Project Ruralization has just concluded. Over the course of four years, partners from 12 EU countries examined how best to revitalise Europe's countryside. Professor Willem Korthals Altes from the faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment directed the entire project. Additionally, he enlisted his personal expertise to answer the question: to whom does farmland belong and what should be done with it? "Farmer is essentially the only remaining hereditary profession in Europe: you become a farmer because that's what your parents are."

The summary of project Ruralization contains the following description of the state of rural areas in Europe, written by Dr Titus Bahner of Kulturland.

“On average, the European countryside is depopulating. Young and qualified people are moving to the cities, and the old are left behind. Schools and shops are closing, doctors leave, public transport stops. Cultural events are declining. It is a vicious cycle.

Moreover, the landscapes are now monotonous. Meadows were drained, hedges cut down, birds and insects decimated. Small farmers are giving up and large farms keep growing. Machines are controlled by satellite and farm animals are hidden away. Fewer and fewer jobs are available.”

Unsurprisingly, in 2018 the European Commission called for a consortium to study and counter this 'vicious cycle'.

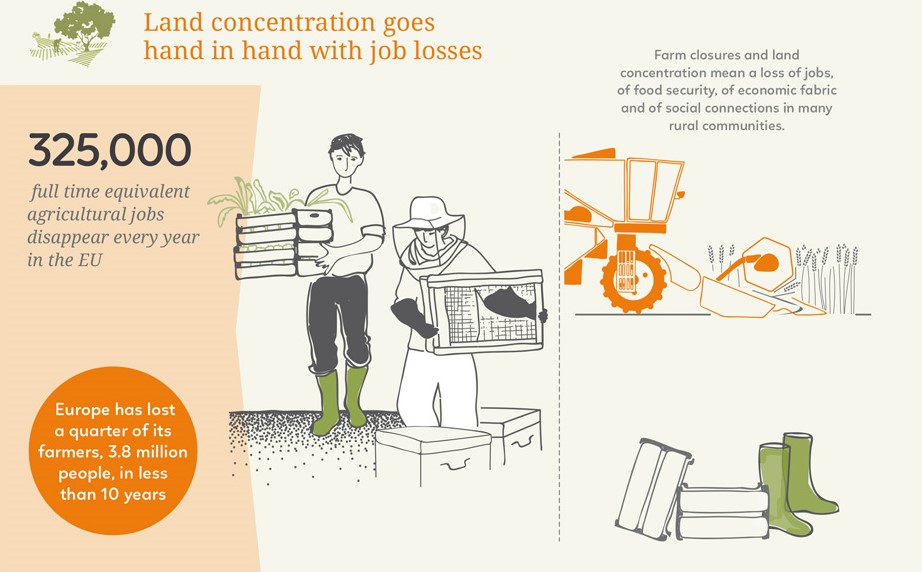

Ruralization highlights that the EU lost nearly 4 million farming jobs in a decade. Infographic by Access to Land, illustration by Camille Lucas.

A team assembles

Willem saw the call posted on the European Commission's website. "Our faculty mainly responds to urban-oriented projects, but agriculture is very important to the EU." Writing a proposal is a lot of work, so Willem had to weigh up whether there was a chance of success here. "I felt there was. The ageing of rural areas, the opportunities of the new generation, we can work on that. And access to land for new generations, that's land policy! I can contribute to that topic myself."

The first step is to look for partners. Willem got in touch with Terre de Liens in France, an organisation that provides help to new farms. One of its leading figures is a man who rowed for the Netherlands in the 1964 Olympics. "He was actually immediately sold." Through a publication, Willem found an organisation in Finland that researched exactly what he wanted to know: what do young people want? "I just sent the director an email. They immediately delivered a whole work package! They suggested comparing young people's wishes with actual demographic trends." Slowly, the team came together: by the time the proposal was submitted, Willem had already found partners in more than 10 countries.

Who is Willem?

Willem Korthals Altes is MBE professor. "My subject, in short, is land policy." By which he means the planning and management of the physical space where we live and work. It involves the interaction between market and policy, both in urban and rural settings, the legal aspects, and the value of land and what is on it. "Land is interesting, as it is both a way to invest and an essential need. As such, land is often a source of conflict when desires and practice clash."

A plan is drawn up

At the kick-off meeting, the consortium had already decided to focus on four pillars: young people's aspirations, local initiatives, policy (including EU agricultural policy), and access to land. For the first pillar, they mapped young people's dreams for the future in 20 regions across 12 EU member states. Workshops were held with for instance local policy-makers to explore what is thwarting these dreams. The regions were revisited a year and a half later to further determine obstacles.

The researchers interviewed people involved in 30 local initiatives, started for three different parties: newcomers to the rural area, new farmers, and farm successors providing agricultural renewal. They also started a study on EU agricultural policy, specifically on generational renewal. How have different member states taken this up and shaped it? And finally, a study was conducted on how newcomers gain access to land, in terms of policy, market developments, and 64 social initiatives. A number of possible new initiatives were then further developed.

Adversities and discoveries

Shortly after the project started, corona took the world by storm, and all workshops and interviews were required to be online. This did make the social part of the project very difficult. Willem: "A lot of people suddenly had to look after the children, which made organising a lot harder. The only bright spot was that we could really focus on this project. Ruralization gave us a purpose." In retrospect, he is very grateful to the local team leaders for keeping up the courage; they saved the project. "And it was incredibly gratifying that we could see each other again at the end of the project, that felt like a party!"

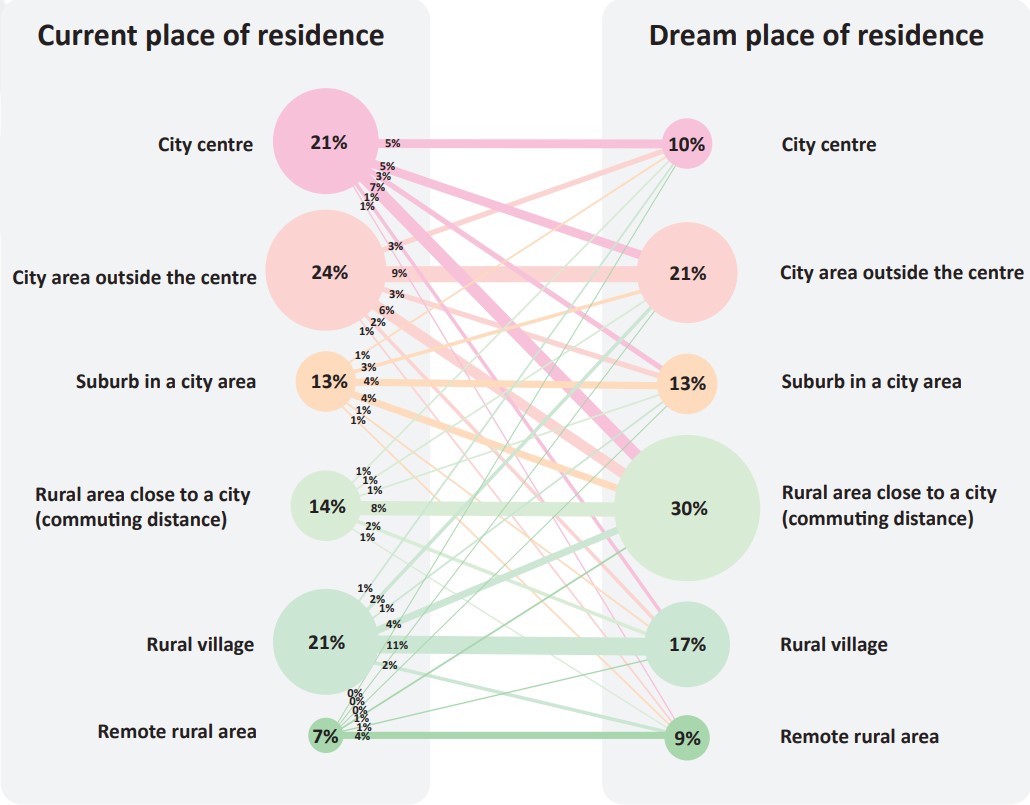

Time and again, researchers found that many young people in cities wanted to live more rural. (Graph by Prof. Tuomas Kuhmonen)

During the project, the researchers received many positive reactions to their approach: addressing young people directly and asking for their wishes. Willem: "It's actually crazy that this is seen as innovative, but better late than never." An interesting finding that emerged early on is the discrepancy between the wishes of young people, who often say they want to live in the countryside, and increasing urbanisation. Researchers in France, Poland, and the Netherlands were each taken by surprise.

How should we continue?

The outcomes of Ruralization are depressing and hopeful at the same time. Willem: "There are initiatives for local participation in agriculture everywhere. But they are still very much on the margins... Let's make them widespread!" He did not seem particularly positive about how EU agricultural policy was taken up. There are almost no policies anywhere to give new farmers access to land. "Agriculture in the EU has been so focussed on scaling up and automation, and a lot of nations seemed to say: we will just continue on this outdated course."

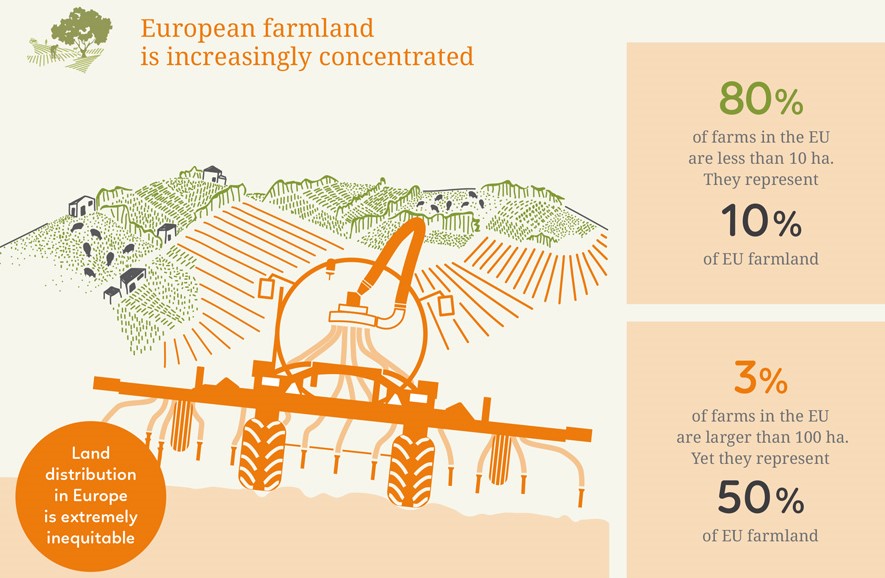

Ruralization shows the huge inequality in the EU between small and large farms. Infographic by Access to Land, illustration by Camille Lucas.

It was disappointing how deep gender inequality persists in farming. In the Netherlands, only 5.6% of farmers are women, many of them over 65, and they own only 3.4% of the land. Willem: "This is in line with the old tradition that, as a woman, you only receive a farm if you become a widow." Fortunately, several gender equality initiatives have already been launched by Ruralization partners, for example the FLIARA project supported by our faculty.

The Netherlands is in bad shape, but we can address that. Willem: "Look for example at France, many school canteens there deliberately serve local products." He says more farmland should be used for local production instead of the global market. "Rural land is certainly already a priority in the Netherlands. The belief used to be: what is good for the agricultural economy is good for a vibrant rural area. But we now know that this is outdated thinking, and it is time to act accordingly."

Published: November 2023