Finding eddies and fresh water

Delft researchers are investigating how salt and nutrients are transported by ocean currents, and how submarine groundwater discharge affects coral reefs. They took part in a large research expedition across the ocean aboard the research vessel RV Pelagia, which left Texel in December last year.

How can we gain a better grasp of the changing oceans? That is the central question of this expedition, called NICO (Netherlands Initiative Changing Oceans). The RV Pelagia, the research ship of the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), sailed south to Gran Canaria, then crossed over to Curaçao and Sint Martin. It is now heading back to Europe. In total, the research team consists of about 130 scientists who joined the crew at different legs of the journey. The journey will finish at the end of July. Delft researchers joined the crew in the Caribbean in February.

Right from the start, the expedition proved not to be for the faint-hearted. With high waves and a 7 Beaufort wind force, RV Pelagia left its home port of Texel – where NIOZ is based – on 13 December, two days later than planned. The crew encountered some unexpected technical problems. One of the fuel tanks leaked and needed repair. “Nothing to worry about,” said Thomas de Greef, head of the NIOZ marine facilities. “This is a common problem with old ships like the Pelagia. The metal just gets thinner over the years.” But he did add that the ship is still seaworthy.

Diameter of over 100 kilometers

“Maybe it was a good thing that I did not board the ship myself to do the experiments,” says oceanographer Dr Caroline Katsman, laughing. Katsman, who works at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences (CEG), is an expert on whirlpools in the ocean, also called eddies, and how these large, slowly spinning vortices – with diameters that can sometimes amount to several hundreds of kilometres - affect ocean currents. She designed the measurement programme that took place when the ship sailed the Caribbean.

Katsman’s colleagues and students performed measurements along a transect that cuts right through an eddy with a diameter of over 100 km between the islands of Aruba and Sint Martin. They measured the salinity and temperature at depths of up to 5 km. This is exciting because until now, researchers have only observed eddies superficially with satellites. Eddies are interesting because they affect ocean currents at large and as such, the earth’s climate. Moreover, their higher temperatures mean that they may also fuel hurricanes.

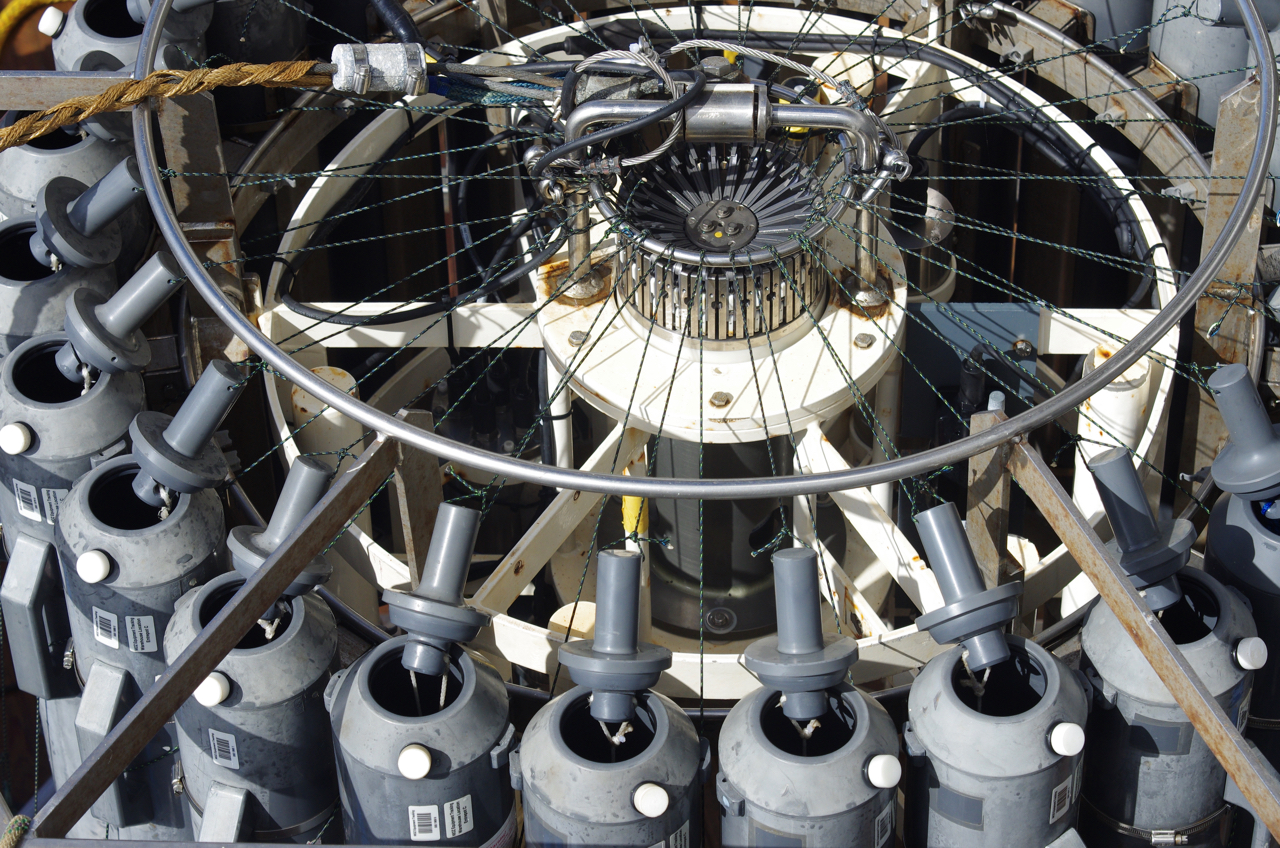

One of the most important instruments to study eddies is the CTD. CTD stands for conductivity, temperature and depth. “On the Pelagia, this instrument is mounted in the centre of a steel frame of approximately two metres square, and has twenty-four water sampling tubes, called Niskin bottles, on the outside,” oceanographer Kirstin Schulz, postdoc NIOZ Sea Research, writes in the blog of the NICO expedition.

“Each Niskin bottle contains 12 litres of water, has an opening at the top and the bottom, and lids at each end which are connected with a spring in the middle of the tube. A system of ropes and hooks keeps the spring under tension and the Niskin bottle open until a signal from the connected computer on board releases a hook, and the lids snap and close the bottle. This steel frame is lowered into the water with a winch from the ship. It takes almost an hour to reach a depth of two kilometres.

“On its way up, the Niskin bottles are released at certain depths to collect water samples. The samples are analysed for their nutrient content. The CTD is then brought back on deck, which is again an adventure – with all the bottles filled, the frame now weighs a ton. In addition to the salinity profiles (calculated from the electrical conductivity of water) and temperature, the CTD also has sensors to estimate the oxygen and chlorophyll content of the water.

The Delft team is collaborating with biologists from Wageningen University who took water samples to study plankton. Since the salinity and temperature of the water in the eddy differ from those of the surrounding water, it is believed that the fauna also differs. The researchers are also studying marine mammals, seabirds, turtles and large fish species like sharks and sunfish.

Groundwater into ocean

On the island of Curaçao, hydrologist Boris van Breukelen (CEG Faculty) hopped on board. Together with colleagues from Wageningen University and the University of Amsterdam, he is researching where and to what extent groundwater from the island flows into the ocean. Most fresh water that flows from the island into the sea seeps undetected through the ground since the island is made of very porous rock.

“We want to get a clearer picture of the hydrology of the island and the surrounding sea. The groundwater contains a lot of pollutants, like nitrates and phosphates, that cause algal growth and threaten the coral reefs,” says Van Breukelen. Among the measurements performed by the team were those on salinity and temperature in the waters surrounding the island to detect the areas where the polluted water flows into the ocean. It is a tough challenge to find the sources of fresh water in the vast ocean as the differences in temperature and salinity are very subtle.