Geet George crossed the Atlantic, making his way through tropical rain clouds as he went. Hoping to witness their formation, he analysed the data collected by the drones he sent up into kilometres-thick layers of cloud. “It is still important to be in the field and experience the processes we have been trying to simulate on our computers for years.”

A bright orange balloon pops up over the tumultuous ocean waves, four long white arms floating just beneath the surface. “I was so relieved,” says Geet George, Assistant Professor at Geoscience and Remote Sensing. The arms belonged to one of the drones he sent up to monitor a high rain cloud from the upper deck of research vessel Meteor. “We lost contact and the drone crashed, right in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.” Fortunately, the drone’s inbuilt safety buoy was activated as soon as it hit seawater. One of their other three drones wasn’t as lucky a few days ago.

Photo by: Rob Mackenzie

Atmospheric circulation

When the drone plummeted, George had been at sea for two weeks, on his way from Cape Verde to Barbados as part of an international group of scientists. The route has been carefully plotted taking them close to the equator where warm air rises to form thick tropical rain clouds. Once the air has risen, it moves away from the equator and descends again. Finally, the air travels near the earth’s surface back to the equator. That is why the area the team are navigating is called the inter-tropical convergence zone (ITCZ). George is keen to understand the complex circulation that is set in motion here.

You encounter doldrums, areas where there is hardly any wind at all.

The area plays an important role in climate development. The changes in the ITCZ are the biggest unknowns in climate modelling. They vary from stormy conditions and rain clouds to extreme calm. “Fascinating,” George says. “You encounter doldrums, areas where there is hardly any wind at all, where sailors used to be trapped for days.” Then there are the towering clouds that bring intense rainfall. George is studying the movement of the wind, preferably per ‘cloud storey’. “We were given the unique opportunity to both measure the calm doldrums and the tumultuous big rain clouds.

With his own eyes

As a child in his native India, George loved the rain, splashing in the puddles after a good downpour, the monsoon heralding a welcome reprieve from the intense summer heat. Later he became intrigued by the clouds that produced all that rain and made them the object of his studies. George has lost nothing of his original fascination and ability to observe.

The Von Humboldts and Darwins of that time went into the field and observed with their own eyes.

“Models are great tools to describe processes taking place in the atmosphere but we also have to look at them in nature. Like back in the days, when the Von Humboldts and Darwins of that time went into the field and observed with their own eyes. While they had only their eyes to depend on we have advanced instruments which allow us to look beyond what we can see.”

George’s additional data, from satellites, aeroplanes and innovations such as sensor-equipped drones which can fly through the clouds, gives him a clearer picture of the atmospheric processes and will help improve the models predicting climate change. But however useful the models, he remains an advocate of the kind of observational research carried out on the Meteor. “It is still important to be in the field and experience the processes we have been trying to simulate on our computers for years. Only then you can put simulations and predictions in their proper context. There is no substitute for that.

Joining the expedition

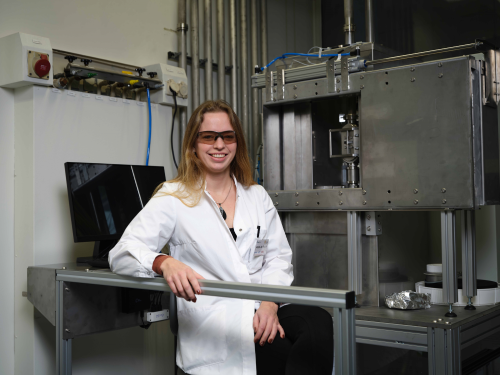

When George arrives in Cape Verde in August of 2024 to join the team on the Meteor it turns out that some 400 kilos of equipment necessary to make the measurements are stuck in transit. On arrival, the batteries of the drones are as dead as the proverbial dodo. George hadn’t expected a flying start but this is a great disappointment. Fortunately, his colleague and technical whizz Rob Mackenzie manages to bring the batteries back to life with the tools available on board. “Rob is a saviour”, recalls George. The drones are ready for take-off!

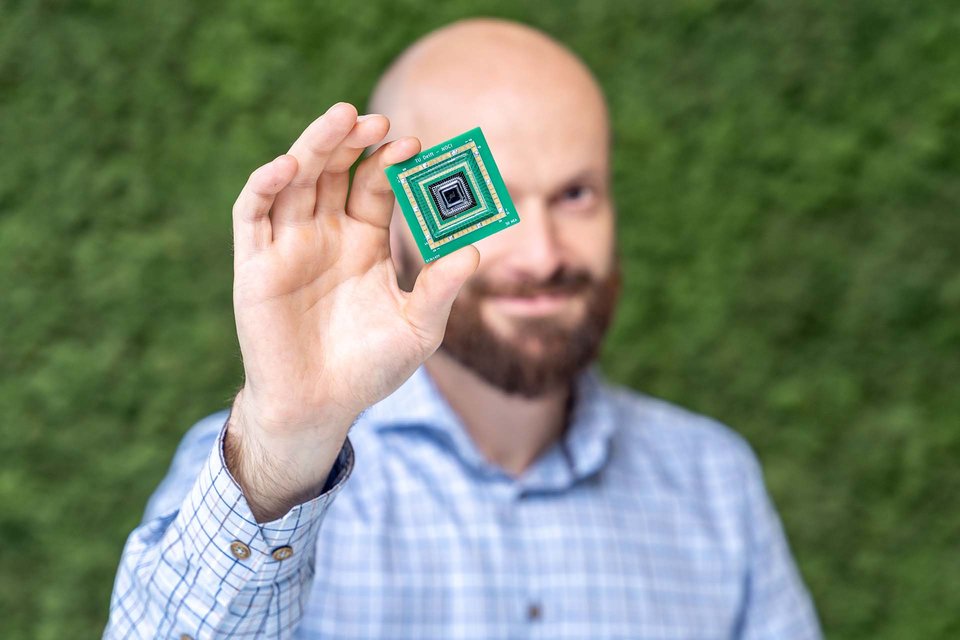

Deep clouds can reach heights of 16 kilometres and cover the entire troposphere. Three drones fly simultaneously in a hexagon pattern with a distance of as much as 500 metres between each vertex of the hexagon. They collect data at three different altitudes. Both the vertical and horizontal measurements provide a wealth of information. The drones carry sensors which measure temperature, air humidity, and atmospheric pressure. A small black box with a sensor sits high on top of each drone. “It measures wind speed,” George explains. “To do this accurately we had to attach an extra arm to the drones to prevent interference from the propellors.”

Photo by: Philipp Henning

The silence before the storm

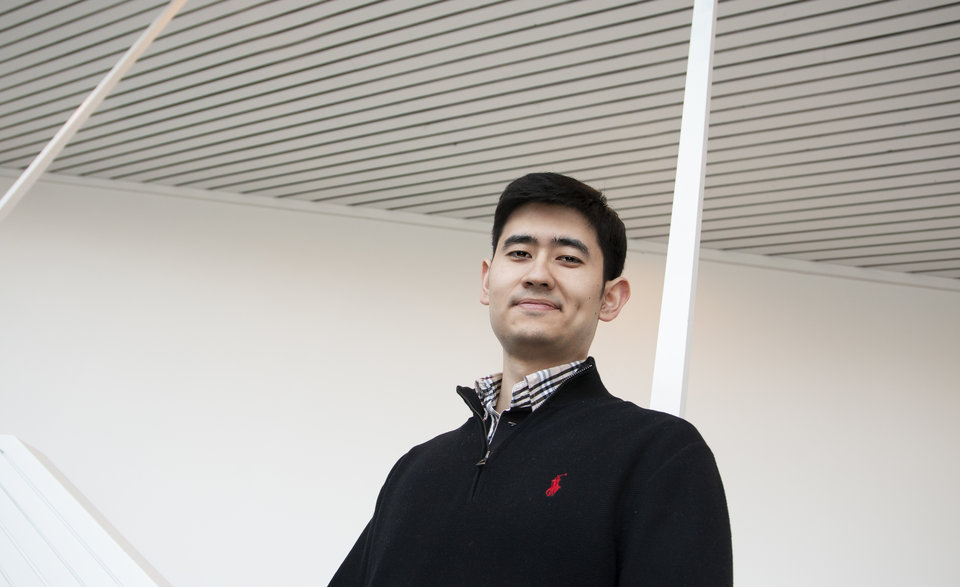

George and his colleagues see their opportunity as a storm heads straight for the Meteor. “The crew was kind of done with the tropical rain storms and would rather sail around it. But we kept insisting the skipper not to change course,” he laughs. Owen O’Driscoll, PhD candidate at Geoscience and Remote Sensing, immediately prepares the drone for take-off and is taking measurements before the storm even hits the ship. To experience ‘the calm before the storm’ is truly bizarre, George recalls. The data show wind speeds of just one metre per second. Not much later the storm breaks and the ship is buoyed by the waves. The circumstances are challenging but up goes the drone again to do successful battle with the elements. The data pours in at a rate of knots, among the enthusiastic applause of the team. The black boxes are registering wind speeds of up to eight metres per second. O’Driscoll, a drone flying novice until a few weeks ago, has turned into a real pro. “He’s a natural,” George says, well-pleased.

The drone zig-zags towards the ship and hits the deck with a gentle thud. The team members cheer and grin from ear to ear. The whole operation lasted less than 40 minutes. “To be able to gather data navigating drones in these circumstances in the middle of the ocean is a real confidence booster,” George says. “It has opened up a way of investigating the atmosphere and the clouds that hasn’t been possible till now.”

Owen O’Driscoll and Rob Mackenzie assemble the drones (left) and are happy after the drone returns back from the storm (right).

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/News/2024/03_March/CiTG/ijsberg.png)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/_processed_/6/1/csm_STORY%20BOVEN%20IMG_20220622_122856_HDR_99863128f3.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/_processed_/9/4/csm_Header%20Kshitiz%20Gautam_3f680604a0.jpg)