The Delft Tree Atlas: much more than maps

Did you know that many cities are also forests? You can see for yourself when you switch Google Maps to satellite mode. From this bird’s-eye view, you will notice that the average tree cover in cities often exceeds 40%, well above the lower limit of the ‘forest’ classification. Certain regions of Delft even reach 65%, which is more than most natural forests in Europe. But what kind of forest is Delft? Or, more accurately, which kinds? Just one of the many questions examined in the Delft Tree Atlas.

“We can broadly divide our sources into three categories.” René van der Velde is one of the main driving forces behind the Atlas. He is associate professor in Landscape Architecture and Urban Forestry at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment. “Firstly, historical analysis: maps, inventories, postcards, paintings, travel logs, and any other archival footage we could find. Secondly, spatial analysis: our baseline information came from Delft’s well-maintained public tree database. But we also performed lots of fieldwork to study the distribution of trees and distinguish tree formations. And thirdly, dialogues. For example, between ecologists and landscape architects walking along predetermined routes through the city. But we also collaborated with an artist who held an imaginary dialogue with the city of Delft as a conversation partner.”

Historical archives were a major source of both information and inspiration.

The contents of the Delft Tree Atlas

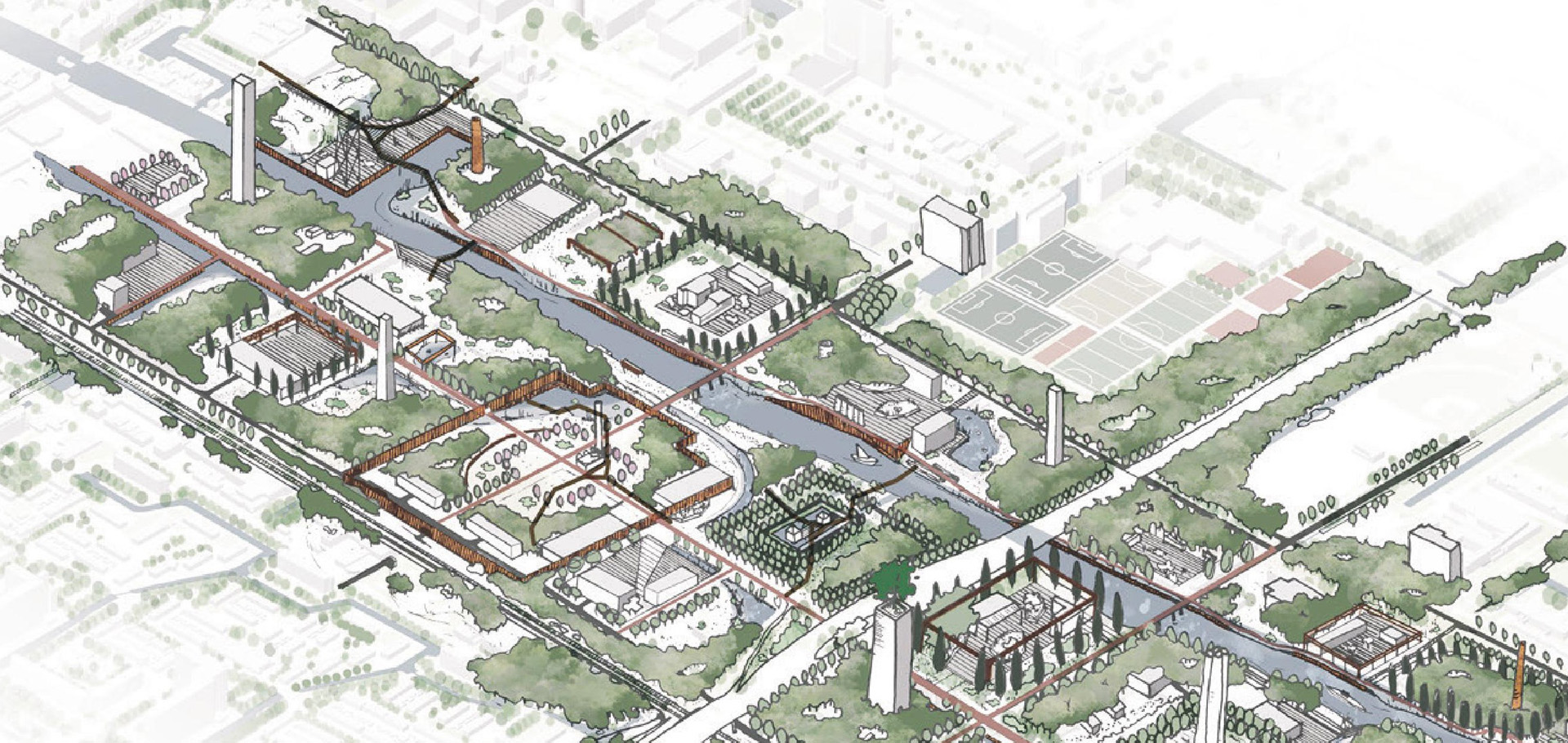

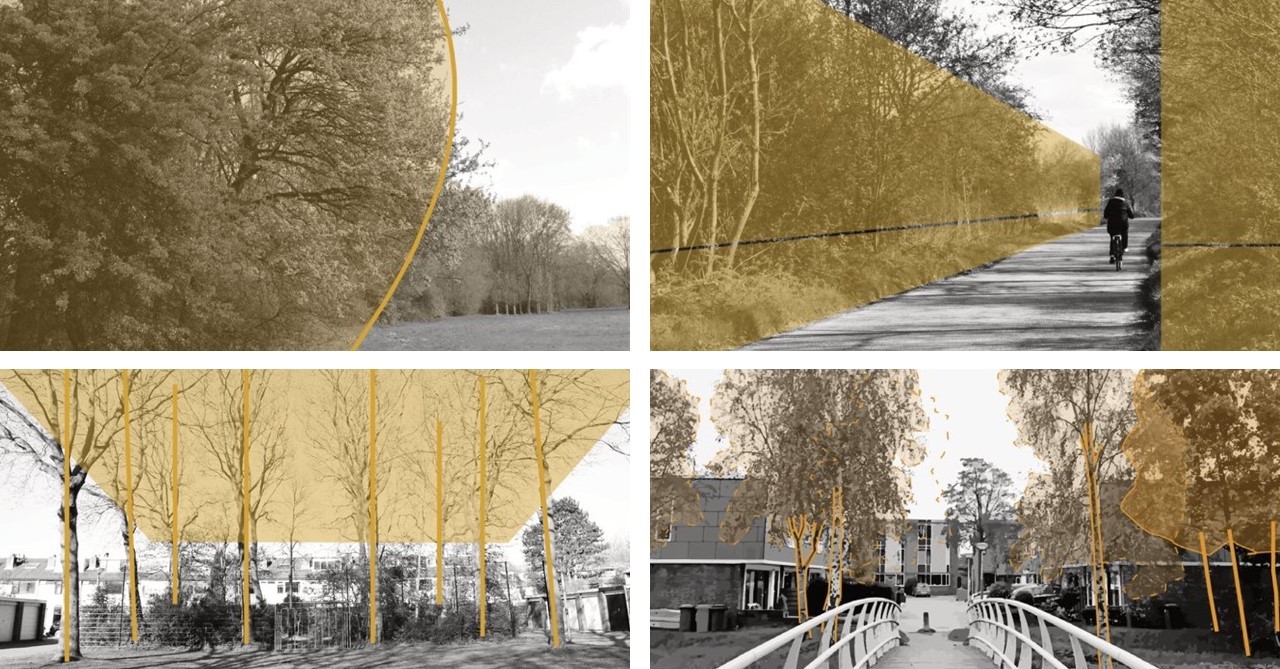

The Atlas is the culmination of years of work by researchers, students, architects, municipal officials, and an artist. As such, its contents cannot be summarized. Instead, here are some examples. In the Atlas you can find Maps of Delft and its surroundings showing the historical development of trees with their associated ‘forest types’. The maps span the period between the 16th and 21st centuries. Also, a ‘grammatical system’ of tree distribution was designed to allow detailed discussion of the urban forest. And a thorough analysis of the entire tree population of Delft, resulting in a reading of the city as a mosaic of eight different urban forest types. The Atlas also contains illustrated essays discussing the changing role of trees in urban landscapes. And finally, you can find experimental proposals to transform the Prinses Beatrixlaan (currently a major traffic artery) and a section of the Schie-oever (a former industrial zone) into tree-rich landscapes.

The Schie-oever reimagined as an Urban Forest, a combination of nature and residential areas. This design is part of a larger project of Jan Houweling, one of the graduate students from the Urban Forestry studio.

The purposes of the Delft Tree Atlas

Since it contains such a multitude of projects, the Atlas is meant to serve many purposes. René: “The historical sections offer an alternative way of looking at the development of Delft. Meanwhile, analyses of the current situation showcase the multitude of ways in which trees shape and interact with their urban surroundings, and how this can serve as a basis for new urban development. And of course, the Atlas draws attention to the advantages of urban forests in climate adaption and resilience.” So, who will use the Atlas? “Urban planners and landscape architects can use it to better ‘weave’ trees into policies and designs. And for citizens, the Atlas offers a guide to experiencing the aesthetic and functional value of urban trees. Ultimately, our aim is to trigger a paradigm shift in how we all see the connection between city and nature.”

Four examples of the many tree formations identified in the Atlas. Clockwise from upper left: Pillow, Screen, Curtain, and Orchard.

More information

The first official version of the Delft Tree Atlas will be presented at a mini-symposium on 5 October at 15:00. The event will take place in the Berlage rooms at the faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment and is open to all.

The core of the Tree Atlas project consists of three researchers: associate professor René van der Velde (Faculty of Architecture and the Build Environment, TU Delft), assistant professor Saskia de Wit (Faculty of Architecture and the Build Environment, TU Delft), and professor emeritus Erik de Jong (UvA). These researchers were over the years supported by MSc students from the Urban Forest Places track (Faculty of Architecture and the Build Environment, TU Delft): Roberto Wijntje, Machteld Zinsmeister, Emma Kannekens, Jianing Liu in 2020, and Ioanna Kokkona, Lotte Oppenhuis, Jan Houweling, Floris Beijer, Willemijn Schreur in 2021.