A small red car is driving in reverse, while a TU Delft master student is leaning out of the passenger window. “Left, right, more left. You got this!” As pot-holes and puddles are avoided, trees with giant thorns scrape off the car’s varnish. Water equipment, boots and a giant hedge cutter tumble around on the back seat as the car manoeuvres sharp turns. ‘’I think it’s after the third cactus to the right… I see it, I see the mill! We’re here!’’

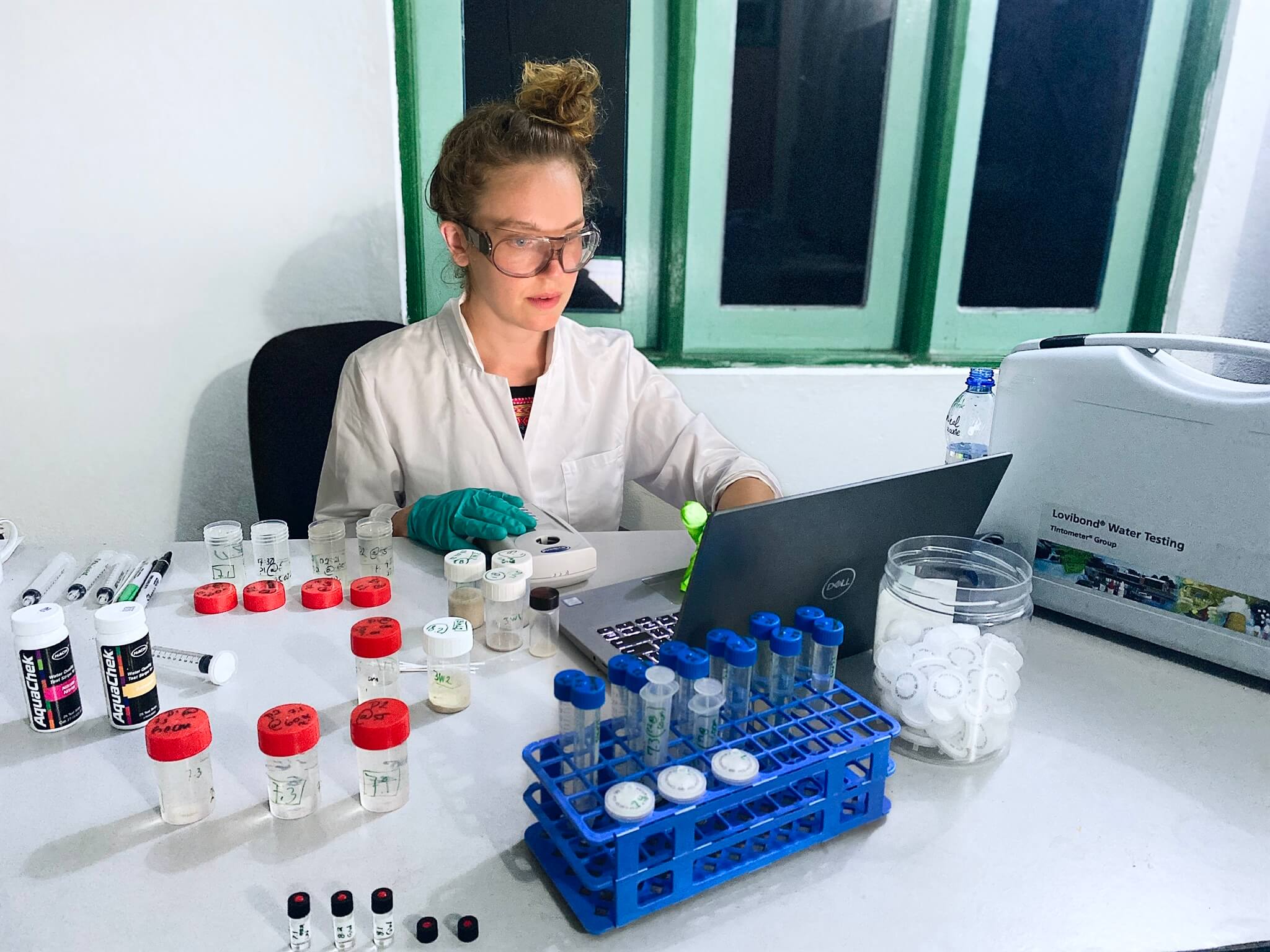

Environmental Engineering student Jessie-Lynn van Egmond is on a thesis adventure, hunting down old groundwater wells to analyse their water quality. So how is the island’s fresh water doing? Has it been subject to salinization or other pollution trends? That’s what Jessie-Lynn hopes to find out.

How did you end up going to Curaçao for your MSc thesis?

The original plan was to go to a small island in the Maldives for water research, but sadly this was not possible because of COVID regulations. For a long time it looked like there would be no fieldwork at all. Then it turned out that there was an island we could travel to, only it was on the other side of the world: Curaçao.

My thesis supervisor’s strong network in Curaçao, ensured that I could leave fairly quickly for the Caribbean. Our suitcases with water measurement equipment were already packed. So the only thing we had to do was change the plane ticket to Curaçao.

At first glance, you might think that there are many similarities between the Maldives and Curaçao, but other than the blue sea and sunny climate, it is a completely different setting.

The atolls of the Maldives are flat and often just a few hundred meters wide. Idyllic, with no cars, these 26 islands have a gentle culture with many Islamic and Eastern influences. Curaçao, on the other hand, consists of one island, and is a lot bigger and adventurous: there are lots of roads, cars, cacti, mountains, wild dogs and a Caribbean culture full of music. However, the water problems, on both the Maldives and Curaçao are very similar: think for example of groundwater pollution, intrusion of seawater at the coast, and coral that is deteriorating.

My MSc thesis was inspired by an old research paper from Utrecht University where 96 Curaçao wells were analysed on a range of water quality parameters. For my own graduation research, I hunted down the old groundwater wells to analyse the water quality. Data that is retaken at the same location and spans several decades is valuable to determine long term effects and trends. By taking new samples and comparing them to the data from the previous study, I could study the effects of salinisation and other long-term pollution trends the Caribbean island might have been subjected to.

What knowledge of your MSc programme could you apply?

For my master’s in Environmental Engineering, I followed specific courses on water quality which were essential for this research. During my master’s I also learned how to set up a well-founded data analysis, to make choices, improvise, and think on my feet.

Apart from this, I developed a certain mind-set. During my work as a student assistant, I learned about the importance of cultural nuances and sensitivity from TU Delft professors who were very much involved with the social side of technical and quantitative research. They taught me that local residents are the real connoisseurs of an area. We can learn as much from their stories as we can from the quantitative data we collect in the field. On top of that, building connections with local people can be essential, especially if you need to access sites on private property, as was the case on Curaçao.

What was the biggest challenge?

Although the deep-wells of Curaçao form a distinct part of its landscape and history, sampling them was much more difficult than imagined! The older wells were often covered by a typical Curaçao mill: tall metal structures that pump up groundwater for agricultural or domestic purposes. These mills were often abandoned, overgrown, covered, or collapsed. Others were on private terrain.

Another challenge were the long days. Sometimes, I would be going out at 6AM to take samples, and not finish the at-home analyses until 2AM. There were also several blackouts during our stay, which meant I was doing analyses in between candles, whilst trying to keep the samples cold with ice.

What is the most important thing you have learned?

I learned a lot about the subject of my master's thesis, the groundwater quality on islands. However, perhaps the most important thing I have learned is to never underestimated the power of kindness. The people of Curaçao are so warm-hearted and kind. They really helped in accessing wells; cousins were called to give an extra hand and together with locals we often found a way around the thorns and thicket. So supported by such a close-knit local community, uncharted wells became a family business.

What did you enjoy the most?

A lot, but the fieldwork by far the most: no day is the same, and it is so interesting to see what emerges from the first field measurements. It was also great to be outside a lot, to meet so many nice people and to be able to apply your knowledge in a practical way.

How will the research proceed?

My thesis supervisor is now researching Curaçao's groundwater on a larger scale with the Curaçao-based SEALINK project. The SEALINK project involves an interdisciplinary research team investigating how land-derived and waterborne inputs affect the growth and survival of coral reefs in the Dutch Caribbean. There will also be room for students to participate in the project!

What are your own plans after finishing your masters?

I am currently working as an R&D engineer in the horticultural industry, but I am also actively pursuing my own initiative: “Tewaii (Island & Water Research)”, which focuses on island & water research on the Maldives and other Small Island Developing States.

For those interested, definitely check us out at www.tewaii.com!

Jessie-Lynn van Egmond

Bachelor Programme:

Civil Engineering

Master Programme:

Environmental Engineering