‘It’s time to call it a day’

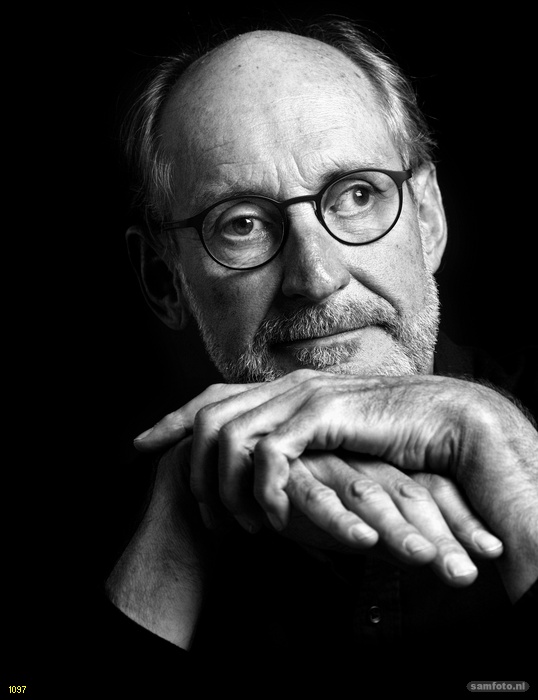

Why does the Netherlands excel at water management? It is not because of the polders, but because of centuries of work by Dutch engineers all over the globe. Time for a retrospective with departing hydrologist Huub Savenije.

The Professor of Hydrology (Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences) took his leave from TU Delft on 28 September. The day before was spent with 20 of the 35 PhD candidates he supervised over the years. They have flown over especially from Africa, Asia and South America. It is a fitting farewell for a man who’s field of research has always been outside the Netherlands. ‘The hydrology of the Netherlands is actually not very interesting,’ he thinks. ‘As Louis XIV remarked: the Netherlands is made of deposits from the French rivers. And it’s true! But the French rivers them-selves are much more interesting, as are the higher stretches of the Rhine.’

Your farewell speech, ‘Did everything fall somewhere else?’ sounds like a reference to your inaugural address in 2005: ‘Most falls somewhere else’. What is your message?

“I used the falling somewhere else as a metaphor for the problem with hydrology. We conduct microscale measurements and are supposed to explain them at the macro scale. But it’s also a metaphor for research that often goes wrong. I mean to say: not every shot hits its target. In fact, I am convinced that you need to miss your target many times before you can hit it.”

How does missing your target help you to hit it?

“I believe you only get breakthroughs if you go off the beaten track. Of course you can stay on that track – together with all the competition – because everybody does that. Breakthroughs are only found on unbeaten paths, but sometimes the paths are dead ends.”

Doesn’t that contradict NWO’s research policy, that most calls to mind ‘research on de-mand’?

“That’s exactly my point. NWO (Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research) and European grant programmes expect you to submit a high-risk proposal, but the assessors subsequently question the feasibility of the idea and whether it harmonises with existing research. That forces you to stick to the beaten paths. Such research is also easier to publish. Colleagues are interested in the tiniest improvement on what we already know, especially if they are cited in the references! But if you do something new, they think: ‘What is he up to?’ Or: ‘What does he know about my field?’”

From his start in 1978, Savenije studied the penetration of salty seawater in open river mouths. These estuaries are rich ecosystems, fertile fishing grounds and key agricultural areas (as long as the salt does not infiltrate too far). Inspired by the colourful stories he heard about Africa and Asia from his former tutor, professor Adriaan Volker, the young engineer Savenije headed to Mozambique in the 1970s to study salt penetration in estuaries.

How did you go about doing your research in the estuaries of Mozambique?

“Without any literature or means of communication, I set down to puzzling it out myself. I start-ed conducting measurements. I initially thought it was all very complicated – that’s what I had learned in the lecture theatre – but in my measurements I discovered a remarkable simplicity. It was really quite easy to describe the salt penetration mathematically. It took me years, of course, but I discovered analytical equations I could use to describe salt penetration in simple terms. I went on to apply my findings in four estuaries in Mozambique. After that I worked with a consultant and travelled all over the world, and the theory worked everywhere.”

Savenije became known as an internationally active researcher with an eye for overarching patterns and international cooperation. He was awarded a PhD for his formulas for salt penetration in estuaries in 1992. But he continued to wonder how it was possible that the outcome of such complex three-dimensional flows, involving salt and water in a multi-branched pattern of cur-rents, was apparently so easy to describe with a few simple formulas. He found the key to this puzzle only a few years ago, when he started to notice a parallel between river basins, the circulatory system and the veins in a leaf: nature always finds the most efficient path.

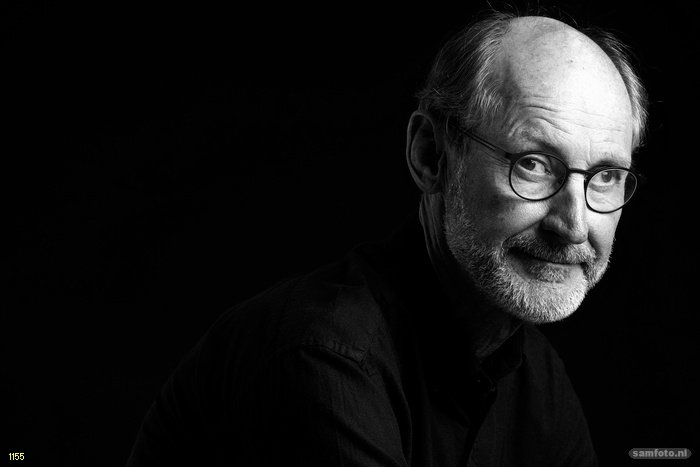

Photo © Sam Rentmeester

Can you explain more about the veined structure of river basins?

‘You see, there are two different approaches. Reductionists divide the world into little pieces and apply their balance equations to them.

Holists like me examine the behaviour of the whole system. We assume that a system is more than the sum of its parts. I discovered that a river basin forms patterns, like the veins in a leaf. When water flows through a leaf you can see a pat-tern in the veins, and the same applies to water that flows through a human body. My veins and your veins are not the same, but they display the same pattern. The pattern determines how the blood flows such that every cell in your body gets enough oxygen with every beat of your heart. Suddenly it becomes simple.”

Do you see the same pattern in hydrology?

“My observations suggest simplicity, but the basic equations show that it's complex. So how do you reconcile the two? I have thought much about this, and I think that it is related to the second law of thermodynamics (increasing entropy in an isolated system, ed.). This is a very important law that describes how everything has a direction; that we grow older, and not younger. The law also limits the efficiency of processes, because even if the energy remains constant, the entropy will increase, which means some of that energy is released as heat. When I speak of patterns, I am essentially referring to efficiency. The pattern of your veins is a very efficient way of getting oxygen to your cells. A river basin with a leaf-like vein pattern is a very efficient way of draining off water.”

Did idealism drive you to seek out far-off countries, or was it a lust for adventure?

“It was more than that. Why does the Netherlands excel at water management? It is not

because of our polders, but because Dutch engineers have always worked all over the globe. Our colonial past has brought us experience of complex and untamed systems, with cyclones, extreme downpours and raging rivers. I was taught by people like professor Adriaan Volker, who worked in the Dutch East Indies. Our fame is based on our knowledge of the world, not just the Netherlands.”

You helped to establish the TU Delft Global Initiative. Was that because of your conviction that Dutch engineers understand the world?

“Cooperating with developing countries not only serves a humanitarian goal, it’s also good for the Netherlands. Such relationships are important for us. Everybody is talking about climate change, so we need to learn from countries that already have our future climate. Our storms will become more intense. If you want to understand this, you need to go to the countries where cyclones occur regularly. The science of hydrology involves finding solutions for the problems of tomorrow by studying how systems work. The Netherlands is too small for that.”

Savenije talks quickly and passionately. He pauses to take a call from Vietnam; ‘Excuse me, I have to take this call.’

Why does the Netherlands excel at water management? It is not

because of our polders, but because Dutch engineers have always worked all over the globe

It is difficult to imagine that you will be retiring.

“Everybody says that, but it’s a fact. I have spent the last five years bringing everything together, and the last two years completing unfinished business; I’m satisfied I can leave it now. I am still supervising a few PhD students, but I’m old and no longer need to be in the vanguard. It’s time to call it a day.”

CV

Professor of hydrology Huub Savenije joined the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences in 1998 where he led the Water Resource Management research group. He graduated from TU Delft in 1977, and went on to work in Africa and Asia, returning to Delft in 1990 to complete his doctoral thesis (1992). Two years later he was appointed professor at Unesco-IHE in Delft, and in 1998 he was made a professor at TU Delft. He served as editor-in-chief of the journal Hydrology and Earth System Sciences (HESS) that became an open access resource in 2005. Last year, the American Geophysical Union (AGU) gave him the International Award for his contribution to the field and his scientific work for developing countries. Savenije has been succeeded by Dr Hessel Winsemius, formerly of Deltares.