China is tackling its climate challenges with a national programme for making outdoor spaces adaptive. The so-called 'National Sponge City Programme’ is a good step forward, according to PhD student Meng Meng, but it also requires adaptability from the planners and authorities.

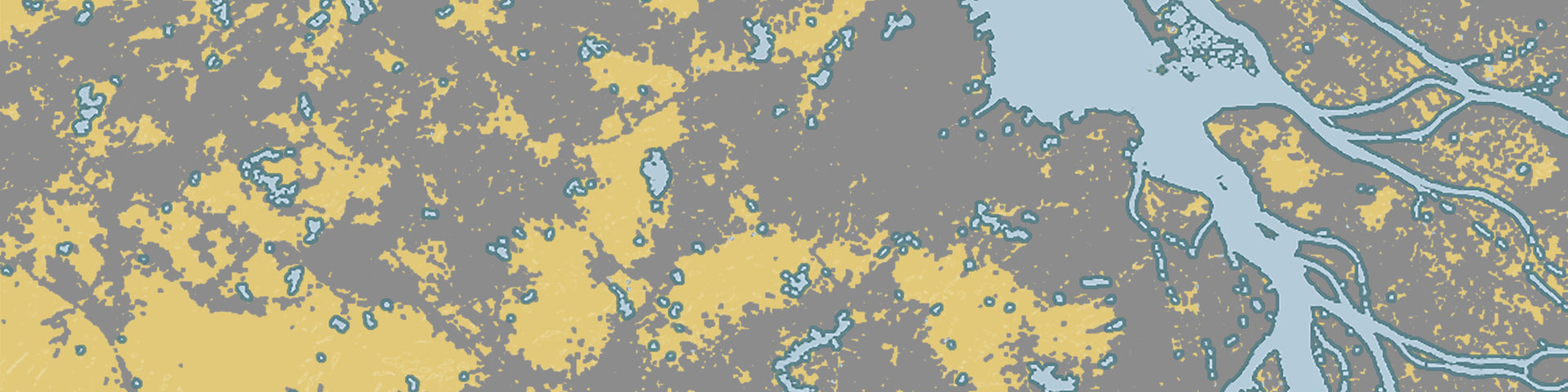

For the delta region around Guangzhou, which is the focus of Meng Meng's research, improving flood resilience is of vital importance. About 64 million people live in and around the metropolis. They will inevitably be confronted with flooding if the sea level continues to rise and extreme weather often occurs more often. "But to increase flood resilience, favourable institutional conditions must first be established," Meng summarises the results of research. "Otherwise it will be difficult to implement new spatial strategies."

And that is more easily said than done. Historical research that he did into the period 1920-2010 shows that water safety in China has always been a matter for engineers. By constructing dikes, sewers and pumping stations, they managed to control threats from the sea, the river and the sky. The contribution of urban planners to dealing with the threat of water was limited; they designed their highly densified cities as if there were no flooding threats. Meanwhile climate change is increasing the chance of flooding.

The recent rollout of the "Sponge City" programme is forcing a change in that strategy. This model involves the strengthening of the ecological infrastructure, preservation of wetlands and green zones and the setting up of water buffers. It also aims to make cities more attractive.

Momentum

Pilot projects have now been started in dozens of cities, with varying degrees of success. Building sponge cities requires large investments, but enough money is not always available. In addition, there is an institutional problem: authorities are not equipped for modernised, dynamic planning systems and the use of advanced techniques for forecasting floods. Among planners, knowledge is lacking, and decision-making often still proceeds in the old-fashioned "vertical" way. The result is that many urban planners still continue to work the way they always have.

In Guangzhou, government support is introducing some momentum to the realisation of the local Sponge City Plan (2017), according to Meng's research. A special subject plan and horizontal collaboration between the planning and water management sectors are resulting in more integrated urban planning. This should create more space for good drainage, smart zoning, improvement of the green-blue infrastructure and - if necessary - construction of physical flood barriers in dry areas. This will result in areas clearly being better prepared for extreme weather conditions.

Despite the improvements, Meng still sees many “institutional” barriers here. This has to do with the organisational structure and the rules of the game. There is agreement that spatial planning must change, but the influence on policy-making is still faltering. What needs to be done differently? Procedures must be overhauled and the financing of climate policy must be improved. But a change of mentality is also needed, he concludes from answers collected from respondents. Not everyone fundamentally believes that a new approach can help. “Changing the rules is just the beginning,” says Meng. “People also need to understand why planning needs to be done differently: this is where education comes in.”