If society is to embrace the principles of a circular economy, shouldn’t people themselves start fixing stuff and reusing parts on a much larger scale? But how do consumers become makers? These questions are the foundation for researchers Tanya Tsui and David Peck. Within the European Pop-Machina research project, they seek to enhance collaborative production within urban communities. They ask themselves: how can the maker movement take a pivotal position in the required transition?

“I am trained as an architect and used to work in Hong Kong, collaborating with NGO’s in China,” says Tanya Tsui. She now works as one a team of researchers on Climate design and Sustainability at TU Delft, who are trying to find means and methods to further a circular economy. However, most of the research in that area zooms in on technical solutions, reconsidering end-of-life solutions for buildings and building products. Tsui: “Societal solutions are equally important!” Moreover, proposed solutions are mainly business-oriented, aimed at generating commercial value on the basis of a different economic model. They result in businesses rather than consumers controlling the production and maintenance of goods. “Both me and my fellow researcher David Peck, are especially interested in how a circular economy has an impact on society. We try to address the knowledge gap by approaching the circular economy as an economy in which people rather than businesses are owners and manufacturers of products. Hence the name Pop-Machina, or People’s Machine.”

Momentum

Peck and Tsui consider the maker movement to be an ideal testing ground for a people-based rather than profit-based circular economy. The maker movement pursues the democratisation of the production of goods. Maker communities have developed a culture in which people themselves make and repair things, in so-called maker spaces. These are open workshops where anyone can rent or use for free the available tools and machinery as long as they share all of their knowledge with other users of the space. Relatively cheap and easy to use production technologies such as laser cutters and 3D-printers increasingly allow people to produce their own goods. Tsui: “The people who initiate and utilise these maker spaces already employ circular principles. They are however not necessarily directed at a more sustainable practice. Their knowledge and skills could be used to more effect, we think. Moreover, maker spaces are bottom-up initiatives, rooted in local communities. As such, they function as natural hubs in neighbourhoods for both industrial and social interaction. We asked ourselves: how can municipalities leverage on the existing momentum of the maker movement to transition towards a circular economy?”

Seven cities

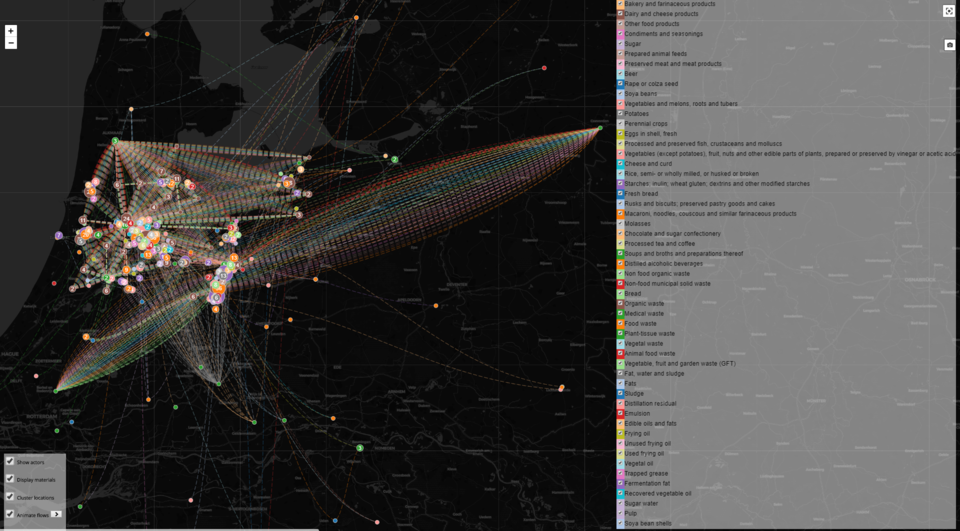

The intention is to develop circular maker spaces across Europe, in seven cities, in order to learn about both spatial and social aspects of community-based circular production. Urban planners, behavioural scientists, economists and legal experts from various universities are working in close collaboration with participating municipalities, from Venlo and Leuven to Barcelona and Istanbul. Other partners are consultants who provide expertise on particular subjects such as blockchain technology. Tsui: “We start out by defining the needs of the municipality and finding the correct stakeholders. Our role at TU Delft is mainly to design and run activities to engage the local community, such as workshops, and to provide local experts with an overview of the available tools.”

Among the project goals are teaching makers the principles of a circular economy, including design and entrepreneurial skills, and expanding the reach of maker spaces. “Pop-Machina should yield a digital platform which connects makers across Europe by allowing them to exchange knowledge and skills using blockchain technology.” Each city will also host some kind of physical space which sustains the circular transition, by connecting local people and local materials flows. “Leuven, which already has a strong maker community, is aiming for an urban materials depot. This is a warehouse that functions like a hub for swapping materials, parts and products. In Venlo, an organisation called KanDoen – CanDo – gives people with limited job prospects the opportunity to work for an income in their own neighbourhoods, thus encouraging social cohesion. This involves mainly manual labour. We are looking at ways and means to achieve a more sustainable practice in relation to the provision of meaningful labour.”

Prospects

One of several promising prospects, says Tsui, is the increased application of the principle of distributed manufacturing. This is, for instance, a producer of furniture ‘selling’ the design and outsourcing the assembly to a local maker community. “To me, the idea of having seven socially and culturally very diverse cities with populations ranging from 100.000 to 10 million people pursuing this common interest – a people-based circular economy – is incredibly exciting. It’s going to be a challenge to assess all the different results in the various pilot areas. I am confident they’ll contribute to a people-based rather than a profit-based economy.”