'Innovation does not always have to come from start-ups'

‘That’s impossible’ is the frequent response to the wild ideas of company employees. A pity, says Professor of Entrepreneurial Engineering by Design Frido Smulders.

Start-ups and entrepreneurship are sexy, says the new TU Delft Professor of Entrepreneurial Engineering by Design Frido Smulders. Is this a good subject for a new professor of entrepreneurship? Not for Smulders. He believes that most innovations that are needed to solve social problems should come from existing companies. They are the ones, after all, that have the finances, knowledge and experience. And the people. At least 90% of all TU Delft students work for existing companies after they graduate.

He believes that there is a problem with real radical ideas in companies such as listed companies. These companies are not designed for new ideas and do not encourage entrepreneurship. They often view wild ideas as unfeasible, too expensive and a potential threat to their current products.

Smulders wants to change this. He wants to give teachers the tools to teach their students to operate in entrepreneurial multidisciplinary teams. To design the online courses for this, he will receive starting capital of EUR 50,000 from the 4TU Centre for Engineering Education, an alliance of the four technical universities in the Netherlands.

Why is radical innovation, as you call it, so hard for existing companies?

“It’s because it is hard to take a decision, which is usually based on rational criteria, on what is at that point an irrational idea. Firms are often driven by financing, market share, and the in-house knowledge and expertise. If an unorthodox idea emerges and you don’t know if it fits in your company and if so how, it is simply too left field and is either shot down or ignored.”

Many companies often take over start-ups if they want to be innovative. That is all right, isn’t it?

“That is indeed common practice but the price that companies often have to pay for start-ups is far higher than the costs that they would incur if they would do it themselves. For example, in 2016 Unilever bought the One Dollar Shave Club for USD 1 billion. The usual practice is to buy the company that you want to take over for five to eight times its profit. In this case, it was more than five times the turnover. Let’s assume that it cost about USD 10 million for the One Dollar Shave Club to generate its first clear turnover. Many start-ups fail of course, and in this case you would only have lost USD 10 million. You are now paying USD 1 billion for something that is up and running. If you look at it this way, you can actually fail 99 times for every one success. A large company with a lot of knowledge and resources should be able to do this.”

Why don’t they do this then?

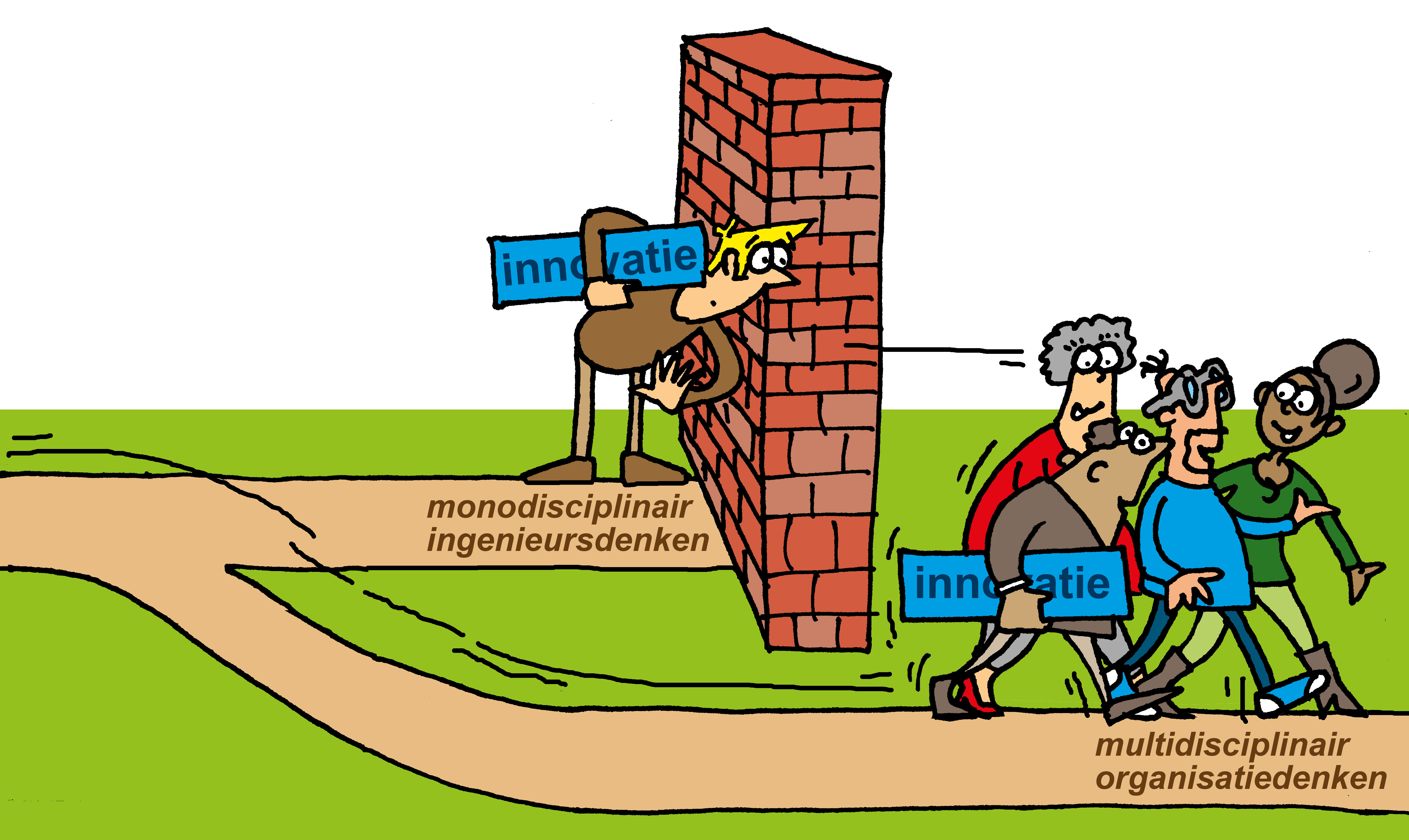

“Companies’ operations are often completely directed at its current products and there is fear of cannibalising them. But in truth, it’s often because the innovation process is little understood. If you really want to collaborate for innovation, you need a multidisciplinary team in which each discipline regularly sticks out its neck to come up with new ideas. And this is challenging. People who come up with different ideas in companies are often put down with arguments such as ‘it will take too long’, ‘it’s too expensive’, ‘it’s impossible’ or ‘he’s at it again’. You therefore make yourself vulnerable if you come up with a wild idea. But in reality, it’s the environment in which you work that has not learned to deal with ideas. This can affect your career in a company. We teach our students to think like monodisciplinary engineers and fall well short in terms of thinking as a multidisciplinary corporation.”

Does that mean that every engineer should think like an entrepreneur?

“No. It’s not about individuals, but teams. You need entrepreneurialism in a team, and the rest of the team members should understand this. Large corporations need it, and this has become clear in the corona crisis. We want to prepare our engineers for this type of unpredictable and uncertain situation so that, if need be, they can innovate quickly in collaboration with many other disciplines. This also implies an attitude of learning along the way instead of fearing making mistakes. You cannot fail if you innovate, you can learn from what does not work.”

How can you teach students this while the education system judges them on their final grades?

“That’s a hard one. I would like to work with my 4TU team on designing a framework which will help teachers to include this in their teaching. This will be the online module. What they will teach as validated knowledge will in fact be the outcomes of the process of a technological innovation. If they can demonstrate how the innovation process was underpinned by entrepreneurship, they will learn from this and will be able to identify the underlying theoretical framework. This may not be the case in every subject. They will go a long way with just one or two subjects in a master’s and we will be able to reach all the engineering students.”