What can planetary science on the bone dry Mars teach us? What happened to its atmosphere? And, are there possible fall-back options for humankind on Earth? We spoke with Sebastiaan de Vet, planetary scientist at TU Delft.

“If we look at planets and see how on planetary scale climate changes over sustained periods of time, we should be getting a feeling of urgency for the climate problems on Earth. The influence that humankind has had on the atmosphere and the climate has been indisputably proven. I understand why the ‘Elon Musk generation’ still believes in it, but Mars as an extension of Earth will not become a reality. There is no planet B and Mars is proven to be not a back-up option.”

Interesting. Yet, also slightly terrifying. What should we do?

“We should at the very least not put our trust in a technological breakthrough and hope that we can divert to another planet. We simply do not have time for that. We should focus on climate adaptation and mitigation.”

Let’s talk more about that later. But first, where does your fascination for space come from?

“I have always been curious, especially when it comes to stargazing. I remember well that when I was fifteen years old, I bought my first telescope from the money I earned from my newspaper route. On a cold December night, I put up the telescope out of the window in my parents’ home, aiming it at Saturnus. Wow, what an extraordinary experience! Watching with my own telescope to a point in the sky. I saw a planet with rings around it, a completely different world at a billion kilometres away. Looking at Saturnus was literally an eyeopener.”

We need to realise that in our solar system, this ball on which we live is an extraordinary place.

Where did this experience bring you?

“The years after, I saw more and more of the sky; Mercury, Venus, and Jupiter. This is what I wanted to keep doing. The path I would follow started to become clear, slowly but steadily. I became a member of the public observatory, in order to share my story and experiences with other people. My interest in planets kept on growing and, via a small detour, I eventually ended up studying Earth Sciences.”

And what about now?

“Currently, I research places on Earth and in our solar system. I mainly focus on the ‘rocky side’ of the solar system. The story of rocks and landscapes. One of the stories I study is that of Mars. Very interesting, because in this way we can learn how this planet has changed. We try and capture how the planet has evolved and see what changes took place. We research the geosciences of the solar system, such that we can understand better the story of planets and planet formation.”

What can we learn from those landscapes?

“A lot! We look at how the landscape here on Earth evolves and what the relationship is with climate change or, for instance, weather patterns. What the influence of humans is on that landscape. We can also look from a geological perspective to planets. That can also teach us a lot about climate and climate change. Take for example the surface of Mars. A landscape that has been evolving for billions of years. Beautiful stories have been written in the rock formations of planets.”

Which planets are for us most interesting?

“Within our solar system, we have 4 rocky planets; Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. We study the evolution of these celestial bodies. What the similarities and differences are. Venus is completely different, but Mars is more Earth-like. Mars also has climate change, ice ages, and volcanoes. There have been lakes, rivers, and possibly oceans. Thanks to almost sixty years of planetary science and missions to Mars, we have come to learn much of the geological history of the Red planet. Once Mars was a much more pleasant place. Now, it has become a bone dry dessert planet, with a thin atmosphere and no sign of life.”

Looking at Saturnus was literally an eyeopener.

What happened?

“Long ago, Mars had a magnetic field. Something happened inside its core – we don’t know what – what caused the magnetic field to disappear. This had big consequences for the atmosphere of Mars. Because of the influence of solar winds – a stream of charged particles coming from the sun – the atmosphere slowly dissipated into space. This meant that the air pressure on Mars became so low that water started boiling away, even at Mars’ normal surface temperatures. This changed the climate on Mars completely and made the planet uninhabitable.”

Is that what makes Mars so important for research?

“The fact that planetary scientists are so interested in the early years on Mars, has a good reason. Mars was still wet. There was water, rivers flowed, and the climate was better. This was around the same time when life on Earth started to form. Mars was not so different from Earth back then. That period, over 3.5 billion years ago, is very interesting. That was the turning point, after which Mars has become more and more uninhabitable. Mars has physically evolved different from Earth. We know this because of planet research and all our observations. The story of Mars is rich and very valuable for us.”

But what does this mean for Earth?

“When we look at the geological history of Earth, we see that there have been long lasting variations in climate and for example also CO2-concentration. There have been large fluctuations in the past, but the time factor was different back then. Right now, we can see changes in human scale, which makes the climate changes right now much more urgent and complex. We need to realise that in our solar system, this ball on which we live is an extraordinary place. The circumstances here are unique. We should handle that with caution, in a sustainable way. Because of the actions of humankind, we are reaching and even going beyond the limits. We have a lot of information on planet Earth. The planet science perspective gives a feeling of urgency when you look from that perspective to the current climate problems on Earth. That motivates to handle even more adequate on the current challenges.”

What could you and your team add and develop to do this?

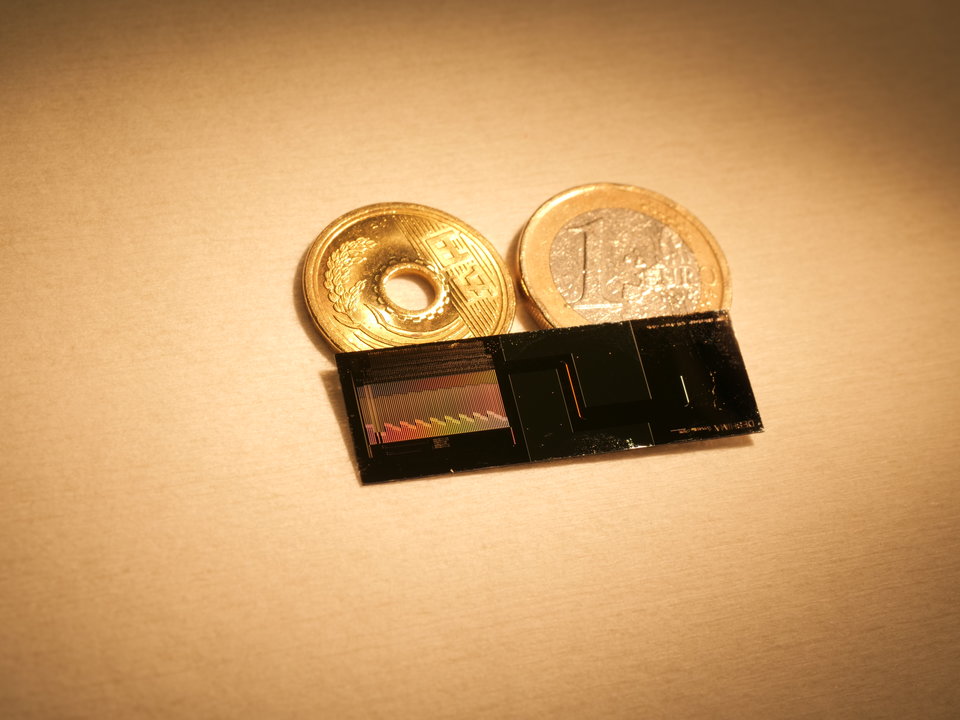

“Landscapes are an extraordinary source of information to use to determine the formation of a celestial body. It isn’t limited to Mars only. This is possible for Mercury, Venus, or for instance icy moons. Some places in our solar system, like those icy moons, also have the possibility to sustain life. The only problem is, is that they are farther away and satellites visit them less frequently. This makes their story harder to tell. Furthermore, it would be good to expand our ‘toolkit’ and read those scenic stories with new technology. We could for instance make use of smart drones, lab experiments, and numerical models. This is what we are focussing on within our research group. We have colleagues working on the ‘inside’ of planets, the structure of planets. We are also looking at the surface, the place where the chemistry happens. The place where the internal processes and atmospheric effects come together and create a climate where landscaping processes and interaction takes place. If we are able to research the interaction between the internal and external of a planet with new techniques and instruments, our landscape stories will be richer and more complete.”