekema says. The formation of holes also threatens the stability of the surrounding sea dike and ports.

Plan of action

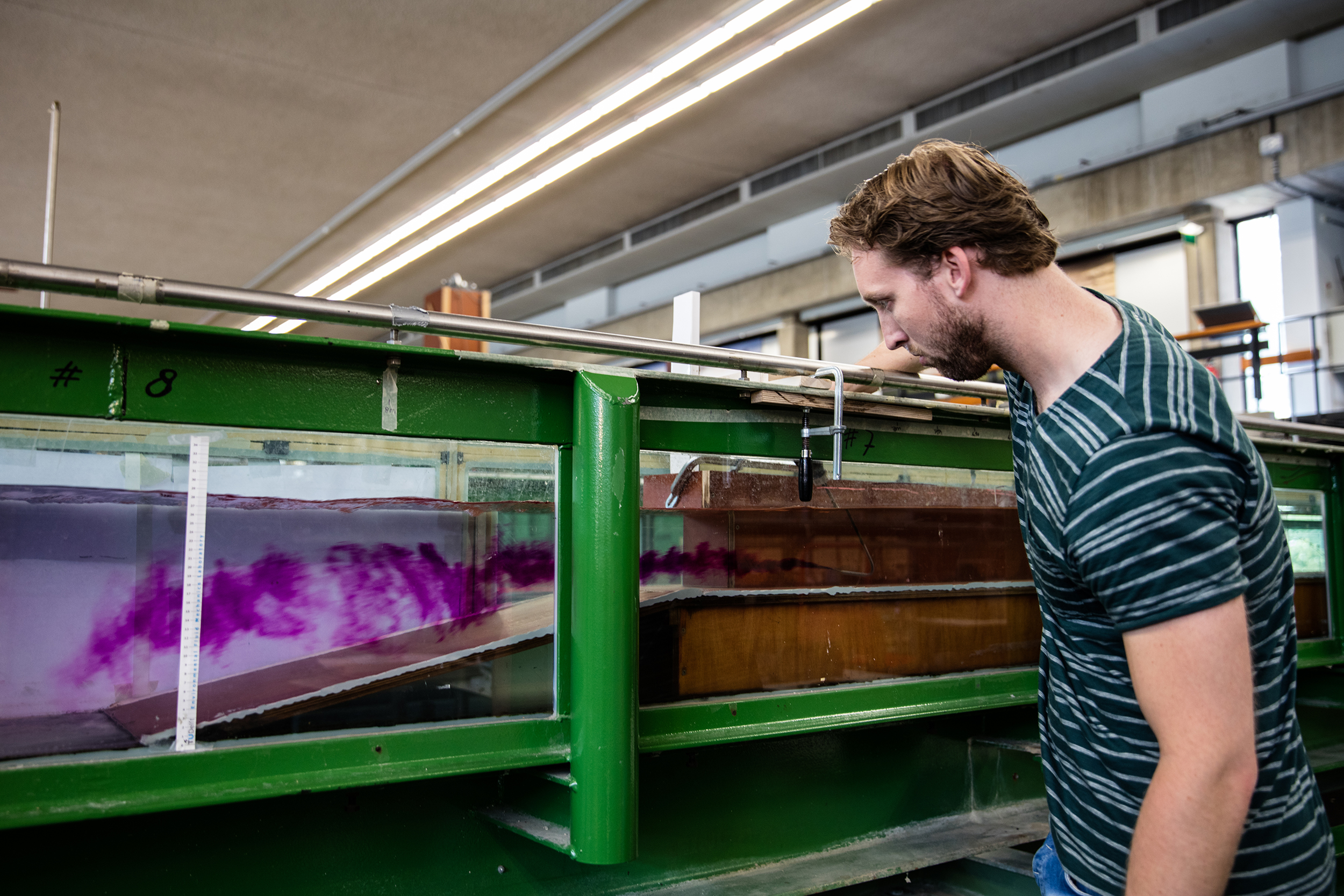

Broekema is investigating the cause of the holes: the turbulent tidal current in the Eastern Scheldt. The water authorities have provided him with an extensive data set of speed measurements of the current taken at different sites and depths of the Eastern Scheldt. At the Waterlab of the faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences Broekema is conducting experiments at scale to gain a better understanding of the process. In order to link the data from the data set to the results of the lab tests, Broekema is developing a numerical model. ‘This model will enable me to predict the effects of various ways to manage the current. The aim is to influence the strength of the current by means of small, local interventions so we can play around with it a little,’ Broekema explains.

Off the charts

Broekema has first-hand experience of the power of the Eastern Scheldt’s tidal current when he went out on a boat trip with some water authority officials. ‘We had to navigate our way into an area marked with safety buoys, which is normally off-limits. The force of the current took me by surprise. The boat had to lean in against the current in order to get to the right place. Sometimes the turbulence was strong it took the boat right off course so we couldn’t receive a signal on the measuring equipment. That’s where we found some holes in the data set afterwards.’

More about the flood of 1953 and the Eastern Scheldt storm surge barrier

In 1953 the combination of spring tide and a heavy storm hit the South West region of the Netherlands causing widespread flooding. The damage was enormous. Some 1,365 km2 of land was flooded, 1,836 people lost their lives and 100,000 people lost their homes. In order to avoid future tragedy the Dutch government came up with a strategic plan. The Delta Plan initially outlined a scheme to close off all estuaries. It came in for heavy criticism because the sea, while being a threat, was a vital part of the local ecological system as well as a source of income. As a result the design of the largest of the Delta Works’ dams and barriers, the Eastern Scheldt barrier, was changed. In 1986 water was allowed to flow into the Eastern Scheldt through openings in the barrier. When there is a danger of flooding the barrier’s sluice gates come down.