"My interest started during a lecture on load-bearing structures. The lecturer showed all these amazing pictures, but did not explain how they were built." Andrew Borgart has been lecturing at TU Delft for 30 years. Alongside this job, he has been pursuing a PhD since 2009 on a half-forgotten intersection between art and science: the mathematical theory of ‘shell structures’, that is, buildings shaped like shells. "They call me innovative, but actually I'm retro."

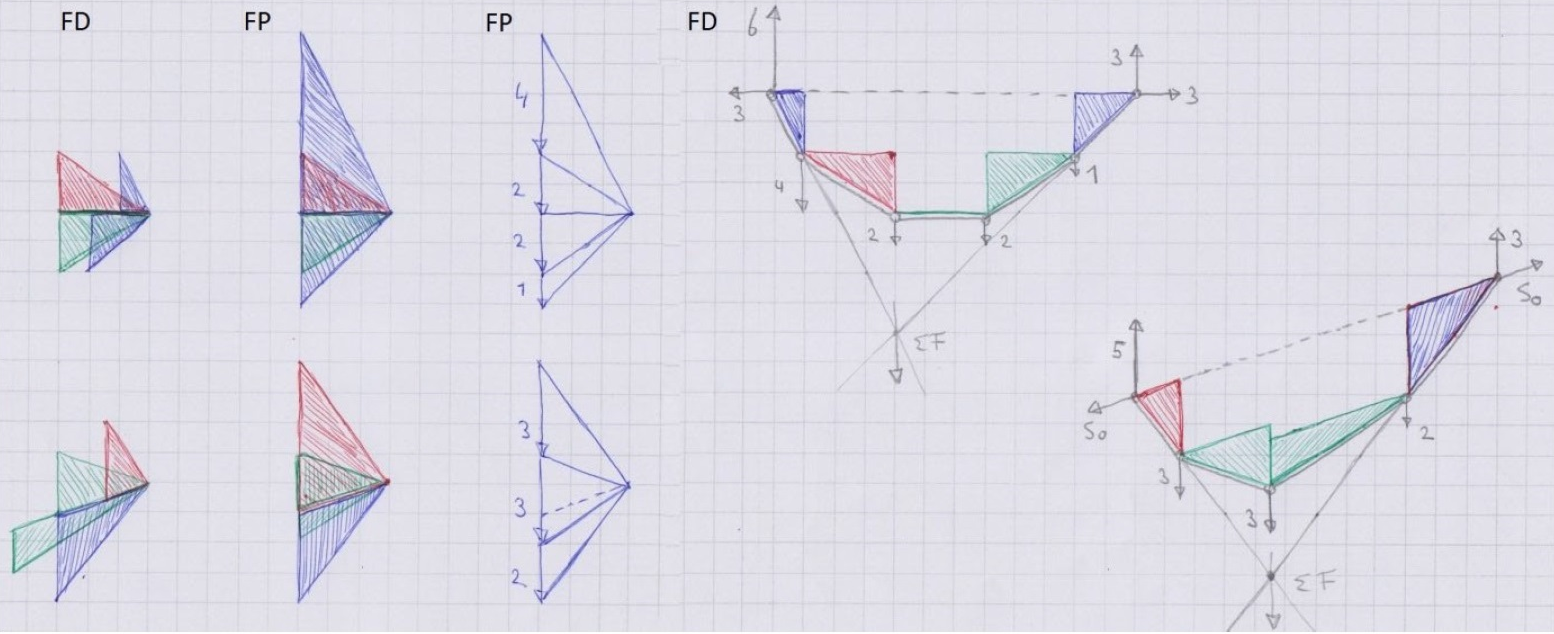

Some people need encouragement or prodding questions to tell their story. Andrew is not one of them. As soon as we are seated on opposite sides of the otherwise empty conference table, he takes off. I frantically write along and only need to interrupt him sporadically to check some detail. And so an extraordinary story unfolds before my eyes. A mixture of science, passion, perseverance, and nostalgia. When he shows me the boxes full of calculations and sketches underpinning his PhD research, I quickly grab my phone to capture the scene.

Perpetual student, perpetual teacher

Andrew's story begins in the 1980s at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy, an art school in Amsterdam. "I dropped physics in high school, so I was not allowed to enrol at Bouwkunde straight away. Ironic, considering I ended up doing such physics-focused research." He loved living among the artistic types, but admits that he did not quite feel at home: "Then again, I was years younger than most of my fellow students." So instead he ended up entering Bouwkunde. At first, that also didn't seem like a perfect fit. Andrew: "I soon got fed up with the endless drawing. All those floor plans... And I considered the lecturers too mild compared to those at Rietveld."

Then came that decisive lecture, where pictures of unusual buildings piqued his interest in mechanics. There, Andrew finally found his niche. ‘I eventually took three years to graduate. Not because it was difficult, but because I liked the subject so much. In the meantime I started teaching, and I never stopped." To his knowledge, he is the only BK student ever to graduate under the Mechanics professor, Beranek: "no one at Bouwkunde specialised in Mechanics." Subsequently, Andrew, his colleague Gerry, and professor Beranek formed the research group ‘Krachtswerking in gebouwen’ (Mechanical Forces in Buildings). But over time, Andrew became the only one left. Eventually, this one-man group merged with that of Professor Mauro Overend.

Translating forgotten skills

In the years after the Bouwkunde-fire, when Andrew was working from CiTG, he started conducting research in earnest into the theory of shell structures. These extraordinary constructions are characterised by large surfaces of thin matter, which only works if their shape is precisely calculated to support the weight. Andrew: ‘’The required mathematics was quite advanced in the 1950s, but a lot of knowledge has been lost since then. Books from that era are hardly legible today and the experts are mostly deceased." There are computer programmes that simulate scale structures, but they have a significant shortcoming: "They only tell you whether a certain design is balanced. You cannot use them to create a new design."

Andrew spent years working with coloured pens, paper, and calculators to untangle this ‘forgotten mathematics’ and transform it into usable computer scripts. As a result, his thesis is full of sketches, which was not always appreciated: ‘People have called it “very unconventional”. I did not receive much useful feedback." But Andrew thinks his research is quite intelligible. "I describe the objects in the language of formulas. If you recognise the patterns, you will naturally understand what I am talking about." In between are computer scripts that you can enter, even with little background knowledge, to design scale structures. “We can once again design structures with a length-to-thickness ratio of 1000/1: dozens of metres wide and only centimetres thick! Such structures are not only aesthetically satisfying, but also resource-efficient and therefore better for the environment."

A shell with a length of dozens of metres and a thickness of mere centimetres is not only beautiful, but also resource-efficient!

Bring back shell structures

Currently, Andrew teaches two undergraduate courses which he makes as interactive as possible. He is also involved with each new generation of students in other ways, for instance through the study association Stylos. Although teaching remains his passion, he sometimes suffers from his relative fame: "I can no longer enter Delft without running into former students. Sometimes I just want to enjoy a beer in the pub in peace and quiet." At least Andrew is satisfied that they no longer have to bother him with the question: ‘When will you finish your PhD research?’ He hopes that his work will contribute to the design of new shell structures. Instead of casting concrete, such structures are now more often made using 3D printers or wooden parts. "That's fine by me, as long as we start building giant shells again!"

Published: June 2024

More information

On 9 July, Andrew Borgart defends his PhD thesis 'The relationship between geometric and mechanical properties of shell structures'.

Read Andrew's complete dissertation.