A worldwide sun awning

Last August saw unprecedented high temperatures in the Netherlands and across Europe. There was also more advertising for sun awnings and roller blinds than ever before. Climate professor Herman Russchenberg is now calling for a worldwide sun awning.

It was the first time the Netherlands ever recorded eight consecutive days of tropical temperatures. Temperature records are being broken so quickly that it has become normal. Is no one concerned by these signs of the strength of climate change?

Of course they are. Researchers are seeing numerous countries failing to realise their self-imposed climate targets. Energy consumption remains high and the extra capacity from renewable solar and wind energy will easily be outpaced by the increased use of data centres, air conditioning, electric cars and green hydrogen production. This is compounded by the fact that all of the self-imposed CO2 reductions together are insufficient to remain within the critical boundary of 2 degrees of temperature rise (compared to the pre-industrial age) in the Paris climate agreement. “Clearly, the actions we’re now taking to reduce CO2 emissions are not enough”, Professor of Atmospheric Remote Sensing Herman Russchenberg said recently in NRC. “It will get too hot on Earth. That’s why, by 2040, we need to have the technology ready to cool things down temporarily.”

Changing the climate

Little surprise then that climate researchers are looking for new technology, and in doing so beginning to encroach on an area previously regarded as taboo: Climate engineering, or in other words: deliberately influencing the climate. Until now, climate change has been an unintended side-effect of the carefree consumption of fossil fuels and the greenhouse effect of the CO2 released in the process. Deliberately influencing the climate soon summons up images of a sorcerer’s apprentice whose naïve interventions end up making things worse.

Bogeyman

Prof. Herman Russchenberg, Director of the Delft Climate Institute, is only too familiar with the issue. He’s long been considering how you can influence the climate, and going public on this. “I used to be dismissed as a bogeyman, a professor in a white coat doing crazy things and wanting to ruin the Earth.” He’s recently noticed much less aversion and an increase in interest. “The idea that climate change exists is really starting to sink in. People are realising that we need these kinds of technologies and that we need to prepare ourselves.”

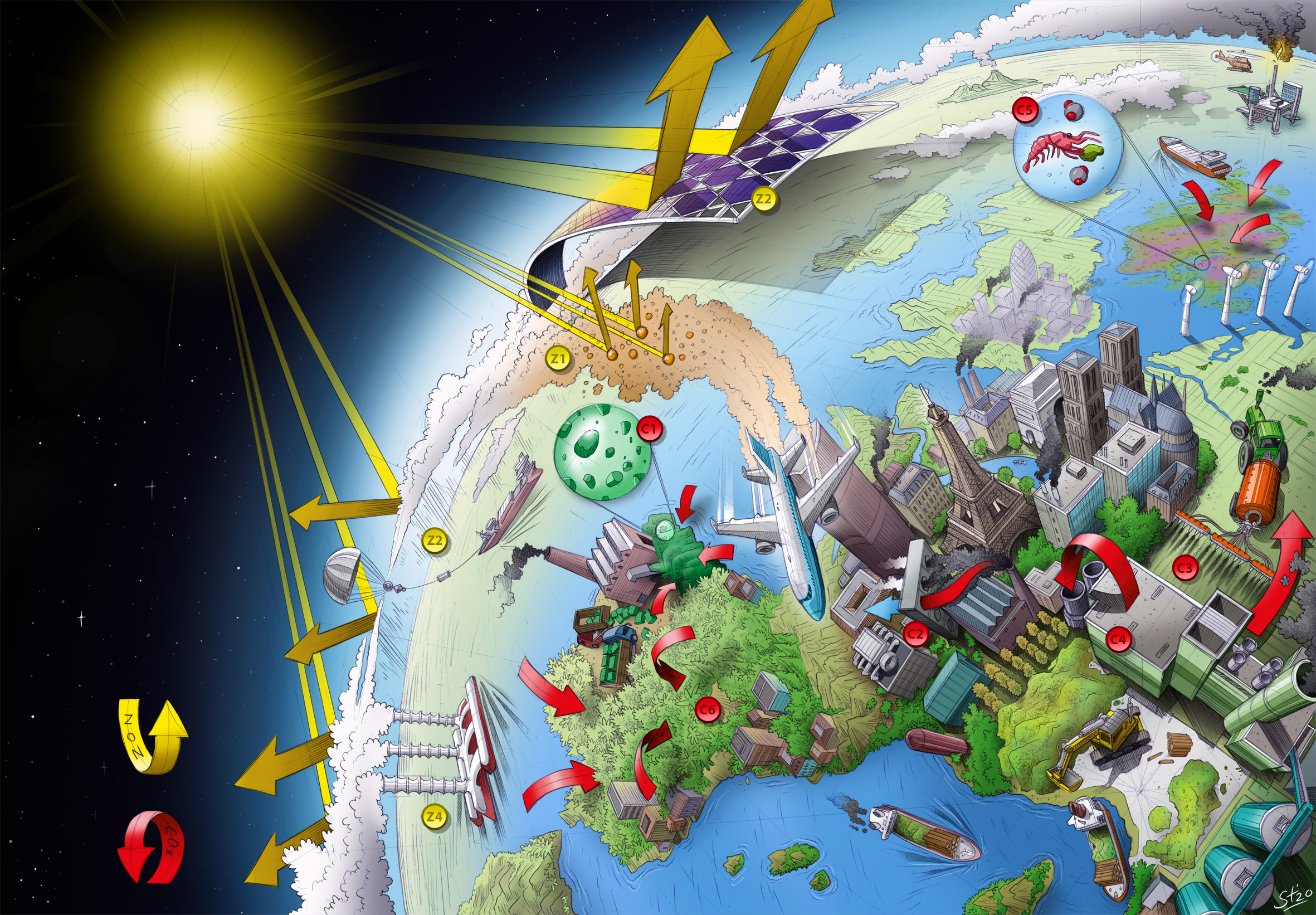

The technologies that Russchenberg is referring to can be divided into two categories: reduction of solar radiation (see the drawing on page10, Z1 to4) and CO2 removal (C1 to 6). The field of geo-engineering, or climate engineering as Russchenberg prefers to call it, now has 10 different technologies in the very early stages of research.

Of these, stratospheric aerosol injection (SIA) is considered to be the most promising, both in terms of technology and financial feasibility.

Studies from Harvard envisage 4,000 flights per year with a special tanker aircraft at an altitude of 20 km, spreading small white sulphate particles into the stratosphere. The fact that particles like this can effectively reflect back part of the sunlight, reducing the solar heat that reaches the earth, is known from major volcanic eruptions that tend to be followed by temporary but worldwide cooling.

Popular

The first exploratory research is already being conducted in Delft. This includes the design of the stratospheric aerosol geo-engineering aircraft (SAGA). In laboratories, students are measuring the reflections of droplets while others are modelling cloud formation and the effect on climate models.

Russchenberg sees that climate engineering is popular with students. It gives the sense that something can be done about climate change. “The approach is more positive than the way political policy is often seen, that you have to sacrifice something.”

Yet countless technical, practical and ethical questions remain. What will be the effect on global precipitation, for example? How will the aerosols affect the ozone layer? Who will decide when and how many aerosols can be sprayed and how sure are we of the effect? Could we go too far, and, if so, what then? What happens if we suddenly stop doing it after a few years? And the most dangerous of all: how do you stop people seeing climate engineering as an excuse for no longer reducing their CO2 emissions?

Russchenberg is aware of all these uncertainties, but still hopes that the Netherlands and Europe will invest in the research, if only in order to be able to engage in high-level discussions with the United States. “They’re pumping millions into this research and acquiring a lot of knowledge. In my view, climate engineering is too important to leave to a single country. These are technologies with a global impact and you don't want to leave decision-making in the hands of a single country.”