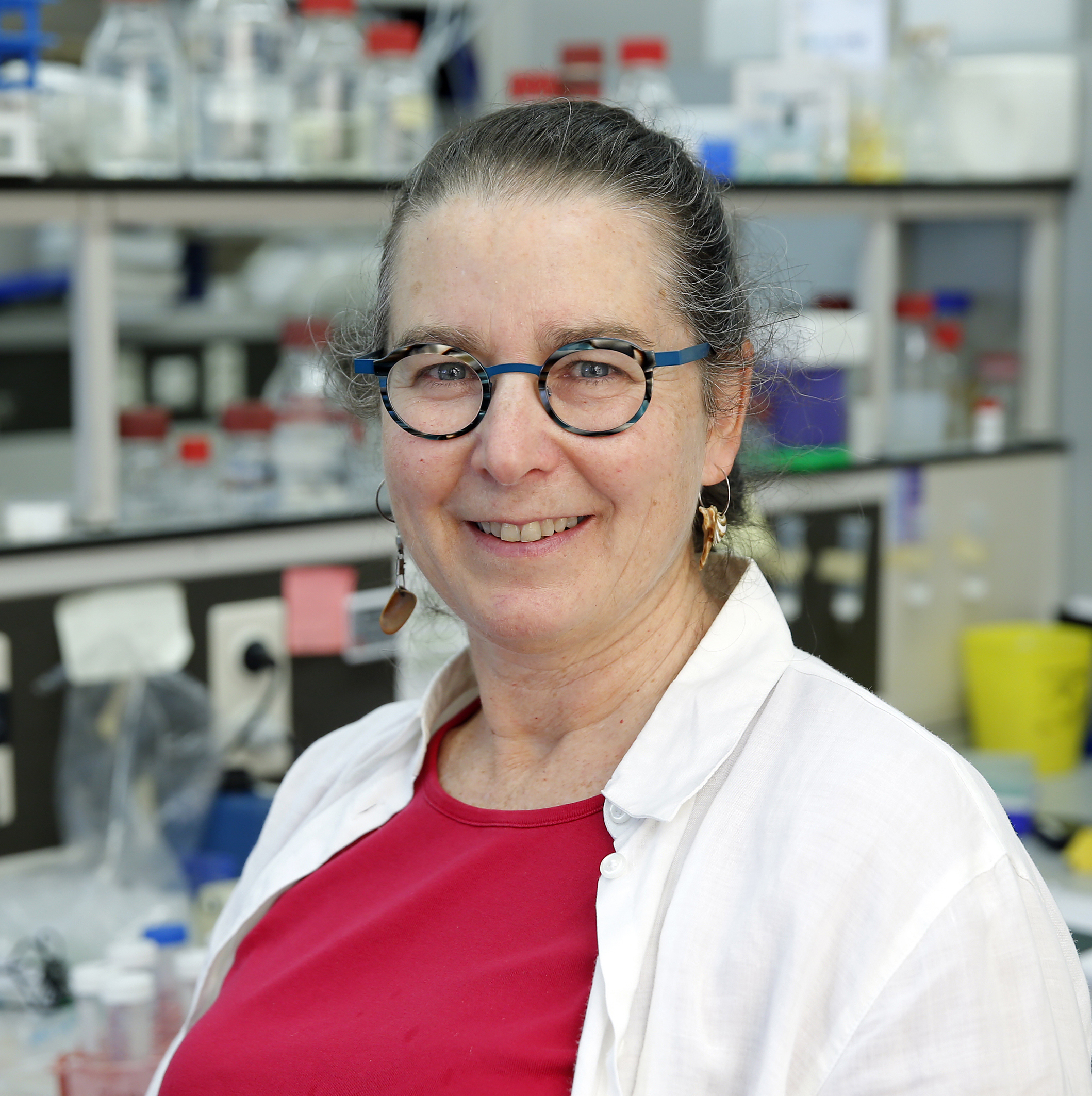

When labs at TU Delft and the Erasmus Medical Centre closed down on that faithful day in March, many of the 60 students in the joint Nanobiology programme were locked out of their final Bachelor’s projects. Programme Director Professor Claire Wyman had to come up with a solution. Enter the Corona Research Super Project.

Update March 2022

Prof.dr. Claire Wyman passed away on Thursday 10 March 2022. Claire was Professor of Molecular Radiobiology at the Departments of Radiotherapy and Molecular Genetics at Erasmus MC, Medical Delta Professor and Program Director of Nanobiology at TU Delft and Erasmus MC. Claire was an affiliated professor Bionanoscience at TU Delft. Claire’s work highlights the importance of fundamental research to produce new knowledge needed to address challenges in medical care.

It is supposed to be the crowning event of the Nanobiology Bachelor’s Programme: a semester-long project where students can showcase their abilities. ‘This year, we had around 60 students taking part. Typically, they do this in labs in Rotterdam and Delft, and most of them had just started in February’, recalls Professor Claire Wyman, programme director of the joint Nanobiology programme of TU Delft and Erasmus MC. Then, lab research was shut down and education was moved online from one day to the next. ‘At the Erasmus Medical Centre everyone was given just a few days to wrap up things before being sent home. On the floor where I have my research group, quite a few students from the Nanobiology programme had just started. I was there when some of them were told by their supervisors that their projects were stopped and they were being sent home. It was really heart-breaking to see.’

A fascinating event

‘As programme director, I had to figure out how these students were to continue with as little study delay as possible. Not all students were affected. Our programme is heavily rooted in maths and physics, so the students who were undertaking more theoretical projects could continue without physical access to the labs, but the majority had opted to do actual experimental work and they needed an alternative.’ While the situation frustrated Wyman on one level, on another level she was captivated. ‘As a scientist in health-related fundamental research, I found the corona pandemic a fascinating event. Here you had this new virus with people responding to it in ways medical science didn’t understand. The molecular details were being described in an extremely rapid pace. And all of this interesting information was being published, but I had no time to look at it, as I was too busy reorganising education.’

I was there when some of the students were told by their supervisors that their projects were stopped and they were being sent home. It was really heart-breaking to see.

Could a virtue be made out of necessity? ‘During the Bachelor’s programme our students had gained knowledge that put them in a really good position to understand a lot of the research that was coming out on the coronavirus. With the programme covering nanobiology, maths and physics, mathematical modelling, biophysics, and molecular biology, they had the skills to analyse different aspects of the pandemic. So, in discussion with the team, we came up with the plan to propose to our students that they would do literature or theory-based projects on the developing health crisis. These would be open-ended group projects, where students are given a challenge to solve, but are not told what to do.’

Meet the team

‘While it was originally my idea, I was very busy getting my own course online and helping others with their courses. So programme coordinator Johanna Colgrove got to work with Ines Chaves, who was already involved in organising student projects. They were joined by Julie Nonnekens, a Faculty member at Erasmus MC, who had offered to help. The three of them really made it happen. They devised a framework based on my experience teaching an open-ended group project course, and the literature on it, and of course their own experience. They proposed that the groups would each address a challenge involving subjects like vaccine development, disease modelling or the development of therapeutics. They also recruited people with expertise in these specific areas to help.’

Course credits and other rewards

‘We submitted a formal description to the Nanobiology Board of Examiners. It was approved for partial credit for a Bachelor end project, as not enough time would be spend on it for the full 20 credits of a regular final project. We also contacted a couple of other programmes to tell them about the project. In the end, students from vastly different programmes joined: Life Sciences & Technology, the Honours Programme of the Erasmus MC medical curriculum, the regular medical curriculum, physics, industrial design, architecture. The Medicine Honours Programme also approved this for their programme. We had PhD students acting as supervisor simply because they were interested. So while different participants got different kinds of reward out of it, all were hugely enthusiastic. It was a way of replacing a potential setback with actually being able to do something relevant.’

‘The students defined their own research questions. They met online as a group and had meetings with their supervisor. They also took part in collective Zoom meetings with other groups. Each group formalized their work in a report. For example, one group wrote a review article of the drugs that were being used at the time. Another group described tools to change behaviour. They proposed an app to motivate people to adhere to social distancing measures. A third group came up with a different kind of mathematical model for virus spread, taking into account more parameters than existing models. They are in the process of publishing this as a peer-reviewed article. Yet another group turned their attention to testing. They researched what was currently being used, and looked at similar tests and alternatives. They applied their knowledge of molecular biology to see how those tests worked and defined their advantages and disadvantages in terms of speed, cost, and ease of application.’

Real-time PCR testing is most commonly used in the Netherlands. It tests for nucleic acids, the genetic material of the virus, but this kind of testing is time-consuming and takes special equipment, so that it cannot be carried out at the point of care. An alternative is iso-thermal LAMP testing, which doesn’t require a large laboratory setup, making it quick and easy for testing on the spot. ‘Interestingly, our students also came up with this LAMP test as the best alternative before it was widely implemeted, so they came to the same conclusion that has been drawn by others as well.’ The CRSP project also resulted in a paper on the educational aspects.

Watermark

During this time, Wyman was busy teaching too. ‘I was fortunate in that it was a subject I had already taught for several years, a course for first year students on how to read research articles. Because of the ongoing crisis, I had decided a few weeks earlier that we would discuss articles on the SARS virus. TU Delft quickly provided a lot of tools for communicating with students online, and support on how to use them, so it went surprisingly well. I could reuse earlier videos with instructions, but the specific discussions on the papers I had to record anew. I found a tool I liked for recording lectures, and I used the free version that lasted as long as my course did. That meant all of my videos had a watermark diagonally across it that I had to dodge, but I think the students appreciated the humour of it.’

Presenting online is a skill we also have to develop these days

‘As I could not walk around the room and talk with each group, I had to recruit extra Teaching Assistants that could guide them through the course in a structured way. I would meet up with every group online every other week. I would then ask them how they were doing, not so much in my course, but studying on line and so on. They really appreciated that. Some of them, the more introverted ones, actually prefer working online, while others who are more socially engaged, were rather unhappy. On the whole, the course ran pretty well. Final presentation were also online, which is not the same as doing it in person. However, as I pointed out to my students, presenting online is a skill we also have to develop these days.’

Coping as best you can

All in all, the past months has been very busy for Wyman and her husband, both working from home. ‘At the time, my daughter was still living at home and working in the food service industry, which was closed. At some point, we asked her: can you please cook for us? It helped us manage to survive when she started shopping and cooking for us. We simply didn’t have the time.’

Meanwhile the students involved in the Corona Research Super Project were coping well. ‘They had chosen to do and learn something that they felt was relevant. Not everyone thrived in the situation, but in general they had a new challenge and were meeting new people online. An important aspect was that all groups had someone that kept it going, sometimes the PhD student supervising, and sometimes a very enthusiastic student. We didn’t organise that, but it helped a lot.’

The Corona Research Super Project finished with a public online symposium where all the groups presented their findings. ‘It was a big success. But it won’t end here. This is the kind of education that students have been asking for for years: working in interdisciplinary projects on important problems. At Erasmus, we are now trying to implement this formally as an optional activity for Nanobiology, clinical technology and medical students. We have also asked for funds to set this up as minor or part of an internship project for all students at TU Delft and Erasmus. We’re hoping to formalize this as an element of our educational palette.’