Resident groups in Cairo are increasingly active in neighborhood management, with varying degrees of success. Officials welcome their participation but often lack the resources to act on it, Aya El-Wageeh notes in her doctoral research. There is also a lack of formal channels for local activists to turn to. “If these active residents are given room for participation, it could unleash great potential." says El-Wageeh.

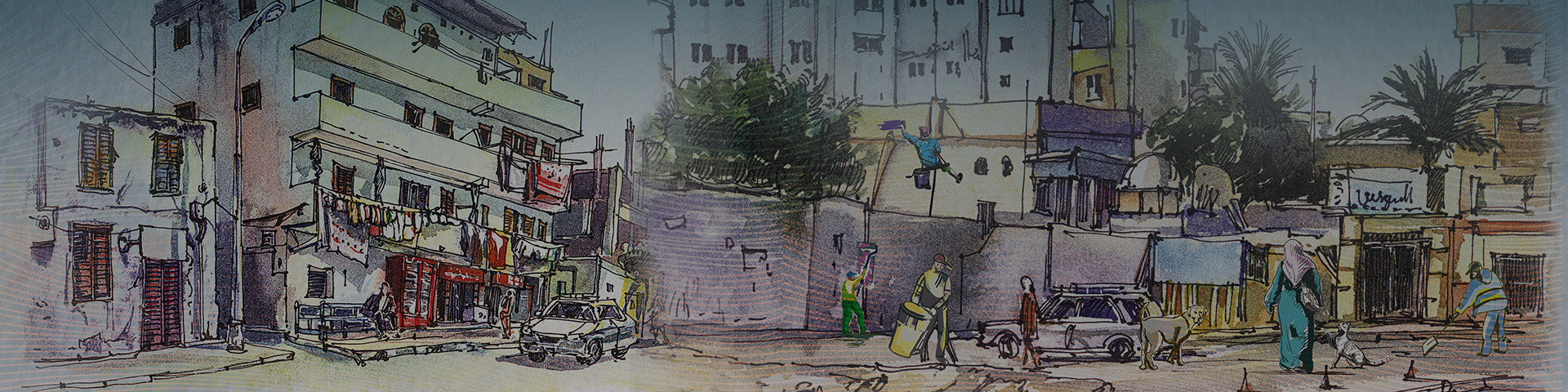

The 2011 revolution was the immediate trigger for residents’ increased involvement in their neighborhoods. When central authority temporarily fell away, groups of residents rose up to collectively tackle insecurity and other problems in their streets. After stability was restored to the country, in many cases such neighborhood watch groups grew into a kind of residents' committees. They tackle deterioration in their neighborhoods, build urban gardens or raise it with the local authorities when there are potholes in the road, missing pavers or broken sewers.

‘Fixer' groups for urban improvement

Since many of the residents' groups report their activities on Facebook, El-Wageeh was able to approach them. "The vast majority of them function purely as 'fixer' groups," she observes. "They are concerned with solving physical problems in the physical realm of the city, with no political ulterior motives."

She succeeded in contacting fifteen resident groups from nine different city neighborhoods that are committed to urban improvement. The size of the groups ranged from a few hundred to thousands of neighborhood residents. She also had interviews with both participants from neighborhood committees and officials in charge of neighborhood management. These show that residents are eager to get actively involved in making their districts better and feel more involved in their neighborhoods, even if by no means all their wishes are granted. Often the money to build a neighborhood park or improve an intersection is lacking, as the central government prefers to invest in new cities.

Urban planning is more than building new houses, neighborhoods and cities. It is also about making the existing city function well. This requires the input of everyone.

Aya El-Wageeh

Lack of official channels

Local authorities welcome the extra hands and ears, interviews reveal, because they face chronic understaffing. They therefore like to use the "multidimensional" knowledge of citizen committees. "Unfortunately, only rarely does residents' input end up at the urban policy level, because the official channels to do so are lacking," El-Wageeh observes. "That's a missed opportunity. If these active residents are given room for participation, it could unleash great potential."

She therefore advocates more residents’ participation and the establishment of official channels where neighborhood groups can go with their complaints and suggestions. In addition, more opportunities are needed to hold local authorities accountable if problems are not solved. An ombudsperson could play that role.

Furthermore, not all communication should be through unofficial channels, such as Facebook and WhatsApp. Her findings highlight the need for an official framework for communicating binding decisions and for incorporating the input of local activists into urban policies. It should ensure that deployed policies do not stall if one cooperative official disappears. Moreover, it could help address structural urban policy failures that are the root of many problems.

Together, the proposed measures could form the basis for greater livability in a megacity like Cairo, El-Wageeh believes. "Urban planning is more than building new houses, neighborhoods and cities. It is also about making the existing city function well. This requires the input of everyone."

Published: July 2023