From landscape architect in Iran to postdoctoral researcher at the Urbanism department: Dr. Maryam Naghibi made a radical career transition. She currently studies public perception on so-called sponge city measures, mainly ‘green and blue’ features like parks and waterways. “There are many possible design choices to make a neighbourhood more resilient. But if these changes are not appreciated by locals, they are not used or maintained. That’s what I want to prevent.”

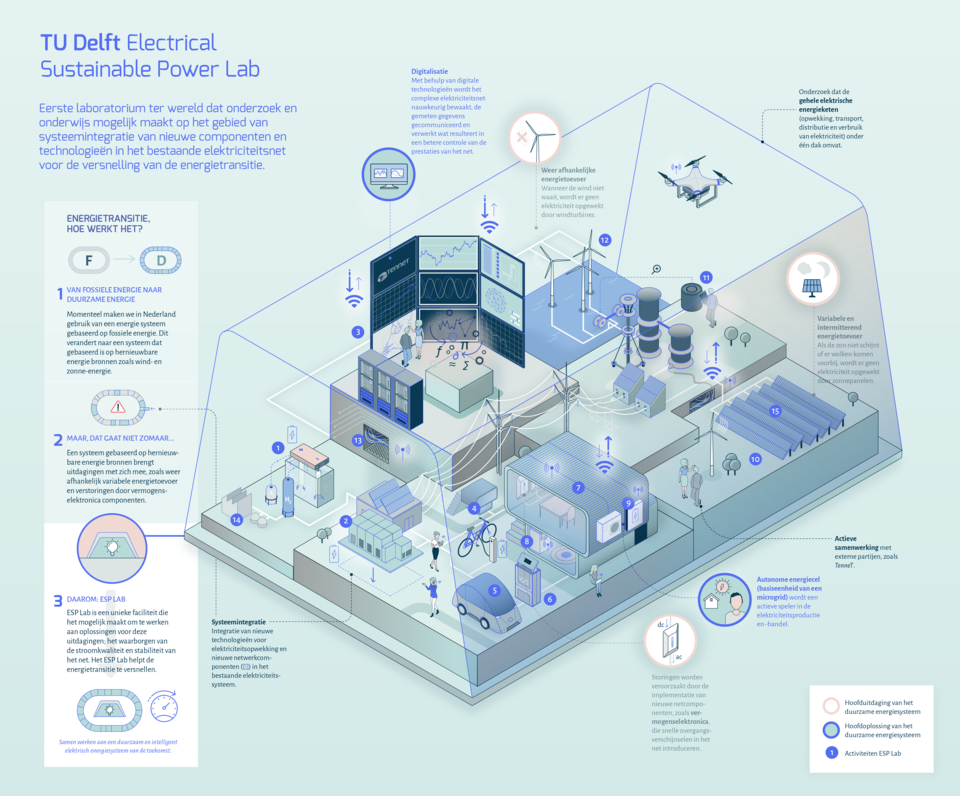

Sponge cities are green- and water-rich urban areas which can handle excessive water without flooding. With its copious amounts of rain and river water, Rotterdam is a prime candidate for ‘spongification’. Potential measures range from individual, like installing a green roof, to collective, like building a new sewer system; simple, like removing part of the pavement (the ‘NK Tegelwippen’ initiative), or complex, like digging a new waterway. Maryam studies how to incorporate residents’ needs in the spongification process. She and her team catalogue measures, determine their applicability to Rotterdam, and discuss them with inhabitants.

A landscape lover in Tehran

Maryam grew up in Iran, in a house with a small garden. There she would happily play with soil and plants, befriending cats and studying the garden’s ant colony. Every few months her mother would take her to the Tehran Zoo. Her interest in nature showed during her bachelor's degree in Architecture, where her teachers noticed that Maryam would spend much of her time and energy designing the region surrounding her architectural designs. “I wanted to provide pathways for nature to traverse the area and reach my design.” Unfortunately, landscape architecture was not recognized by the University as a separated field.

Even as an architecture student, I wanted nature to traverse the study area and reach my designs

Maryam started working for architecture firms during her bachelor, when she was only 19, and ramped up this work after finishing her degree. But a former teacher convinced her to get a master’s degree. For her thesis she was finally allowed to study landscapes. Specifically, the river valleys in Tehran. Apparently emboldened, Maryam then applied for a PhD to study and redesign ‘leftover spaces’, such as undeveloped corners on city streets. But at that moment, the Covid pandemic struck.

How to become an expert on the needs of elderly

Public life ground to a halt, and urban development with it. Maryam had to shift gears. She started to simply walk around and observe. She noticed that almost all visitors to the spaces were elderly. This observation sparked a question: “I lived in the same building as my grandmother for most of my life. I often found her looking out the window to the world beyond, longing to see more but at the same time afraid to go outside. Why?” Maryam started interviewing the elderly residents of Tehran and sending out questionnaires. What started as a pilot test, forced by circumstances, turned into a full-scale project and eventually a publication.

Now, Maryam is taking the lessons learned and expertise developed during this surprising PhD and applying all to a new setting: the delta city of Rotterdam. The challenges are vastly different, but the goal remains the same. “Elderly residents should feel safe and welcome in the city, even when the urban landscape is drastically altered to handle the changing climate and rising water levels.” Maryam collaborates with Claudiu Forgaci and their team to explore sponge city measures with inhabitants. Their methods range from relatively low-tech, such as coloured cards with pictures, to high-tech; collaborating with Stefan van der Spek of the VR Lab to let residents alter a digitised version of their neighbourhood at will.

First Rotterdam, then the world

“Future neighbourhoods should promote healthy living, both physical and mental. And social research is how I attempt to align developments with this goal. Covid made us painfully aware of the importance of good common spaces: for social cohesion, for activities, for public meetings.” Maryam has a simple reason for focussing her initial efforts on the elderly: “They will form the largest demographic in future cities, meaning their opinion should guide development.” But the outcomes will have wider benefits, since she found many similarities between the needs of elderly and those of children. Examples include low steps in stairs, paths free from slipping and stumbling, colourful picture-based signs, and a general sense of safety in public areas.

Let’s turn our cities into nature-friendly and age-friendly places.

Maryam’s work in Rotterdam is partly a proof-of-concept. She is planning to promote inclusive design at a much larger scale. “First we want to expand our methodology across the Netherlands, and later to delta regions and potential sponge cities across the world. Options include the United States, Indonesia, Denmark, Australia, China… it depends on availability, and the outcomes of our current study.” And these future sites might see her explore other ways of communicating sponge city strategies. Perhaps immersive 360-degree images, or models, or guided tours. All to get a better sense of the needs and wishes of inhabitants.

This story is published in January 2024.

More information

Read more about Maryam’s PhD research and the results in her article ‘Temporary reuse in leftover spaces through the preferences of the elderly’, published in Cities.

Maryam’s current research project is titled 'The Contribution of Sponge Cities to Resilient Delta Cities: Exploring Perceptions and Preferences of the Elderly.' It is a collaboration with the team of Claudiu Forgaci, and part of the Resilient Delta initiative.