Design foundations for education

When designing education, there are numerous science informed principles you can apply to make your teaching more effective. Here we will focus on three of these principles that fit the educational vision at TU Delft; constructive alignment, student centred learning, and active learning. We will discuss briefly what these principles mean, why they work, and how you can apply them.

Where these principles stem from

Educational psychology distinguishes two broad models in learning: objectivism and constructivism (Jonassen, 1991). Objectivism states that information exists as an individual entity (object) that is unrelated to the ‘knower’ that can be transferred, whereas constructivism stresses the individual construction of knowledge based on individual learning processes and the unique, personal experiences of the learner (Duffy & Jonassen, 2013). Constructivism has been adopted as the leading paradigm in most learning frameworks (e.g. Biggs, 1996), stating that the effectiveness of teaching depends on choosing appropriate teaching and learning activities.

The principles discussed here all fit within constructivism. They give guidance for aligning and choosing teaching and learning activities to support individual learning processes. Starting with the principle that is both easy to grasp and essential: constructive alignment.

Constructive alignment

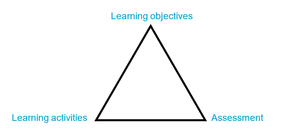

Constructive alignment (Biggs, 1996; Cohen, 1987) places the student at the centre of the learning process and considers learning to be efficient when the learning activities (what students do) and the assessment (what students are assessed and receive feedback on) are in line with the learning objectives (what students should learn). A mismatch in any of these pillars will lead to less efficient learning, as students will not learn what they are supposed to.

Although this sounds obvious, it is easily forgotten. Making it a conscious decision to check and review this alignment is recommended when creating learning objectives, designing learning activities, and setting up assessments. Are the learning objectives complete? Do you assess all learning objectives? And do the learning activities you offer cover all learning objectives? You might want to use a so-called constructive alignment table to create an overview of learning activities and assessments per learning objective, to make sure all align.

Aside from this alignment, putting the student in the centre of the learning process also has other implications for the design of learning activities and assessment, described by the next principle: student-centred learning.

Student-centred learning

Student-centred learning as a concept comes from the conclusion that although traditional, teacher-centred lectures are efficient, they are often not very effective in terms of actual learning and motivating students to learn (Armbruster et al., 2009). In contrast, student-centred learning focuses on promoting active learning and motivating students to take responsibility for their own learning.

These differences between student-centred and teacher-centred learning can be described on the basis of five indicators, see the table below (Wright, 2011).

Indicator | Student-centred | Teacher-centred |

1. Balance of power in the classroom | Students are given freedom in what, when, and how they learn. | All decisions are made by the teacher. |

| 2. Function of course content | Course content is a means to an end, the focus is on meeting course objectives. | All course content needs to be covered in class. |

| 3. Role of the teacher versus the role of the student | The lecturer coaches the student to guide their intellectual development journey. | The lecturer is a “sage on the stage”, seeing the student as empty vessels to be filled. |

| 4. Responsibility of learning | Responsibility lies with the student. | Responsibility lies with the teacher. |

| 5. Purpose and processes of evaluation | Evaluation promotes learning | Evaluation generates grades |

Active learning

Active learning is commonly defined as any instructional method that engages students in the learning process (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). When active learning is applied, students are actively gathering knowledge instead of passively receiving it. This leads to a more engaged form of learning and to more attention from students (Freeman et al., 2014).

The key to active learning for educators is not to just tell, but to ask questions, and let students find out for themselves by offering a range of interactive learning activities where students learn by doing. For more guidance on applying active learning in your classroom, please refer to the design a learning activity page.

How to get help

Do you have any questions about these principles? Reach out to the educational advisors at your faculty or contact Teaching Support for 1-on-1 guidance.

References

- Armbruster, P., Patel, M., Johnson, E., Weiss, M. (2009). Active learning and student-centered pedagogy improve student attitudes and performance in introductory biology. CBE Life Sci Educ. 8(3), 203-213.

- Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher education, 32(3), 347-364.

- Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. 1991 ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports. ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education, The George Washington University.

- Cohen, S.A. (1987). Instructional alignment: Searching for a magic bullet. Educational Researcher, 16(8), 16-20.

- Duffy, T. M., & Jonassen, D. H. (2013). Constructivism and the technology of instruction: A conversation. Routledge.

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

- Jonassen, D. H. (1991). Objectivism versus constructivism: Do we need a new philosophical paradigm? Educational technology research and development, 39(3), 5-14.

- Wright, G. (2011). Student-Centered Learning in Higher Education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 23(1), 92-97.