Demand is high. The shortage of suitable and affordable housing means more and more people are missing out. Is spending ten years churning out new houses and apartment buildings a sensible solution? According to professors Marja Elsinga and Thijs Asselbergs, we do need new buildings, but better use can be made of the existing housing stock, and a critical analysis of the housing system is also needed. Speaking on behalf of an interdisciplinary initiative from the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, in this double interview they call for a substantiated overall vision for the complex housing puzzle.

In February representatives and interest groups from businesses, social organisations and local authorities published an Agenda for Action on Housing. High on the agenda was building one million new homes in ten years’ time. This would mean a considerable acceleration of building production. The election programmes and campaigns of several political parties also present large-scale new building as the solution to the housing shortage and associated problems such as lack of affordability and the complex task of making the housing stock in the Netherlands more sustainable.

Missing out

“Housing has finally become a political priority again.” Marja Elsinga, Professor of Housing Institutions & Governance at TU Delft, reminds us that the building sector was already trying to get the construction of one million new homes by 2030 on the agenda two years ago. “To start with, all was quiet in The Hague until some months ago.” Under the name 1M Homes, two years ago the faculty took the initiative to bring together relevant disciplines to promote substantiated solutions for the housing shortage. “As a collective of academics from a wide range of disciplines in the BK-faculty, we can offer a cohesive perspective for creating suitable housing in pleasant neighbourhoods and districts. 1M Homes is all about creating homes for a large number of people who are missing out at the moment, by building new homes as well as utilising the existing housing stock.”

She gives an example. Why should older people who live alone stay in large, paid-off houses, if living concepts that have fewer square metres but with more facilities and opportunities to socialise offer more comfort? “This would free up large houses for families, or they could be split into multiple units, allowing better housing mobility for different types of households.” The promotion of sufficient housing stock by the government is a fundamental right, emphasises Elsinga. “With 1M Homes, we want to steer towards achieving several values at once. How do you get sufficient housing that is affordable and sustainable and inclusive? The answer is: by a combination of system changes and socially responsible innovation. We are closely monitoring housing innovations and want to help change complex regulations in order to facilitate a more rapid implementation of innovations.”

Housing construction tradition

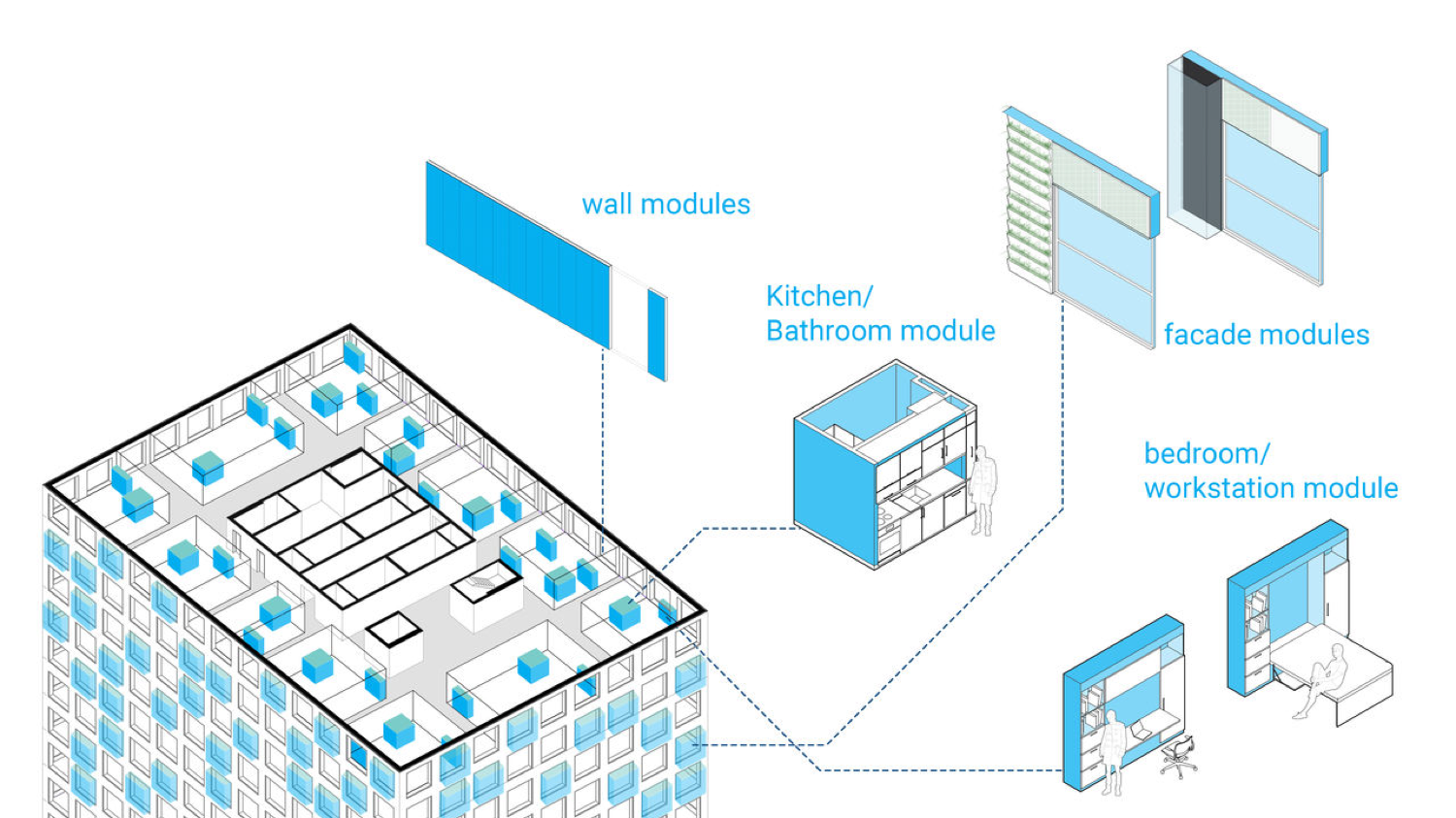

“The cubic metres actually already exist,” says Professor of Architectural Engineering Thijs Asselbergs. He is referring to the amount of real estate that is now vacant or will become so in the coming years. “All kinds of commercial buildings and office blocks, as well as churches and farm buildings can in principle be made suitable for housing use. But making optimum use of these is not so simple under the present system of regulations and conditions. In that respect there is much room for improvement.” For the production of sustainably constructed and utilised homes in which it is relatively easy to switch between living functions, he feels it is necessary to use more open building systems that combine long-lasting basic main structures with a flexible implementation. “We can also adopt far more intelligent ways of using building methods and the life cycle of building materials, for example by focusing on manufacturing components at industrial scale and by making far more use of natural materials.” In his experience, the present generation of students understands this and is learning to design in this way. “For them, new buildings are tomorrow’s renovations.”

If it were up to the two professors, solutions for the housing crisis would be led by such principles: the transformation of existing real estate, involving flexible housing forms and the responsible use of raw materials. Asselbergs: “The Amsterdam canal ring has proved to be valuable and sustainable in many ways because it was designed on the basis of multifunctional, renewable building systems.” He also points to the strong housing construction tradition that the Netherlands established in the last century. Much attention was paid to high-quality public housing. “In the past, architects conceived fantastic new housing typologies. And in the same way, we must now be inventive and create adaptable housing in line with the changing society.”

Big picture, long term

Creating living space is primarily a local story. Both professors feel that a municipality, housing association and project developer can use their shared ambitions to achieve the vitally needed innovations in the building sector, but the central government needs to make innovation by builders, developers and investors possible and to simplify the present complex legislation. “Whether we're talking about digitalisation or the energy transition, we need the government to create the preconditions for large-scale innovation”, says Asselbergs. He envisages a far-reaching plan – on the scale of the Dutch Delta Works – for housing, based on clear ambitions. “It's all about setting out the big picture that enables you to guarantee a long-term system change. As an interdisciplinary collective of experts, we can show what can be done and how, by putting forward good, academically substantiated examples.”

Examples that Elsinga gives of centrally driven system changes, are that your social security benefits are no longer cut if you live together with someone, and that investments in a sustainable housing environment with long-term profits are encouraged and profiteering from property management is discouraged. “So that a housing association or an investor has sufficient scope within centralised legislation to work with a municipality to create a great neighbourhood that is accessible to all income groups.” And a municipality can in turn use its land-use policy to encourage initiatives that are good for the city. “Take the housing association for example. When a citizen's initiative needs a loan or a plot of land, the current system treats it in the same way as a commercial investor. But shouldn't a municipality be encouraging attempts by residents to meet their own housing needs?”

All hands on deck

Nationally and locally, there tend to be great differences in more practical perspectives on what constitutes good housing, is Elsinga's experience. During the Parliamentary Inquiry into Housing Associations in 2013, the political parties were initially keen to do away with the system. “But when alderpersons from various municipalities explained the vitally important role that such an association plays in the city, you saw the realisation slowly but surely dawn that reform would be a better option.” What she means to say is that it is important to explain things well to bridge different perspectives and make progress. “Recently TU Delft together with various other Dutch knowledge institutions and many public and private partners submitted a pre-proposal on the housing crisis to the Dutch Research Agenda. This proposal is for a broad study of how the government, the market and civil society at every scale can ensure good and affordable housing in what is in many aspects a worthy living environment.” It is a case of all hands on deck, warns Asselbergs. “Working from 1M Homes, we are keen to study and explain how more living space can relate to the necessities of life of a wide range of users and to affordability, adaptability, less environmental burden and more pleasant neighbourhoods.”

Published: May 2021

Header photo: Wiki homes in Almere: an example of industrial, affordable, energy-efficient and customised for residents (photo by Maarten Feenstra)

More information

Marja Elsinga