Dinosaur skull rises from a 3D point cloud

The Triceratops skull is back in the Science Centre. The restoration combined 66 million year old bone fragments and today’s scientifically modelled 3D prints.

Skull 21 has been through a lot, especially in the last 129 years. Some 66 million years ago, Skull 21 was the head of a large dinosaur in what would later become North America. It was about nine metres long, three metres high and weighed 13 tonnes. Triceratops prorsus, as it would later be called, was a stocky muscular colossus that lived off plants and shrubs. They worked these out of the ground with their nasal horn, grinding them with a long row of small teeth that worked like a shredder.

Scholars are still divided about the role of the two upright horns and the neck shield. Were they the equivalent of a peacock’s tail, or a defence against the predatory Tyrannosaurus rex, who also wandered these grounds at the time? Either way, at one point this colossus crossed the Styx, and left his skull and bones to fossilise. Even though at some point the skull was crushed between layers of earth, many millions of years later it surfaced again. In what is now called Wyoming, USA. In 1891, with 30 others, the skull was salvaged by a team from Yale University. It was given the catalogue number YPM 1832.

Broken bones

The trip to the Netherlands was, if possible, even more wondrous. The Delft palaeontologist Professor Jan Umbgrove was aware of the extensive Yale collection in the early 1950s and he wanted to have one item as a masterpiece for the Mineralogical Museum, the visiting card of the Faculty of Mining. In exchange, he offered a part (only doubles) of the so-called Timor collection - a collection of fossil shells that tell a lot about marine life in a particular period (Perm and Triassic). TH Delft, the later Delft University of Technology, had collected them in 1910 and 1916 on the Indonesian island of Timor.

To speed up the exchange, Umbgrove had already sent the shells out, says Science Centre director Michael van der Meer. If Umbgrove wanted to put the Americans on the block by doing this, his strategy succeeded. It was a pity that Umbgrove didn’t live long enough to enjoy his success; he died in 1954 - two years before the skull he had ordered arrived in Delft.

The restored Skull 21 was put in a crate and shipped to the Netherlands in 1956. Unfortunately, the ship headed into a storm and the cargo was severely battered. Also, the delivery seems to have been less than gentle. Whatever the cause, when the curator of the Mineralogical Museum, Doctor Pieter Kruizinga, opened the crate, he saw more than a hundred pieces of debris. Kruizinga had retired five years previously, but he did what he had to do: he put the puzzle of his life together. The dinosaur skull was resurrected in his hands. For more than half a century it would be a showpiece of Delft’s mineralogical collection. It remained there until the entire collection was transferred to Naturalis in Leiden in around 2014.

Naturalis

“There were some mistakes in Doctor Kruizinga’s reconstruction,” observes preparer Martijn Guliker of the Dinolab Naturalis. “The horns were standing upright on the skull like a young god, but that’s not correct. Just like with goats, the horns first go upwards and later slant towards the front.” To reconstruct it accurately, the Dinolab staff decided they had to go back to basics.

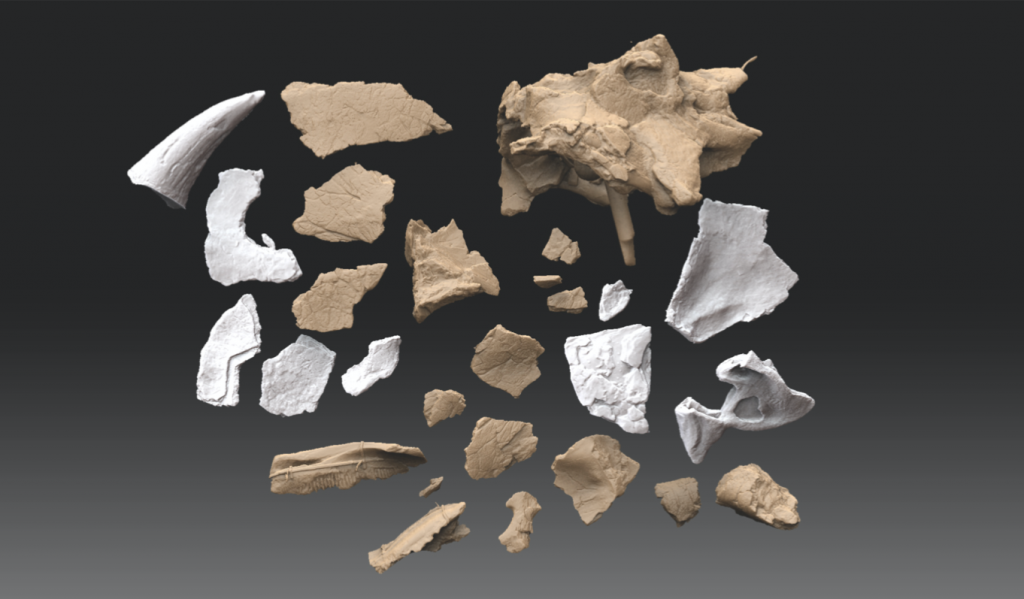

“I demolished it myself,” says restorer Aart Walen, “with Martijn Guliker and Jan Hakhof. Martijn asked me to sandblast the pieces to see which bones were real and which not.” After inventorying this, Guliker made a kind of blueprint of which piece belonged where by numbering the bone fragments. Then the work stopped for a while because the Dinolab had to process the findings of a Naturalis team in America. The most exciting dinosaur excavations ever, according to the researchers involved.

Meanwhile, Science Centre Director Michael van der Meer saw the new acquisitions of Naturalis as an opportunity to bring Skull 21 back to Delft. Reconstructed using the best digital tools: 3D scanning, 3D modelling and 3D printing. The 21st century museum piece not only had to be an impressive historical piece, but also a showpiece of what digital 3D technology is capable of today. It had to be a marriage between palaeontology and 3D technology, between bone builders and model makers, between craft and data. That is what Skull 21 now stands for: an example of how knowledge and technology can resurrect a long extinct animal from bones and plastic.

Form finding

The reconstruction was a collaboration between restorer Aart Walen and 3D model maker Javid Jooshesh from Rotterdam. “We had to get used to each other’s approach in the beginning,” said 3D specialist Jooshesh. “While Aart was cleaning and sorting out the bones, I was working on 3D scans of the bones that I was putting together with the computer as a 3D Tetris.” The first step was to find out how Kruizinga had reconstructed the skull, no matter how mistaken it was.

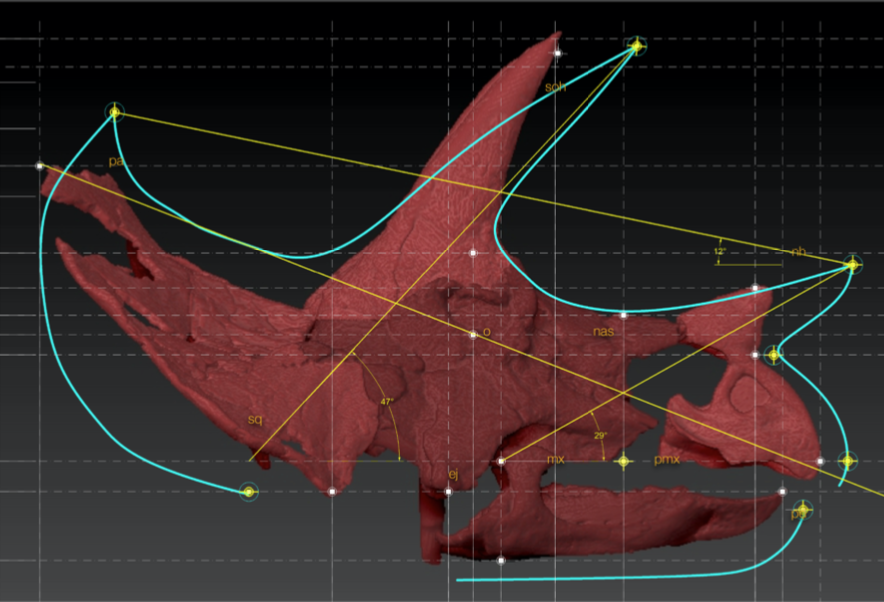

But what was the right shape? Jooshesh studied two smaller but comparable and fairly complete skulls from collections in Yale and Munich. He made optical 3D scans of them. “The scanner reads two million points per second, that’s very precise. In the end, you have a detailed spatial model with a resolution of 0.3 millimetres.”

In consultation with Naturalis’ Dinolab, Jooshesh determined about 10 points on the skull between which he measured the distances and calculated the proportions of those distances. The TU Delft skull turned out to have strange proportions compared to those from Yale and Munich. The horns were 20 degrees too far up, the dorsal shield was too small and the snout too short. Jooshesh then adapted the 3D model of Skull 21 to the dimensions of the other two.

Jooshesh collected 1,000 detailed shots of fossil bone structures as a basis for the surface structure of the 3D printed parts

He still had to fill in missing parts – almost half the skull at TU Delft. This included facial features such as the horns, lower jaw, bridge of the nose, as well as a large part of the dorsal shield. Jooshesh did this 3D modelling based on the proportions of the other skulls and in consultation with Guliker at the Leiden Dinolab.

“Even then, I wasn’t ready for printing,” Jooshesh says. “Because then it would have looked like plastic.” What was missing was the surface structure. Bone is not smooth; it is full of fine channels for blood vessels and nerves which branch out in various directions. Jooshesh collected 1,000 detailed shots of fossil bone structures as a basis for the surface structure of the 3D printed parts. “Combined with spatial design, this resulted in a detailed 3D model that was ready for printing and that would fit together like a puzzle,” says Jooshesh. That puzzle is a compromise for the 3D printing technology, which is limited in size to about 50 centimetres. So 3D Printing Prototypes produced parts of the back shield and the horns in several parts.

In the spotlights

In the Science Centre, Skull 21 is the centrepiece of a live presentation, supported by a light show. “These techniques have never been used in a museum before, and certainly not in palaeontology and archaeology,” explains lighting designer Charl Smit. He built the light show that he designed with lighting professor Prof. Dr Sylvia Pont (Faculty IDE) and a team of students. At the entrance, the gigantic silhouette of the dinosaur skull moves over the projection screen surface using five different spotlights, as a guide explains the life of the Triceratops prorsus. Then Skull 21 stands, powerfully resurrected, in the coloured spotlights.

It is only when the spotlights fade and turn to white that the audience sees which parts are original and where the reconstructions are. This light trick is known as spectral tuning - the subtle tuning of LED spectra to the colour of the material, amplifying or eliminating colour differences.

“Our work complements that of Naturalis,” says Science Centre Director Michael van der Meer. “At Naturalis you can see which dinosaurs there were and how they lived. Here we tell the story of the reconstruction of a skull. We show how the techniques have developed since the first reconstruction, and how restorers use them.”