It is not uncommon for tools to be developed for research projects, but the tool to emerge from REPAiR (REsource Management in Peri-urban Areas) is one to be particularly proud of. And this is not only in the eyes of TU Delft researchers Alexander Wandl and Arjan van Timmeren. “Local and regional authorities in both Europe and the United States can't wait to start using it.”

The research proposal from 2017 shows real promise. A multidisciplinary research community which includes IT experts, environmental scientists, administrators and spatial developers will be working in six European metropolitan regions to collect and interpret information on waste and resource flows. Authorities, businesses and other stakeholders operating at different scales are bringing their current local and regional issues to living labs, as well as their expertise. The project is clearly focused on interaction between theoretical research and daily spatial-economic practice. Main goal: to develop an instrument that can produce an accurate analysis of these flows, that is coupled to activities and that enables users to develop spatial strategies that lead to more sustainable resource chains based on circularity.

Material flows

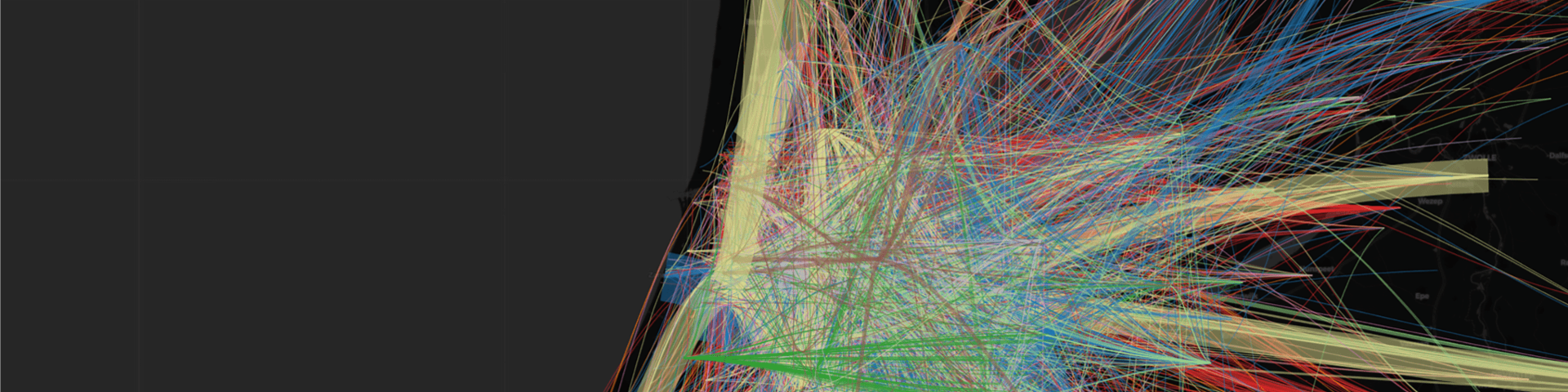

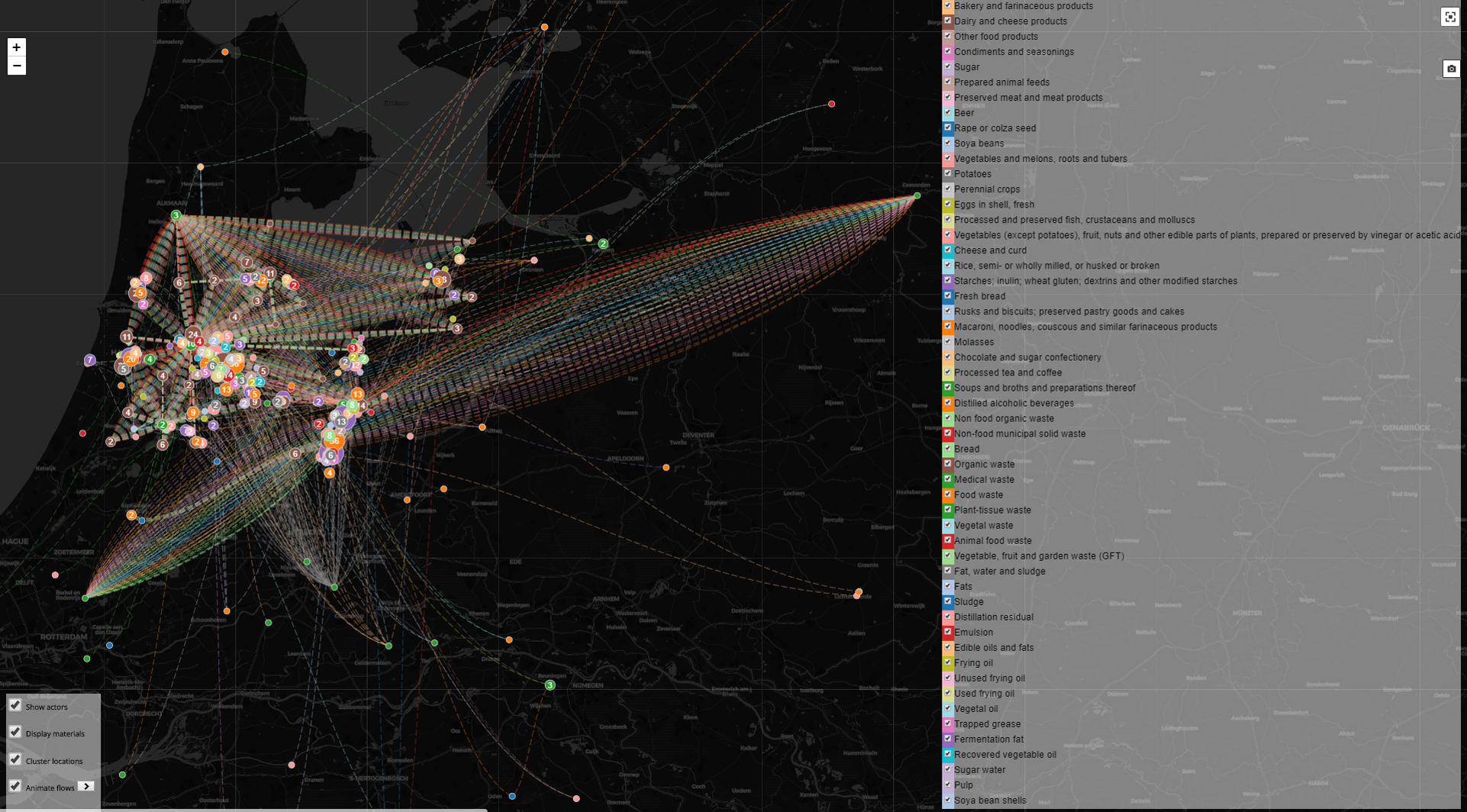

Four years later, project coordinator Alexander Wandl produces a geodesign decision support environment (GDSE) on his laptop, as if by magic. Dozens of criss-crossing lines and bars in primary colours show how many resource and waste flows go in and out of the six regions, and what routes they take. You can select individual materials and material groups, and zoom in right down to address level. “For all six regions, we have mapped out waste flows in the food production and consumption chain. Moreover, local information needs are included for each metropolitan region. For Amsterdam, this means we have mapped out construction and demolition waste flows, while for Naples the priority was environmental pollution flows. The tool gives at-a-glance information about where the causes and consequences can be found.”

Wandl feels that REPAiR's ability to interlink spatial planning with the technical, economic and governance aspects of a circular economy is hugely important. Landfill sites and waste processing plants tend to be found on the outskirts of the city, where industry and large-scale traffic infrastructure also take up a great deal of space. These peri-urban areas between city and countryside have now been largely earmarked for housing. So an essential question is: how can we maintain space for diffuse, circular activities and to what extent can we match these with existing or intended functions? Wandl: “Proximity of activities is crucial for a circular economy. So you want to avoid any planning which doesn't take account of this or where everyone then says: ‘That's great, but not in my backyard’.”

Orange peels

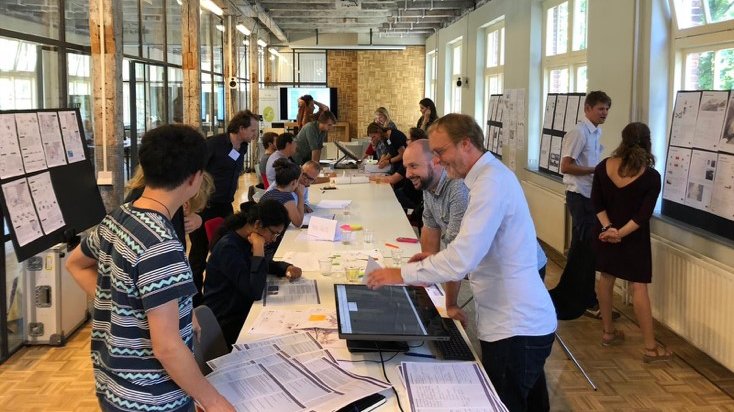

During the workshops with local partners, many new ideas arose thanks to the visual ‘evidence’, says lead researcher Arjan van Timmeren, Professor of Environmental Technology & Design. “Someone sees that the waste produced in their municipality includes tons of orange peels, and comes up with the idea that they could be used to make coffee cups or soap.” ‘Circular’ is not always by definition ‘sustainable’, he adds. “It is very possible that recycling requires so much energy that it increases the impact on the environment rather than reducing it. This is why we have linked a life-cycle analysis to the REPAiR instrument which you can use to verify whether a potentially sustainable change in the materials/resource chain really will be better for the environment.”

Strict agreements

An instrument is only as good as the data fed into it. Van Timmeren explains that the access to non-public data upon which REPAiR is based is a decisive factor in the instrument's success. “In Europe, every legal entity is obliged by law to report all activities related to waste management. For example, the Netherlands has the National Waste Control Centre (LMA). All data concerning the transport, storage, processing etc. of waste is kept in huge databases.” This information is mainly used to ensure the proper handling of hazardous materials, and that's about it at the moment. For REPAiR strict agreements have been made concerning how we can use this sometimes privacy-sensitive data. Linking this to other data sets results in a rich source of new, socially useful knowledge. “Once you are able to identify waste sub-flows, you can begin to think about how you can move from a linear to a circular production process. The high density and quality of the data are at the heart of REPAiR's success.”

Impatient

Even though not all the underlying data is public, the tool itself is open-source software. And the project partners are considering how the data can be used without compromising privacy. So it's hardly surprising that government bodies are impatient to start using the tool. At present waste flows in ten European metropolitan areas have been charted. According to Van Timmeren, the City of Amsterdam wants to use the tool to chart all the city's current waste flows, to use as a baseline measurement for the transition to a circular Amsterdam. And the same is true of Brussels. “We are discussing possible applications with New York and Baltimore and the National Waste Control Centre has indicated its desire for this information to be available for more areas in the Netherlands.” REPAiR now has a successor: the European research project New Circular Economy Business Model for More Sustainable Urban Construction (Cinderela), which is aimed at reducing waste in the construction chain. Meanwhile, two PhD researchers have started a company. Van Timmeren smiles: “We won't get bored any time soon.”

More information

- Project REPAiR