The Dutch lockdown is very gradually being lifted. Niek Mouter is researching the public’s preferences with regard to various exit scenarios. It’s a subject that has sparked a lot of interest, with as many as 18,000 people taking part in this Participatory Value Evaluation in the first two days alone.

Niek Mouter actually had no time to spare for yet another project, but he just couldn’t resist it. “I think it’s really important for my research to feed into society’s needs and, perhaps now more than ever, scientists can really make a difference through their research”, he says. This is why he joined forces with Professor Caspar Chorus in submitting a proposal to the TU Delft COVID-19 Response Fund for research into Dutch people’s preferences and considerations when it comes to the phasing out of measures taken to limit the spread of the coronavirus. Through their research, Mouter and his colleagues hope to tackle the government’s information deficit in this area. “If you look at recent opinion polls, they’re just asking questions like ‘Are you in favour or against an app?’ That’s actually of no use at all.”

Complexiteit

A Participatory Value Evaluation (PVE) works completely differently. “It enables you to do justice to the complexity of a subject and ask people what they would do if they were making policy.” The current study places participants in a game-like setting and gives them a choice of measures together with the expected consequences in terms of numbers of fatalities or impact on the economy. If, for example, you allow people whose jobs involve contact with people, such as hairdressers, to go back to work, that’s good for the economy, but the number of coronavirus infections will also start rising again. Giving people choices in this way allows them to understand the negative and positive effects of different measures.

It was Mouter himself who first came up with the idea of the PVE. For his doctorate at TU Delft, he conducted research into ‘social cost-benefits analysis’, a tool for measuring government policy. “In that system, one of the assumptions is that you can use the choices that people make as private individuals to analyse government projects. However, do people have the same preferences when it comes to their own money as they do for government funds?” Mouter wondered. The experiments he conducted suggested that they don’t. “People are willing to spend their own money to reduce travel time, for example, yet feel that government money should actually be spent on traffic safety. They believe that the individual and the government each have their own responsibilities.”

Factor 20

There turned out to be remarkable differences between what a member of the public would do and what he or she thinks the government should do. “Consumers consider even a 45-second reduction in travel time to be important and are willing to take risks to achieve it, whereas they believe that the government should not risk a human life unless 15 minutes of travel time can be saved. The difference is a factor of 20.” Despite these remarkable research results, Mouter’s ideas did not find immediate favour. “I spent a year presenting my results at all kinds of conferences and failed to convince a single person. That was until I met my colleague Paul Koster from VU Amsterdam at a conference in Chile and I managed to convince him. That evening, over a pizza, we ended up outlining the basis for the PVE method on a paper napkin.”

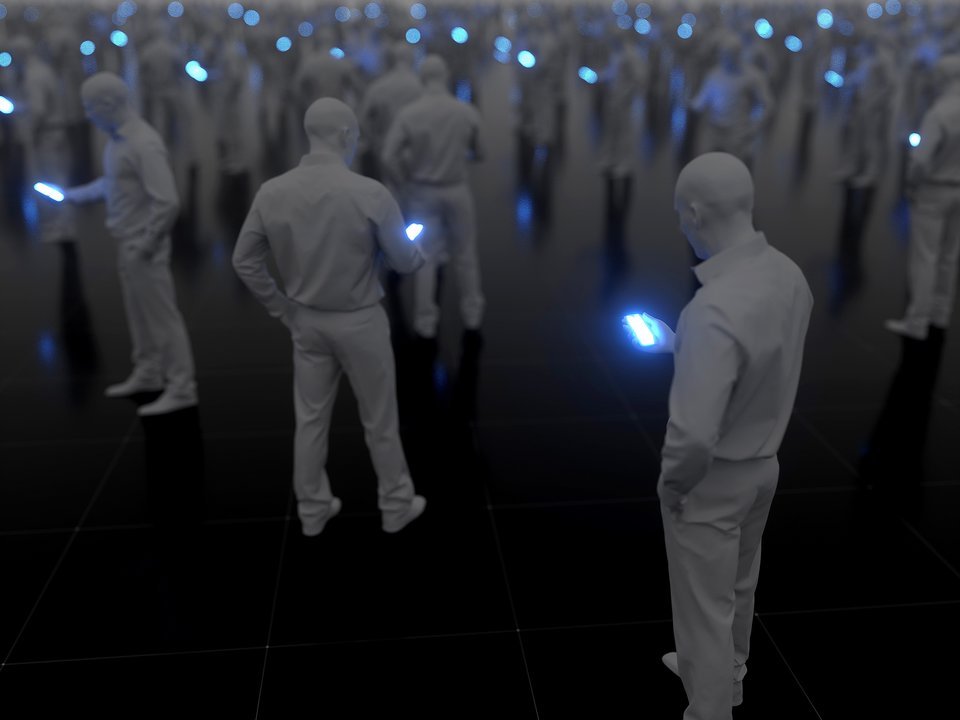

The PVE they developed is not based on people’s private choices, but instead places members of the public in the government’s position. “Government money can only be spent once. PVE participants can see the various policy choices and have to distribute collective funds based on the collective choices that they would make if they were the policymakers. In practice, the PVE not only proved effective for evaluating policy – government authorities also see it as a tool for public participation. “Public participation is currently organised in such a way that you usually only reach a few dozen older people willing to attend a meeting. We are able to reach as many as 5,000 people.” A PVE also has a third function: raising awareness. “People who take part become aware of the effects of their choices; something that they may initially think is a good idea turns out to have negative consequences. It enables you to involve them in the quandaries of decision-making.”

The current crisis has its fair share of quandaries, although not everyone may regard them that way. “There are also people who say: we need to reopen the country and get the economy moving again”, says Mouter. But who will the Cabinet end up listening to? “That’s something we also ask: the extent to which participants think that the results should be taken into account by politicians. In all of the PVEs so far, we’ve seen that people are willing to take part and be serious about giving their opinion, yet are reluctant to place too much importance on it: in general, only 15% of participants feel that the results of this kind of public consultation should be a decisive factor in political decision-making”, Mouter explains. “Having said that, there is a difference between highly-educated and lower-skilled workers. In a recent PVE we conducted for the municipality of Utrecht’s heating transition, 40% of lower-skilled participants felt that the public’s advice should carry more weight than that of experts.” This is probably related to their confidence – or lack of it – in the integrity of experts.

Feedback

In designing the study into exit scenarios, Mouter gained feedback from fellow researchers, as well as policymakers from the Ministry of Finance and the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM). “I like to involve as many stakeholders as possible in an experiment, as that often gives it more substance. Of course, I always explain why we take on board any feedback offered – or indeed don’t. From a statistical perspective, for example, there may be different interests at stake in an experiment than from a policy perspective. We want to avoid designing an experiment that may be highly relevant to policy, but at the same time is so statistically inefficient that the data become unusable.”

Beyond 20 May

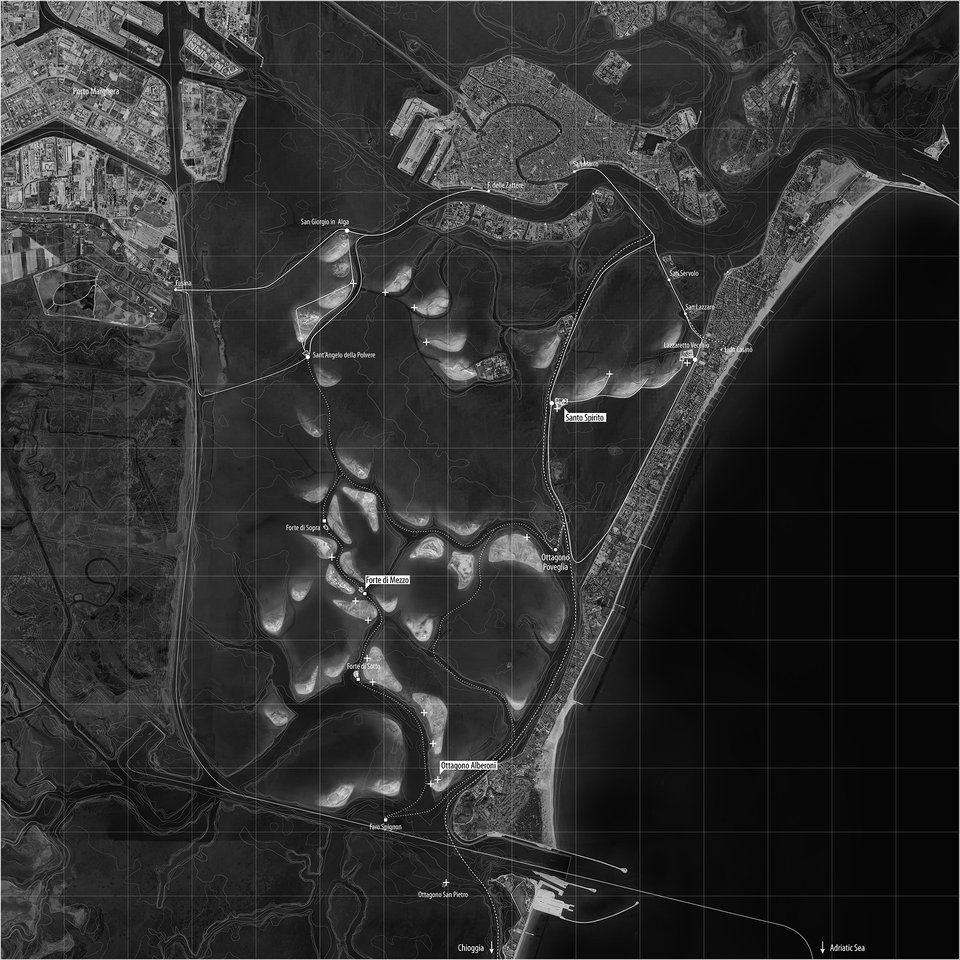

With the current study almost completed, the next is already about to start. “As soon as we know the decisions from the press conference on 20 May, we will continue with a study into the longer-term choices. Ultimately, the question is: what we do until there’s a vaccine?” he explains. “How quickly do we want the crisis to be over? You can quickly – but with a lot of fatalities – try to achieve herd immunity, or continue living in a 1.5-m society until there’s a vaccine. We could also start by bringing an end to the measures in provinces like Groningen, Friesland and Drenthe, and gradually rolling that out to other provinces. Yet all of these scenarios have their consequences.” For this study, Mouter and his colleagues are collaborating with scientists at Erasmus MC and Utrecht University, who are working on epidemiological models.

Methodologist

Mouter is glad that he is able to make this kind of direct contribution in this time of crisis. However, he stresses that, above all, he is a methodologist. “My aim is to design new methods to evaluate government policy and improve existing methods. By doing so, I want to provide policymakers with the best-possible knowledge and information, but it’s up to them whether they make use of it”, he says. This also applies in the current situation: “I think it’s important that, when making decisions, Prime Minister Rutte is aware of what preferences large groups of citizens have when it comes to the trade-offs. But he’s still at liberty to disregard them in his decision-making.”

The fact that the theme is so relevant is hugely important to Mouter. “I’ve done research with the RIVM on cutbacks in healthcare and on the energy transition in Friesland. These are all major themes that I’m happy to invest my time in.” There is no doubt that these themes will continue to play a role in his work after the crisis. For now, Mouter and his colleagues are focusing their efforts on subjects related to coronavirus. “We’ve already published the results of an initial experiment in a Dutch-language paper. It took two weeks from the funding being awarded to the publication of the report outlining key findings – a process that normally takes at least four months”, he explains. “Everyone is showing a remarkable willingness to be flexible and work until late at night or at weekends. Our team was already full of enthusiastic people keen to develop the PVE, but now there’s even more drive and sense of unity. It’s great to be part of that.”